Jazz Master Charles Lloyd

An Interview with the Music Great Charles Lloyd

Charles Lloyd plays by his own rules — whether it’s blowing on sax with bluesman Howlin’ Wolf in Memphis while in high school or attending USC in the late ’50s by day while jamming with L.A. jazz greats by night or blasting off to rock star fame in the ’60s with the likes of the Grateful Dead, Cream, and Janis Joplin.

Lloyd continued his own journey when he suddenly disappeared from the music scene in the late ’60s — at the height of his popular success — to watch hawks soar over Big Sur and to nurture his spirit. When Lloyd … slowly … emerged from Big Sur in the mid-’70s, it was to move to Santa Barbara: first by living part-time at Beach Boy Mike Love’s Montecito beach house and then moving permanently to the hills of Montecito in the ’80s.

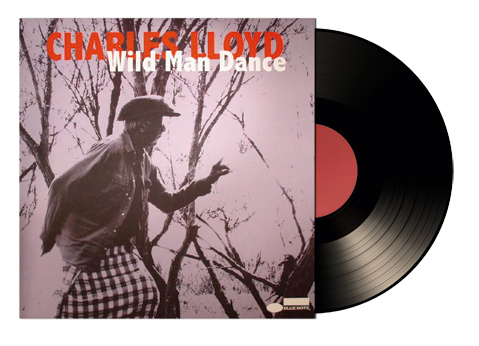

Since then, from what he describes as his “laboratory and ashram” close by the Vedanta Temple where he worships, Lloyd expanded his vision. For the last 30 years, he has performed around the world on tenor saxophone, flute, and Hungarian tárogató and made 17 records of extraordinary range, including his Wild Man Dance suite, released last week on Blue Note Records to enthusiastic international reviews. On Monday, April 20, Lloyd was inducted as a 2015 Jazz Master by the National Endowment for the Arts, the “highest honor that our nation bestows on jazz artists,” according to the NEA.

On a recent Saturday at home, just 24 hours after the New York Times had published a long, flattering profile and featured Lloyd’s work on its popular Popcast, he was days from departure for the NEA ceremony at Lincoln Center, and from his performance of the North American premiere of his “Wild Man Dance Suite” before the ancient Temple of Dendur, an Egyptian sanctuary reconstructed within New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Sitting in his kitchen, though, Lloyd was serene, not excited.

“I don’t live in excitement like that. My approach to excitement is that that stuff leads to expectations, and expectations can ruin many a great joy,” he said. “Basically what is going on with me is that I live in the now. I don’t get into future.”

This Thursday, April 23, in San Francisco, Lloyd kicks off a four-night stand with three different bands: first the “Wild Man Dance Suite” ensemble made up of American, Greek, and Hungarian musicians; second his main working New Quartet with Jason Moran (piano), Reuben Rogers (bass), and Eric Harland (drums); and third, Charles Lloyd and Friends, featuring cosmic guitarist Bill Frisell.

Lloyd then brings Charles Lloyd and Friends, including Frisell, to his annual residency at the Lobero Theatre on Tuesday, April 28. “I like playing here at home,” Lloyd said. “The people who are inviting us — they care. It’s like that.”

Lloyd has had a busy spring. In New York in March, on his 77th birthday, he rocked the Village Vanguard with the New Quartet, to more gushing ink in the New York Times. A documentary, Arrows into Infinity, released on DVD last year about Lloyd, just became available on iTunes. It’s codirected and coproduced by Jeffery Morse and, crucially, by Dorothy Darr, the painter, filmmaker, photographer, and architect who is Lloyd’s longtime partner and business manager. After the Lobero gig, Lloyd will headline festivals across the U.S. and Europe, starting with the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival on May 2.

On that recent Saturday, Lloyd had just finished off a cold smoothie and was wearing a thick jacket and a knit cap against the resulting chill when we first met. He was “looking for the right zone,” he said, which is where he wants to be whether engrossed in a solo onstage or when talking to The Santa Barbara Independent at home.

Lloyd’s home with Darr, designed by her, is amazing: Beyond the walls filled with artworks, many by Darr herself, beyond the grand piano and the resting sax, through soaring living room windows, across parched grass, lay a vertiginous view of the Santa Barbara coastline and islands.

Lloyd signaled that we should sit at the kitchen table so we could see the harbor view as we talked. Lloyd has an expressive voice, and he usually answers with an opening motif, inventive riffing, modulation to related concepts, and then, engagingly, resolution to the original question.

Drought

Like everyone, the drought is on his mind. Lloyd is a “water guy,” he said, starting with his birth in Memphis during a flood. Arrows into Infinity features long cuts of ocean waves, rivulets across pavement, and bright orange fish swimming.

