Cubist Cowboy

Channing Peake, Pablo Picasso, and Santa Barbara in Modern Art

When Fiesta is over — when the costumes and Coronas have been put away, when the last beach cruiser has made it safely back to Isla Vista, and when all that remains is the confetti still sprinkled on the downtown sidewalks — we reach a natural point in the calendar at which to reflect on who we are as a culture in Santa Barbara and on how we got to be this way. Beyond the broad, popular appeal of Fiesta, Santa Barbara has an ongoing civic attachment to the culture of the great Mission-era ranchos that reflects the complexity, the cosmopolitanism, and even the paradoxical modernity of Santa Barbara’s Hispanic roots.

displayed along the gallery’s outer walls, through a series of freestanding dividers that showcase works by Pablo Picasso.

The Long Reach of the American Riviera

In this season’s most provocative gallery pairing, Peake/Picasso at UCSB’s Art, Design & Architecture (AD&A) Museum puts the longstanding friendship between Santa Ynez rancher/artist Channing Peake and his slightly more famous buddy Pablo Picasso under the microscope. Loaded with outstanding paintings, drawings, and sculpture by both artists, Peake/Picasso — organized by AD&A’s chief curator, Elyse Gonzales, and on view through September 22 — also assembles hundreds of photos, documents, and artifacts detailing Peake’s simultaneous participation in ranch life, the international art world, and the Hollywood celebrity scene of the 1950s and ’60s. By focusing on the friendship, Peake/Picasso offers visitors to the AD&A the opportunity to reconstruct a whole history of Santa Barbara style out of their encounter. This thoroughly researched examination of the Peake-Picasso bromance reveals some unexpected answers to nagging questions about art, machismo, fame, and the elusive goal of authenticity, and it does so in a way that sheds an exceptionally useful light on an important aspect of Santa Barbara’s cultural identity, and one that is often misconstrued. At the back of the catchphrase “American Riviera,” there’s a cultural connection that transcends the coincidences of climate and unites our region with the South of France, Mediterranean Italy, and Spain.

When the young Peake first laid eyes on Santa Barbara as a student at the Santa Barbara School of the Arts back in 1928, the city already presented a fascinating challenge to conventional distinctions between rural and urban, cosmopolitan and provincial. Because, in the words of historian Carey McWilliams, “the rich came first” to this part of the United States; not only did Santa Barbara have a wonderfully solid architectural basis — the kind that can only arise when people who are in a financial position to improve the land directly upon arrival are involved — but it also expressed a high degree of sophistication about the ways in which this improvement was to be done. Everywhere one looked, admixtures of learning and scholarship in relation to earlier architectural and landscape styles were being leavened with an unusual awareness of development at the highest levels of culture. In other words, it didn’t hurt that George Washington Smith, Julia Morgan, and Lockwood de Forest were working here, too.

Key factors in this development of Santa Barbara style, and of Southern California culture more generally, were the extraordinary international treks undertaken by various influential artists and builders in search of the best that the world had to offer in architecture, music, literature, philosophy, and art. For example, Peake was in his twenties when he met George Steedman, the inventor and industrialist who built Montecito’s historical landmark home Casa del Herrero. As a promising student of Ed Borein’s, Peake had learned to draw people and animals with great facility, but it was not until he learned of Steedman’s knowledge of the Spanish Gothic, something Steedman had acquired through extensive travel and research in Spain, that Peake initiated his own lifelong habit of traveling in pursuit of aesthetic education and discovery. What followed for Peake the aspiring artist became an existence twice devoted — once to the people, animals, and land of the Santa Ynez Valley, where he eventually came to be the owner of a substantial working ranch, and then again to these research pilgrimages devoted to finding and learning from the best artists and scholars in the world.

Although the story told in Peake/Picasso begins with one particularly consequential journey — the trip Peake took from Southern California to southern France in 1953 along with his art dealer, Frank Perls — Peake’s travels already had a long history before he ever met Picasso. In the late 1920s, he’d been to Mexico City to observe and learn from the murals being painted there by Diego Rivera, and to the Oaxacan archaeological digs where the precious relics of the pre-Columbian world were excavated. In the early 1930s, a restless, questing Peake traveled throughout the Southwest, much of the time on horseback, sketching and painting the life and art of the Native American tribes of California, New Mexico, and Arizona.

