James Turrell: A Retrospective

Unique Artist Gets a Year of Retrospectives Beginning Now at LACMA

The year 2013 is looking to be the year of James Turrell. This LACMA retrospective, which opened Memorial Day weekend, is truly enormous. There are nearly 50 works occupying 33,000 square feet of gallery space — the entire second floor of the museum’s Broad Contemporary building and a third of its Resnick Pavilion. As the biggest and first of six concurrent, separately curated exhibitions about to open — Turrell’s work will also be at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, June 9-September 22; the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, June 21-September 25; plus three more locations — LACMA’s show anchors a sort of national retrospective of the artist’s five-decade career. If it seems that, more than almost any artist except perhaps Christo, Turrell’s work consistently requires these leagues of real estate, that’s because it is about space itself; Turrell creates carefully controlled light effects that explore how we experience the dimensional world. At LACMA, although several of the exhibition rooms are taken up with fairly conventional small objects such as prints, holograms, photographs, and scale models, the main events are these giant light spaces. Where in a typical Turrell exhibit the viewer might encounter one such work, at LACMA right now there are 10 of them, each requiring an entire room of its own and some of them filling spaces as big as theaters.

Turrell became interested in perception as part of a group of L.A. artists dubbed the Light and Space movement, which centered on the Santa Monica neighborhood of Ocean Park. There, in 1966, Turrell rented the Mendota Hotel and began experimenting with sunlight. By painting over windows, then opening apertures in the building’s skin to allow selections of outside light to enter the room, Turrell created works of art that changed radically depending on the time of day and the passage of day and night. From there, he went on to discover various techniques to “materialize” light: projecting it to create the perception of depth and volume appearing where there is no actual space. The LACMA retrospective is particularly strong in the area and has several elegant examples from the period, including the following: “Afrum (White)” from 1966, in which light causes a cube to appear to extend from a wall, and “Juke, Green” (1968), where light seems to pour into an open window where there is really just a bare surface.

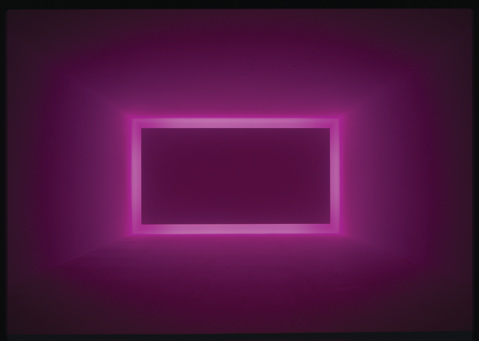

Next Turrell tackled the problem of creating the appearance of flatness where there is depth, such as in his famous Skyspaces, which use cutouts in roofs to frame sky, flattening its depth into seeming planes. Although there are no Skyspaces in the LACMA show, one room is devoted to pictures of and plans for the more than 75 of these works that he has made all over the world. The three most impressive works in the show are “Key Lime,” “Wide Glass,” and “St. Elmo’s Breath.” Each of them takes up an entire eerie room where one is challenged to tell whether a flat surface is actually an open space or whether a deep room is, in fact, a flat surface.

Inside Turrell’s light-driven conundrums, the competing senses of confusion and evolving awareness are exhilarating. The color and intensity of the light continuously change in ways that are in some ways subtly manipulated by the artist and in others produced by our own brains. It is often hard to tell which, and this is the point — with Turrell, uncertainty illuminates perception. The artist has explained his work thus: “We all know the sky is blue, but it’s blue because we give it its blueness. We all have prejudiced perception, or perception that we’ve learned. And I like to push that a bit.”

At LACMA, several of the works are designed to be seen by only a few people at a time, and staff members limit the number allowed inside. “Breathing Light,” a species of what the artist calls a Ganzfeld, accommodates only four people at a time, but once in, one can stay for as long as one likes. My advice is to take your time. The longer you attend to “Breathing Light,” the more the seemingly flat field of color before you subtly gathers depth and, gradually, the more the boundaries between it and the rest of the room begin to blur, flicker, and who knows what else. As in a drug experience, you dose yourself with a Turrell piece, and then you wait for it to come on, marveling as odd things happen in your mind. Surely this kind of art is the height of solipsism — and yet it is, paradoxically, a solipsism of awareness rather than intoxication. It’s a kind of practice, not unlike meditation, that promises to reconnect us to the world by making us aware of how we experience it. In so doing, we shape it anew.