Review: Under the Umbrella at the Santa Barbara Historical Museum

Exhibit Explores Lutah Maria Riggs’s Impact on Santa Barbara

While her mentor George Washington Smith remains the better-known figure, the career of prolific architect Lutah Maria Riggs captures a broader range of the styles that have made Santa Barbara renowned as a beacon of innovative design. While Smith set the tone for our city’s best-known public buildings, it was Riggs’s transition from Mission to Modern that laid the groundwork for such extraordinary examples of late-20th-century Santa Barbara architecture as the Crawford and Blades houses by Thom Mayne/Morphosis. In Under the Umbrella, currently on view at the Santa Barbara Historical Museum, a wide array of artifacts, many from the collection of the UCSB Art, Design & Architecture Museum, have been brought together to tell this unusual woman’s inspiring story.

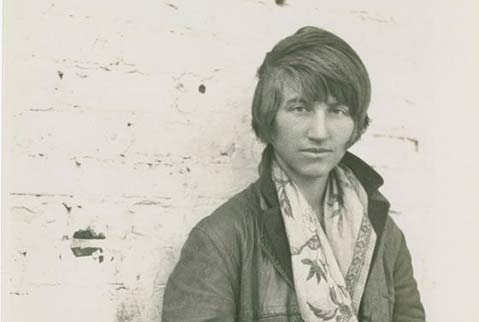

The fact that Riggs became an architect at all stems from a combination of chance and her own initiative and persistence. While still a teenager, she won a scholarship to the University of California at Berkeley through a contest based on delivering the most newspapers. As a woman entering what was at the time an exclusively male field, Riggs had to work hard to be accepted even at the most basic level of apprenticeship. She did, however, have the good luck to be in the right place — Santa Barbara — at the right time, which for her meant 1924, the year before the big earthquake. Her field trips to Europe with George Washington Smith in 1924, and again in 1928, allowed her to become familiar with the best practices of Spanish, French, Italian, English, Swiss, and German developers. When she was given the opportunity to design buildings in California, Riggs demonstrated skills in drafting and in siting projects that won her the confidence of both her fellow architects and her many clients.

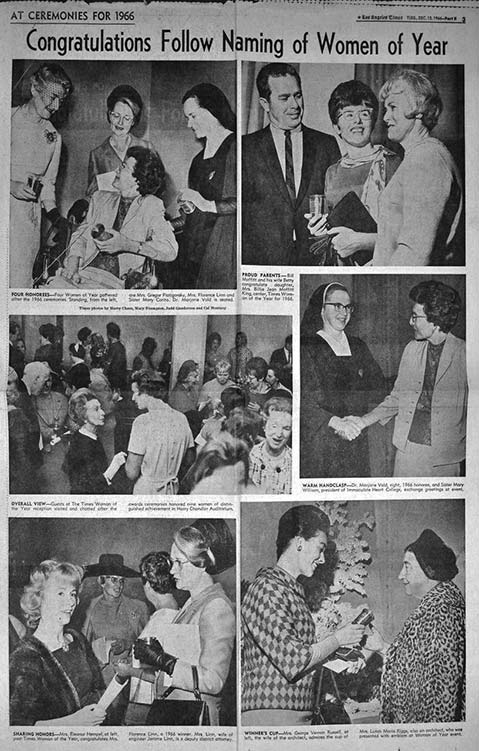

By the time World War II came along to interrupt what had been a very busy period for California architecture, Riggs had completed a number of impressive projects, including the Lobero Theatre, the Von Romberg house in Montecito, and the City of Rolling Hills, a gated community of elegant ranch houses on the Palos Verdes Peninsula. Although she managed to sneak in one more important Santa Barbara project for the Botanic Garden during the war, she spent most of it designing sets at MGM Studios in Hollywood.

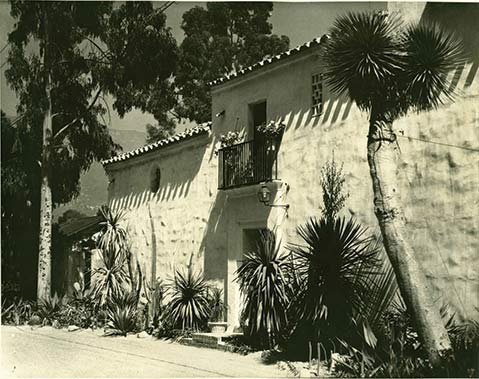

The jewels of this show include a series of beautifully rendered architectural models that begin with the Von Romberg house of 1937, an impressive Modern/Mission mash-up that combines massive external walls with intricate, serpentine interiors leading to grand salons and cozy, private bedroom suites. If only the Baron von Romberg had lived to inhabit his magnificent home for more than a few months. He died tragically in an airplane crash shortly after the house was completed.

The other models include two houses that Riggs designed for renowned art collector and philanthropist Wright Ludington. Hesperides (1957) and October Hill (1972-73) show Riggs at the height of her powers and in uncannily close harmony with the sensibility and aesthetic of her client. The “abstract traditionalism” of these unusual homes gives them a character that is distinctively Santa Barbaran, as different from the mid-century modernism of Palm Springs as the Courthouse is from San Diego’s Balboa Park. In these cases, Riggs’s talent for asking questions designed to draw out the personality of her clients through their habits and preferences, yielding unforgettable results. Along with Joseph Knowles Jr., the other architect who assisted on these extraordinary projects, Riggs and her client Ludington reached a peak of architectural innovation and refinement that has yet to be surpassed even in our understandably house-proud region.