By the mid-’30s, his ambition as an artist led him to New York City, where he took a studio on the West Side and enrolled in the Art Students League. Peake’s New York sojourn brought two important new people into his life: the Italian immigrant artist Federico “Rico” Lebrun, who began as Peake’s teacher and wound up his longtime best friend, and his first wife, the heiress and horsewoman Catherine “Katy” Schott, of New York City and of Santa Barbara. Following their marriage in 1938, the couple acquired Rancho Jabali on 1,600 acres in Santa Ynez Valley, where they would raise four children and thousands of animals, including Driftwood, among the greatest of the early quarter horse studs.

How the Cowboy Met the Cubist

Despite his habit of traveling to learn about art, Peake’s meeting with Picasso would likely never have happened if not for some friends from Los Angeles: art dealer Frank Perls and collectors Sidney and Frances Brody. There are remarkable photos of Peake with both Perls and the Brodys included in the Peake/Picasso exhibit. Perls immigrated to the United States to avoid the war in Europe. After making a start in the art world of New York, he transferred his operations to Los Angeles. In the postwar years, Southern California collectors were buying all the European modernism they could get their hands on and showing it in the marvelous mid-century modern homes that were being built for them by such architects as Richard Neutra and A. Quincy Jones. Perls, whose family had been among Picasso’s earliest dealers in Europe, was in a strong position to bring more new work by Picasso, the world’s best-known artist, to the West Coast. However, even for an insider like Perls, works by Picasso were notoriously difficult to procure, as the artist liked to handle the sales himself and often had to be persuaded in person to let go of something.

On the other hand, by 1951, Perls’s good friends Sidney and Frances Brody already owned a Picasso. In fact, they owned what would eventually become the most expensive Picasso in history, the 1932 painting known as “Nude, Green Leaves and Bust,” which they acquired in 1950 and which Peake saw many times hanging in their spectacular modern house in Holmby Hills. The Brodys paid $17,000 for “Nude, Green Leaves and Bust” when they acquired it from New York dealer Paul Rosenberg in 1950, a fraction of what the picture fetched at auction when their estate was auctioned by Christie’s New York in May 2010 — a cool $106.5 million. This was the milieu in which Peake was active in the early 1950s. On the fateful journey of 1953, as the Brodys pushed on deep into the French Riviera in pursuit of their next acquisition (a highly unusual and totally priceless mosaic by Henri Matisse, who came to L.A. to supervise the installation), Perls and Peake headed to Picasso’s country house, Vallauris.

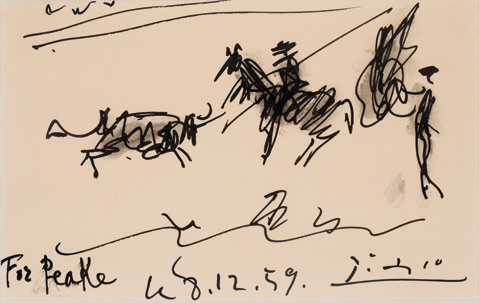

The story of what happened next is well known by now. Perls schemed to win over Picasso with a gift — an original drawing by Rembrandt (!) no less. But it was Peake, not Perls, who charmed Picasso. The master took notice of Peake’s straightforward, hyper-masculine manner and kept staring at his white cowboy hat. Perls, not a little miffed at the way Picasso had virtually ignored the Rembrandt, urged Peake to take the initiative and offer his hat to Picasso to try on. Taking off his white Stetson and letting Picasso try it on became much more than just a great photo opportunity for Peake — it was the beginning of a relationship that would last for decades. It would bring Peake back to Picasso’s studio multiple times and would eventually lead Picasso’s mistress Françoise Gilot and their children to make the journey to Santa Ynez, where they stayed as the Peakes’ guests at Rancho Jabali. The only reason Picasso never visited is because, as a registered Communist, he was not welcome in the United States. For his part, Picasso reciprocated the gesture of Peake’s eventual gift of the cowboy hat, which he left behind with the artist, by giving Peake a small plaster cast of a bull. This simple trade, of a white cowboy hat for a black plaster bull, sealed the deal. Perls got his examples of Picasso’s art, and Peake earned an open invitation to visit Picasso whenever he was in Europe.

