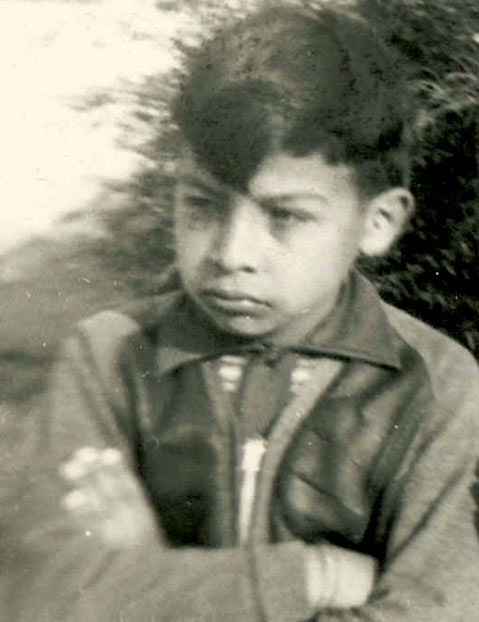

Alberto Paul Pizano’s Life

Alberto Paul Pizano, American of Mexican Descent

I am an American of Mexican descent, born in East Los Angeles, the sixth child of Mexican immigrants who came to the United States in the second decade of the 20th century. Spanish was the language I spoke until kindergarten, where I was first confronted by English, and where I learned that outside my immediate community, I was considered a foreigner, not entirely an American.

There was always that subtle apprehension toward me on the part of non-Latinos. In extreme cases, there was outright hate; in others, the condescension was palpable and pervasive. Once, during school Open House, in an effort to be respectful, I responded to a female teacher by saying, “Yes, sir.” She looked at me for a moment, bewildered and amused, then sneeringly complimented my mother on her children’s courteous behavior. The jeers and laughter from schoolmates, then and for months after, still resonate in my mind’s memory board.

In the classroom, at Hammel Street Elementary School, I still remember, after some 70 years, Mrs. Schaeffer describing how soldiers at Valley Forge “left bloody footprints on the snow.” I listened, enraptured, to the story of an American patriot who regretted that he had but one life to give for his country. I imagined a turbulent sea, the battered Bonhomme Richard — and Captain John Paul Jones, in the face of disaster, refusing to surrender to the British fleet. I dreamed of pioneers crossing mountains, rivers, and plains. I imagined myself a slave in the Old South, and also as the gallant Southern cavalier, an owner of human beings, who, enlightened or tormented, freed his slaves. In my heavily accented voice, I sang to the memory of Old Black Joe and to the mournful refrains of “Dixie” (Mrs. Blodgett, our music teacher, must have been a Southerner). I memorized and proudly recited the Preamble to the Constitution and the Gettysburg Address. I believed in the magic that was America — I was an American.

At home, my father celebrated Cinco de Mayo and the 16th of September, Mexico’s Independence Day. He proudly recounted the bravery of Cuauhtémoc, the Aztec prince, who, rather than reveal the location of the fabled Aztec gold, withstood the burning of his feet; of the priest Miguel Hidalgo, who proclaimed Mexico’s independence with the famous grito; and of Los Niños Heroés, the boy heroes who died defending the Castle at Chapultepec against the invading American forces during the Mexican-American War. My father vowed, time and again, to return to his Mexican homeland. “¡Mi tierra, mi tierra!” he would cry. He never returned.

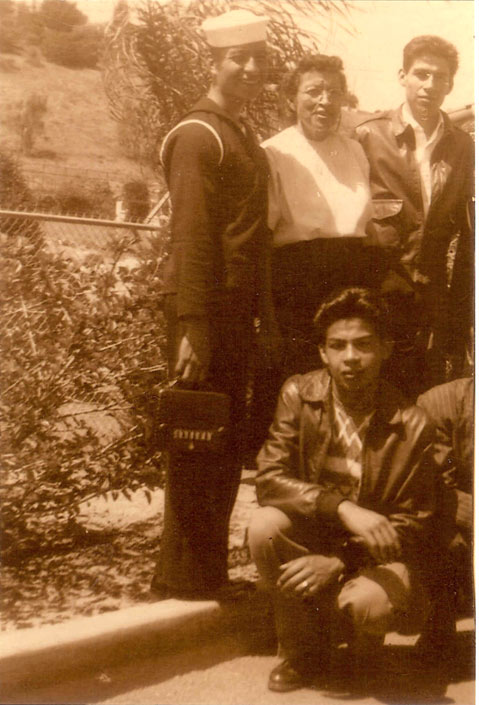

Then the contradictions of his existence would erupt with a frightening force, and he would praise president Franklin D. Roosevelt for having kept his family from hunger, for giving him a WPA job building the Arroyo Seco Parkway; and for the opportunities he felt his children would have. He proudly sent his sons to the military. But he died, broken in spirit, a janitor at a bank. When I went there to pick up his belongings, his supervisor, with a blank expression, said, “He was always a clean man.” Nothing else. Somewhere deep inside of me, young as I was, I felt the social and emotional contradictions my father must have felt — the soul of my heritage confronting the reality of America.

Yes, I am an American, not unlike the descendents of immigrants from Europe (except that I was born in my ancestral lands). The color of my skin made it more difficult to be a “real” American. But the sweep of demographic history, the force of the U.S. Constitution, and an awakened human decency that asserted itself during the turmoil of the 1960s have given me and all Latinos a place at the table, a slice of the American pie, and may well put Latinos in a position where they will play a major role in determining the course of America’s destiny. The salt of Dandi is in our hands — not symbolic of casting off foreign oppression, as it was for Gandhi in India, but of the freedom Latinos seek, despite continuing obstacles, to fully pursue Thomas Jefferson’s promise of happiness in America, a land that is, and has always been, firmly and irrevocably, “mi tierra.”