“It hurts,” he said of the drought, which is particularly bad in the aquifers underlying Montecito. “When we moved up here, there was a creek that ran year-round. Things like that are big concerns for me — our environment.”

“I’m not going to solve this,” he continued, “but I want to make a sound universe that can transform things. That’s what I’m working on. I would be a hypocrite if I just told you that we have to make a plan, because I’m getting ready to go out there and get on a whole bunch of fossil-fuel airplanes.”

NEA Jazz Master

The 2015 NEA Jazz Master Award likewise contains crosscurrents. Given Lloyd’s intense, international composing, performing, and recording, he’s not contemplating victory laps on the lifetime achievement circuit. His universalistic music transcends “Jazz” in the popular sense. The NEA is government, which Lloyd bypassed during the Cold War to perform in the USSR at the invitation of Soviet artists. Lloyd, however, appreciates validation, and he’s sensitive to having been overlooked.

“I learned a long time ago that I would have to be able to endow my own creativity,” he said with a catch, quietly looking at the harbor, “and, in so knowing, and in so doing, I never held my breath for the gold-plated watch because I didn’t expect it; but when it does come like this thing [the NEA award], it’s an honor because of the company that I keep, like Miles, Ornette, Sonny Rollins, Wayne.”

Lloyd pondered ageism in institutional arts since Moran, 40, his principal working pianist, received about $500,000 from a MacArthur Foundation “genius grant” in 2010 “to do what you want,” while the NEA Fellowship is much less and is awarded to older musicians. This year, the musicians inducted with Lloyd are jazz composer, pianist, and leader Carla Bley, 78, and composer, hard bop saxophonist, and leader George Coleman, 80.

“To at least be considered in your lifetime, in a culture that hasn’t been very kind to its artists because of the setup of the world, it’s a great honor,” Lloyd said, slowly. “My spiritual practice is about nonattachment and to beware of cravings. I learned to sublimate that stuff and not be chasing that thing. So, of course, it’s great.”

Race at USC

Lloyd’s performance at the seminal 1966 Monterey Jazz Festival was released as Forest Flower, with Lloyd in full cry on his tenor on the bright-yellow album cover. Backed by some of the best jazz musicians ever (Keith Jarrett, piano; Cecil McBee, bass; and Jack DeJohnette, drums), the record caught the business comet, sold more than a million copies, and created a ’60s cultural “moment” for boomers before the decade turned dark.

Lloyd and his band were virtuosos, and their cross-rhythms, complex progressions, and deep experimentation blew away those of psychedelic rockers. Lloyd’s image was broadly inclusive, intelligent, and post-racial.

What was it like, though, for Lloyd before he became a totem of the Woodstock nation, when, as a teen, with a “gendarme” on his tail, he left segregated Memphis to attend the crew-cut University of Southern California in the late 1950s?

“The life on campus was all white and very strange; I was the invisible man,” remembered Lloyd, in a nod to Ralph Ellison, “but I was a philosopher, so I could see quickly what was going on.” When he was leaving Memphis, he received offers from USC fraternities to rent rooms in their houses during the summer before he began his freshman year. Solicited, that is, until he showed up.

Within USC’s School of Music, he faced resistance. “I had this big fantasy dream; I wanted to integrate Bartók with Duke Ellington and all kinds of Charlie Parker stuff, and I had to make these correlations between J.S. Bach and Charlie Parker. No one really had any interest in any of that, so I realized that I was in the wrong place, but for my parents, I stayed.”

“Education was the ticket” that Lloyd’s “black middle-class family” emphasized, where you had to graduate from college, which he did in 1960. “But I was bit by the cobra, so it was too late for me to not play music,” he said.

Lloyd escaped into the jam sessions of L.A. during a historically fertile period. “There was great music everywhere, so I played all the time. I did a duality thing [with campus life],” he said. “I hung out with Ornette, Billy Higgins, and Scott LaFaro, a close friend; Gerald Wilson had a big band, and so we all played in that, too. There were a lot of sessions, a lot of places to go. We had a beautiful community.”

A coda is that about 10 years ago, USC called on Lloyd in Santa Barbara to solicit a life estate contribution of his compound to a USC endowment. “Then upon my ascension, they could make it a think tank,” Lloyd recounted. “USC got excited, and the Dean of the School of Music wanted to meet me. It was a change over from when I was there.”

But it didn’t work out. “We just had to agree to disagree,” Lloyd said a bit fiercely. “USC said they would have a building in my name. I don’t need a building in my name. That’s not what I need. I need to play this music, and I need to touch people’s hearts and spirits.”