Bringing the Cubist Bull Back Home

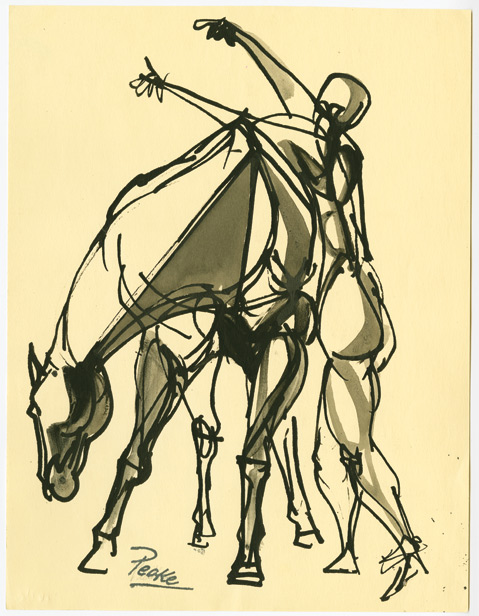

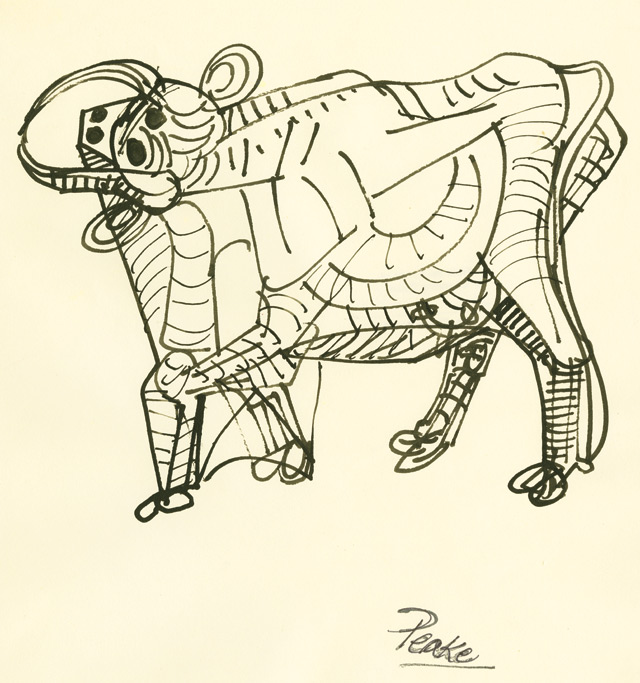

Although he had experimented with modern art techniques before under the influence of Lebrun, this fateful encounter with Picasso, and the gift of the little black bull, drove Peake to explore Picasso’s cubist approach and to share the artist’s grand sense of purpose in more earnest. Never one for leaving things behind, Peake set out in pursuit of cubism without abandoning his primary subject matter, the life of a rancher, which he saw as forming a continuum with his activities as a painter. Like Picasso, Peake was drawn to the energy of life in all its forms. The two men shared what might be called a proprietary interest in vitality, whether it took the shape of a matador and a bull in the ring or of a man and woman in the bedroom. The next phase of Peake’s career as an artist would be its climax, and it would involve the synthesis of multiple strands of influence, ranging from the day-to-day life on the ranch to the existential drama of the bullring and beyond.

Picasso’s style of fragmentation and multiple perspectives.

Picasso had long harbored an interest in cowboys and the American West. Like many Europeans of his era, he devoured not only the Hollywood films of William Wyler and Howard Hawks but also the Western adventure novels of Zane Grey and others as they were translated into French and Spanish. The Spanish vaqueros had conquered Latin America through superior horsemanship, and pride in his Spanish heritage colored Picasso’s view of animals of all kinds, including of course the bull, which became his personal symbol in the years leading up to World War II. While Picasso participated in the great modernist fascination with the bullfight, he was disdainful of what he saw as Ernest Hemingway’s exploitation of the Spanish culture, and he called him out on several occasions for playing the aficionado with too much enthusiasm and not enough authenticity.

Authenticity was Peake’s strong suit. As the founding president of the Pacific Coast Quarter Horse Association and a champion roper, Peake possessed a knowledge of bulls that was firsthand rather than acquired secondhand through spectating at bullfights. Peake was familiar with the ambitions of the great modernist artists to achieve something monumental, as can be seen in his murals for the airport, the library, and El Paseo, among others. Like Picasso, Peake served a long apprenticeship in figure drawing before he began to explore the cubist approach to flatness and space. The two men passed many hours together in competitive sketching, comparing and even trading their drawings of horses, bullfighters, rodeos, and bulls.

But Peake was an astute reader of paintings, and he knew that Picasso’s imagery did not stop with animals or with the direct, uninflected representation of nature. Beyond the analytic cubism of Picasso’s early innovations lay the extreme visions of his middle years, and these were the pictures Peake is most likely to have seen when he visited. Grotesque, elongated figures of women with gnashing teeth, their mouths twisted sideways, their limbs spread open in impossible positions, populated many of Picasso’s works from 1928 on. These crazed-looking bathers and scary biomorphic monsters must have haunted Peake, who was driven by many of the same desires as Picasso to seek satisfaction beyond the boundaries of representational art and of marriage.

