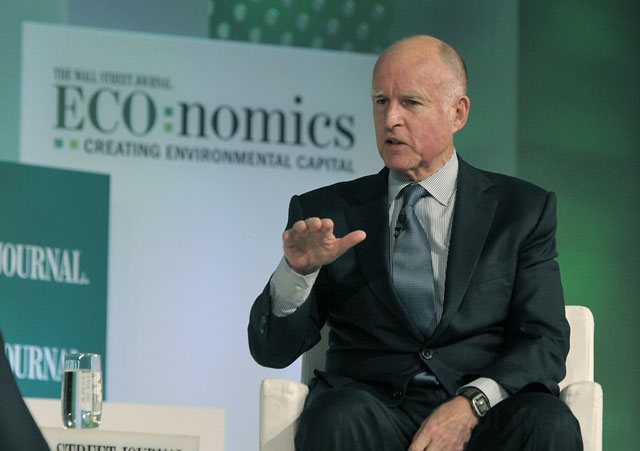

Jerry Brown on California’s Past, Present, and Future

Governor Gives Friday Keynote During ECO:nomics Conference at Bacara

“I want to deal with stuff,” said Governor Jerry Brown on Friday morning at the Bacara in Goleta in the middle of his keynote conversation with the Wall Street Journal’s Robert Thompson during that newspaper’s annual ECO:nomics conference. “You’ve got to try many paths because a lot of them don’t work. I’m open, I’m curious, and I like to try new things.”

Characteristically no-nonsense, blunt, and engaging, Brown’s lively 45-minute talk covered a range of topics, from past mistakes and this November’s tax ballot proposal to fracking, the Solyndra scandal, opening up trade with China, and keeping California as a major oil producer. In an age of politicians who are afraid to say much of anything for fear of scaring possible voters, Brown’s candid commentary was refreshing and even inspirational at times, with one audience member proclaiming that he was by far the best speaker yet at ECO:nomics 2012.

The talk began with a look at the evolution of the California economy from when Brown was first governor — the youngest of the 20th century, apparently — to today, when he’s the oldest governor in the 21st century. When he was first elected in 1974, Brown had a $6 billion surplus on a $44 billion budget. When elected in 2010, he came into a $26 billion deficit on a $90 billion budget. “That was the mess I inherited,” said Brown, quickly adding with a smile, “By the way, every governor inherits a mess.”

Explaining that California has always been a leader in renewable resources — in fact, the state had more than 90 percent of the wind energy on the planet until the oil market crashed and gas got cheap in the 1980s — Brown praised policies on greenhouse gases and efficiency standards, claiming that they’ve created lots of jobs and saved the state $50 billion. “And we set the pace for the nation,” said Brown.

Then Brown slipped into a bit more reflective mood. “I’m more skeptical of everything — I’m skeptical of even my own ideas,” he said, of his intellectual growth over the decades. “Just looking at stuff, shit happens.”

That list could certainly include nuclear power, which Brown touted as “good for greenhouse gases and pretty reliable.” He said that nuclear does have issues, but that he was “open to it. I want to make stuff work. I want to deal with climate change.” He further explained, “Nuclear is a serious technology that serious people need to think about, and I definitely include myself in that group.”

When Thompson quoted a poem from the state’s first Latino poet laureate, Juan Felipe Herrera, whom Brown recently anointed, the governor dispelled the idea that he lives without boundaries. “Life without boundaries? I think the key is boundaries,” he explained. “Imagination doesn’t have boundaries, but if all you have is imagination, that’s akin to insanity.”

Brown wasn’t yet prepared to give his thoughts about fracking — the newer type of oil extraction that some say could pollute groundwater — but said he had asked an expert who told him that “it’s not as bad as the environmentalists say and not as safe as the oil companies say.” Brown did pledge to keep California as an oil boom zone. “California is the fourth largest oil producing state, and we want to continue that,” said Brown, who added he has drastically increased permitting for new oil development.

Brown’s conversation was billed as a discussion over whether California’s heavy regulations are bad for business, and Thompson lobbed that question at Brown head on. “No,” said Brown flatly, explaining that a report from the early 1970s said that the state was the worst for business back then. “But since that time, our gross domestic product went from $350 billion to $2 trillion.”

Brown admitted that the state’s regulations can be difficult and challenging, but that the state economy continues to excel. “There’s a lot of money sloshing around California,” said Brown, “and there are a lot of people who are getting their share of it.” He said that the state continues to foster a very “yeasty and creative” environment amidst increasing regulations and that he just tries to “herd the cats.”

When asked about his legacy, Brown replied, “I don’t think people remember governors that much.” But he said that he plans to reduce California’s prison complex, that he’s working on establishing a more reliable water supply, that he’s interested in pursuing the high-speed rail project, and that he’s working on pension reform. “I’ve got a lot of ideas here and I’m working on them,” said Brown, later laughing, “A legacy makes it sound like you’re going to go away? … I just enjoy being here.”

Toward the end of his talk, Brown explained that he thinks “a government can best solve those problems that it itself first created,” that he thought the Solyndra scandal amounted to “chump change” compared to the nation’s financial breakdown, and that it’s hard to be a politician like him due to 24-hour news cycles, multimillion dollar campaigns, and the need to quickly get up to speed on industry innovations like fracking.

Altogether, Brown said that everyone should expect failures to happen, and that’s not a horrible thing. In fact, Brown explained, “I think we can learn a helluva lot more from our mistakes than from our successes.” The crowd of industry titans and leading environmentalists applauded in unison.