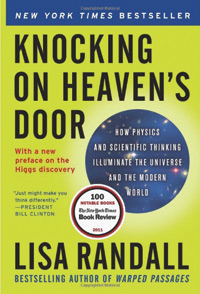

Book Review: Knocking on Heaven’s Door

Lisa Randall Writes a Book of Big, Mind-Bending Ideas

Knocking on Heaven’s Door by theoretical physicist Lisa Randall isn’t a book I would take to the beach on an August afternoon, though one might argue that this is a book that deserves to be read outdoors, in view of the sky and the horizon, an appropriate place for a book of big, mind-bending ideas about the nature of the universe.

I don’t consider myself scientifically minded. Prior to reading this book, I couldn’t explain the purpose of the Large Hadron Collider if my children’s lives depended on it. I’m the typical layperson for whom Lisa Randall wrote this book. Unlike Sheldon Cooper, the persnickety fictional scientist from the Big Bang Theory, Randall tries, admirably and ably, to open a window on the most complex and intricate scientific theories and notions currently being studied and debated by the real Sheldon Coopers of this world. This is no easy feat, and along the way Randall touches on the historically contentious relationship between science and religion – an inherently risky proposition for a mass-market book – though, as Randall writes, “Over time, as technology permits us to scale new regimes, science and religion will have more overlapping domains and potential contradictions can only increase.”

Technology has changed the way most people live today, as anyone who uses a smartphone and the Internet knows, but what is often forgotten in our rush to embrace technology is the underlying science that makes the latest gadgets and tools possible. Randall is a passionate and proud ambassador for pure scientific inquiry for its own sake and has an insatiable appetite for understanding the way the world and the universe work, whether this means peering as far as possible into the outer reaches of the cosmos or into the internal structure of matter itself.

Heavy stuff to be sure, but Randall argues that scientific inquiry and investigation frequently lead to spectacular breakthroughs that affect how we live, work, and understand our place in the larger scheme of the universe. In the course of seeking answers to fundamental questions, we discover something that turns out to have great utility. The electron, as Randall notes in her final chapter, “was discovered with no ulterior motive, yet electronics have defined our world.”

I confess that swaths of this book sailed right over my head. Despite numerous charts and illustrations, I can’t claim to understand black holes, quarks, string theory, or the Higgs boson much better than I did before, but there was plenty to wrap my head around, such as the chapter titled “Risky Business,” in which Randall contrasts the vastly different methods employed by scientists and economists to evaluate risk and probability. I’m not sure that the economists and investment bankers who precipitated the 2008 economic meltdown had enough appreciation for the difficulty of making accurate predictions about complex collateralized debt obligations and credit default swaps; more than five years later, thousands of people are still paying for that failure.

Despite her vast accomplishments and fame as a writer and scientific personality, Randall retains the humility of one acutely aware of just how much she will never know.

4•1•1

Lisa Randall comes to town as part of UCSB’s Arts & Lectures series Saturday, March 8, 3 p.m. at Campbell Hall. $20 general; $10 students. Tickets and info: 893-3535 or artsandlectures.sa.ucsb.edu.