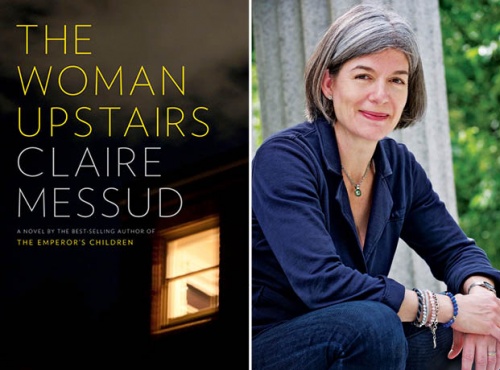

Review: The Woman Upstairs

Claire Messud’s New Novel Takes on a Surprising Perspective

Any potential reader who learns that the plot of Claire Messud’s new novel revolves around a third-grade teacher who takes an unhealthy interest in one of her students and his parents could hardly be blamed for taking a pass. Yet the story, told by the teacher, Nora Eldridge, is often riveting, in large measure because it reveals a perspective that’s rarely spotlighted — in fiction, or in life — that of “the woman upstairs.” “We’re the quiet woman who lives at the end of the third-floor hallway, whose trash is always tidy, who smiles brightly in the stairwell with a cheerful greeting, and who, from behind closed doors, never makes a sound,” Nora writes. “We’re completely invisible,” she concludes, before launching into an almost revolutionary pronouncement: “The question now is how to work it, how to use that invisibility, to make it burn.”

When the book begins, Nora is 37 and single, living in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She finds some pleasure in teaching her students, but she mostly dreads the encounters with her aging father and aunt. Her friend Didi is supportive, but happily paired up with another woman. Having given up her dream of being an artist, Nora is drifting through an uneventful life.

Then her favorite student, Reza Shahid is bullied. His radiance dimmed, Nora feels she must make personal amends to the boy’s father, Skandar, a Lebanese professor teaching at Harvard, and his Italian wife, Sirena, a conceptual artist on the verge of breaking big. Nora’s affection spreads from Reza to his parents, and she is quickly caught up in their glamorous lives.

Suddenly alive with possibility, Nora co-leases a studio with Sirena, finally returning to her art. Of course in keeping with their personalities, Sirena’s project is big and bold: An avant-garde recreation of Alice’s Wonderland. Nora, by contrast, begins building dollhouses. (Ibsen’s Nora Helmer, heroine of A Doll’s House, is surely being evoked here.) For much of the novel, Nora works on a precise miniature recreation of Emily Dickinson’s bedroom. Dickinson is in some ways an appropriate model for an artistically ambitious woman living a closeted life, yet Nora lacks her boldness of spirit, a quality far more in evidence in Sirena’s life and work.

Unfortunately, the novel’s ending is anti-climactic. Sirena’s betrayal is casually mean-spirited, but Nora finds out about it long after the two have ceased to be friends, and it doesn’t seem to merit the great rage described in the opening chapter. Moreover, Nora’s revenge, writing the book we have just read, is hardly a coup de grâce. By her own admission, she’s nearly as much to blame for her unhappiness as the Shahids.

Still, her startling, if brief, emergence from passivity makes Nora a memorable character. In the throes of her new life Nora writes, “I was suddenly aware, almost in a panic — a joyful panic — of the wealth of possibility out in the world, and also within myself…. I felt all this with the zeal of someone newly wakened — by God, I felt and felt and felt.” Most of us will have experienced a moment like that — and longed to have sustained it, even as we knew how fleeting “the zeal of someone newly wakened” must always be.