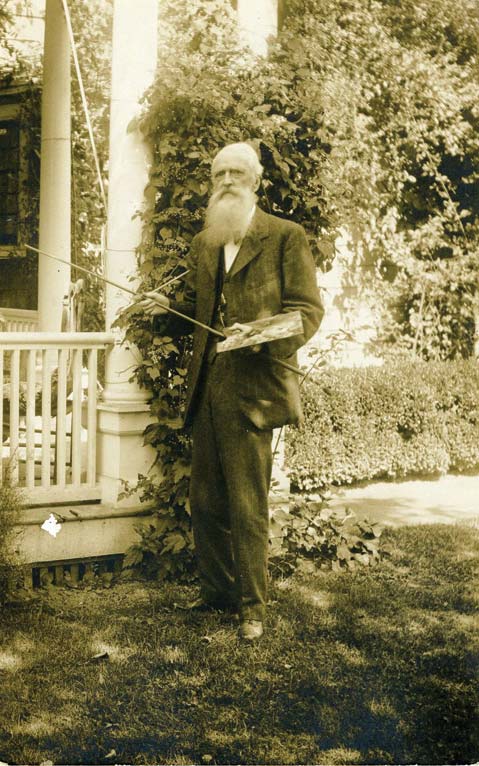

Artist Thomas Moran

America’s Romantic Landscape Painter

Thomas Moran has been called “the last of America’s romantic landscape painters.” In the early 1920s, he and his daughter, Ruth, settled here — a major addition to the area art colony. By the time of his death in Santa Barbara in 1926, Moran was known as the “dean of American artists.”

He was born in England in 1837. His parents were weavers in the textile industry, displaced by the advancements of the Industrial Revolution. When Moran was 7, the family immigrated to the U.S., and Thomas was apprenticed to a Philadelphia engraver. As a teenager, he began executing landscapes in oil, and, by the time he married in 1863, he was making a respectable living as a painter and illustrator.

In 1871, Moran joined the U.S. Geological and Geographical Survey expedition, tasked to survey portions of the Montana Territory, including what is today Yellowstone National Park. Moran received $500 from Scribner’s Monthly and $500 from the Northern Pacific Railroad for drawings of the region. Even though he had never ridden a horse before, he overcame his discomfort by tying a pillow to his saddle.

Moran was mesmerized by Yellowstone Canyon and returned with his luggage brimming with sketches. Moran’s work, along with the photographs of William Henry Jackson, another member of the expedition, inspired Congress to set aside Yellowstone as the first national park early in 1872. Moran’s oil “Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone,” which took six years to complete, was hailed a masterpiece, and the federal government paid $10,000 for the 7-by-12-foot work. It was the first landscape to be displayed in the Capitol. His reputation was made, and he came to be known as Thomas “Yellowstone” Moran; he often signed canvases with the initials, TYM.

Moran conducted a series of trips throughout the American West. In 1873 he accompanied naturalist John Wesley Powell to Little Zion Valley (now Zion National Park) and the Grand Canyon. The latter stop resulted in another epic canvas, this also purchased for $10,000 to hang in the halls of Congress. Over the next four decades, Moran made trips to the Grand Tetons, the Snake River Canyon, New Mexico, Colorado, Nevada, and Florida, as well as Mexico, Scotland, and Italy. In 1884, he was made a member of the prestigious National Academy of Design. A prodigious worker, he produced more than 1,200 oils and innumerable sketches, drawings, watercolors, etchings, and other works.

In the early 1900s, he began to draw more upon European themes, in part as a response to the change in public taste, while remaining true to his style. He had nothing but contempt for the modernistic, more abstract styles, which characterized the cutting edge of art in the early 20th century.

After his wife’s death in 1899, Moran was accompanied in his travels by his daughter, Ruth. They began to spend winters in California in 1915, first in Pasadena, then here. Moran made a final trek to Yellowstone at age 87 and continued to work steadily until his final illness. His work was neglected for decades, but today his canvases are viewed with renewed respect — a reminder of the “beautiful and glorious scenery with which nature has so lavishly endowed our land.”