Attack of the Farm Machines

Meeting Picasso and seeing his work drove Peake to reconsider the subjects of his paintings, and while he continued to paint and draw the cows, horses, and people around him, Peake made his commercial breakthrough as a modern artist with a series of cubist paintings depicting the machinery on his farm. These large and daring experimental canvases, filled with Picasso-like distortions of thrashers, tillers, and other farm implements, became Peake’s signature oeuvre. First shown at the Frank Perls Gallery in Beverly Hills, the farm-machine images created something of a sensation and were eventually shown alongside the machines themselves in a famous show at the San Luis Obispo Museum of Art in 1957. These were the glory years for Peake. Like Picasso, who once fashioned a bull sculpture out of the discarded saddle and handlebars of a bicycle, Peake could appreciate the biomorphism of these machines, and he was steeped in the rhetoric of the image that allowed Picasso and the surrealists to combine widely disparate subjects, such as the savage masks in Picasso’s famous “Les Demoiselles D’Avignon.”

Why did Peake choose farm machines as the subject matter for his cubist breakthrough? There are several explanations. Patty Look Lewis, a distinguished Santa Barbara painter who knew Peake and once represented his work in her gallery, sees him as “a natural when it came to taking what was in front of him without hesitation.” In this view, Peake would have made something out of the stuff in front of him on the ranch no matter what. But a second explanation perhaps does more justice to the artist’s depth of understanding, even if it can’t be proved without Peake himself being available to confirm or deny it.

When Channing and Katy Peake bought Rancho Jabali in 1940, ranching was well on its way to becoming a residual formation in California’s economic history, not only as a symbol of the lost Spanish colonial past, but also as the victim of development. In most places in the state, this way of life was bound to give way to either suburban tract housing closer to the coast or industrial agriculture farther inland. These farm machines that Peake was painting would eventually render his beloved animal-powered version of ranch and farm life obsolete.

In choosing these objects and the cubist method, Peake went against the conservative grain of the Western aesthetic. “Imagine the atmosphere at these brandings,” says Lewis, who was brought up on one of the ranches. “The cowboys were not interested in what was happening in the Paris art scene.” But Peake could handle himself and a horse, so he was fully functional in these other forms of competitive masculinity, as well. Like his beloved Santa Barbara, Peake was never fully rural in any cultural sense. There was an irreducible cosmopolitanism to his ranch life that remains a remarkable feature of the area today. The Peakes became important horse breeders, but that didn’t stop them from traveling the world and collecting friends and art in all kinds of places.

¿ Quién Es Más Macho, Picasso o Peak ?

From all the many highly detailed accounts of his life now available, Picasso would seem to have thrived on complex relationships steeped in a variety of competitive masculinities, starting with art but extending through to such pastimes as the bullfight and his sexual relations with women. Peake arrived at Picasso’s villa in the South of France with a willingness to match the master in drawing animals and enough ability to keep Picasso interested in their contests and exchanges. From there, he exhibited two other qualities that were guaranteed to capture Picasso’s imagination — his horsemanship and his association with Hollywood. Picasso was not Peake’s first celebrity pal by any means. Peake/Picasso has images of Peake at Rancho Jabali with Audrey Hepburn and with Gregory Peck, who was married there. The Walt Disney Company made a short film called Cow Dog at the ranch that is included in the exhibit. His life was highly publicized, and his persona well documented even while he was still very much alive.

But Peake’s air of authority was perhaps most importantly drawn from his confidence as a traveler between these realms. One way to look at it would be to say that, for someone like Peake, making friends with Picasso was easy because he was used to being around other celebrities, but in terms of Peake’s own life and world view, this friendship clearly represented something that was on a different level. First through Diego Rivera and then Rico Lebrun, Peake strove to discover himself in relation to an acknowledged master and mentor. Particularly in the case of Lebrun, this quickly passed over into something more reciprocal and democratic, so that by the time Peake squared off with Picasso, he was ready to participate on an equal basis in the dialogue. It went beyond words.

To some extent, the culture of a given place and time blinds its participants to any peculiarities of what they consider normal and tasteful. Dressing up in Spanish costumes and dancing to mariachi music would be odd in the suburbs of Connecticut and New Jersey, but here it signifies much the same spirit as does the ubiquitous Fourth of July parades that small towns hold all over America. After seeing Peake/Picasso and wrestling with that legacy, it’s a little easier to see that Fiesta, despite everything about it that’s fake and throwaway, represents Santa Barbara’s priorities. The Hispanic metaphor is our way of saying that first and foremost, we are the descendants of a Spain of the spirit, one that manifests in life and in art, and in the most ancient equally with the most modern of things.