The New Record

His new record, Wild Man Dance, came about after Lloyd played the Jazztopad Festival in Wroclaw, in western Poland, in 2011. “They said that it was the best concert they ever had, and they commissioned me to write an orchestral-length work,” he said.

“Wild Man Dance Suite” was composed by Lloyd during hikes and swims and “percolating” in Santa Barbara before he returned to Wroclaw to perform its world premiere in late 2013. In addition to the American jazz musicians — Gerald Clayton, pianist; Joe Sanders, bassist; and Gerald Cleaver, drummer — Lloyd’s backing group included Sokratis Sinopoulos, of Greece, playing the bowed lyra, and Miklós Lukács, of Hungary, on cimbalom, a large frame hammered dulcimer.

“I wrote this music, and I heard it at home, and I played it for Dorothy, and the musicians heard it, and we went on the journey,” he said, “so we got blessed, you know — that is what that was. The audience was ready to receive it.”

In “Flying over the Odra Valley,” the first of Wild Man Dance’s six movements, Sinopoulos on lyra bows an ancient folk melody high over the abstract intervals of Lukács’s cimbalom. Lloyd waits … and then joins after three minutes with a tender melody that he develops around a modal core over unsettling piano chords, bass, and drumming. Sanders’s bass follows with an earthy solo, and Clayton then solos with dissonant chords. A rhythmic storm builds. Lloyd returns, flying above the tumult.

The suite flows to “Gardner” with beautiful melodies from the lyra supported by piano and bass. Lloyd blows long meditative lines, adding energy and space, moving forward in ever-more-emotive phrases, soft, uplifting, climbing higher.

In “Lark,” Clayton’s piano sets the scene with block chords. The lyra’s plaintive melody is harmonized by bowed bass and supported by cimbalom arpeggios and the drums lightly tapping. Lloyd waits again as dissonance builds, this time for six minutes, and then piles on, pulling and pushing. A dramatic piano solo transitions to swinging 4/4 time, complete with walking bass and Clayton channeling McCoy Tyner to Lloyd’s Coltrane.

“River” is the most accessible movement in this era of download and subscription. Clayton’s transition previews the chart, and Lloyd opens with a riff as memorable as any in music recently. After solid complementary B and C sections, Lloyd steps out with a tight swinging solo that’s straight from Memphis. Clayton’s piano, Sanders’s bass, and Cleaver’s drums follow with inventive solos. The rhythm then moves essentially to a four-beat rock groove. Lukács, in a highlight of the entire work, elevates over the three-chord vamp with an extraordinary cimbalom solo. Lloyd returns, tosses the opening melody around with Clayton, and ends the movement triumphantly.

“Invitation” returns the beautiful bowed lyra over harmonized bowed bass, with the piano joining for a trio and the percussion making it a quartet. Lloyd again is patient and lets his musicians jam, coming in finally with long pastoral lines against unresolved chords that gradually increase in intensity before he plays a sensitive outro.

In the final movement, the namesake for Wild Man Dance, Lloyd comes in with a whisper, evoking earlier melodies, before playing the theme in a soft Lester Young tone. The rhythm section responds with broad support. Lukács hammers broad angles on the cimbalom, interlocked wonderfully with Cleaver’s drums. Lloyd restates briefly. Sinopoulos’s lyra — propelled by a driving bass line and locked drums — soars on an extended improvisation: Jimi Hendrix and Stéphane Grappelli and Vassar Clements. Lloyd retakes control initially with a Middle Eastern vibe leading to free association among musicians, and then Lloyd brings the entire 74-minute work to a gentle close, to festival applause.

Lloyd is in superb form, and the band sounds great. The cimbalom and the lyra provide vital colors. The recording quality is excellent.

This sounds weird, but, when first listening to Lloyd’s first solo on Wild Man Dance, I felt Santa Barbara Pride similar to watching local Katy Perry nail February’s Super Bowl halftime performance.

Next?

Lloyd said “he’s not good enough to quit yet.” So, what’s next? “I have lots of stuff going on, but nothing I can report to you,” he said officially. “What I’m working on, these sounds and these tones that are coming to me, I don’t have words … I can play it.”

Lloyd took me up some stairs to his rooftop and into a beautiful workspace with sweeping views of the channel. “I want you to hear something,” and he fiddled with tiny track lists on a laptop hooked to killer speakers.

Click: An opera swelled through the room. Whoops. He clicked it off. “I’m an opera guy,” he said. “I listen to the Met on Saturdays.” Click: an old blues snippet. (“Oh, why my baby, why? Ooohhh…”). He clicked the laptop again. Out of the speakers came Jason Moran, speaking from the stage of the Village Vanguard performance in March, introducing Lloyd’s band: “Sometimes you do things to realize your dreams,” Moran says, “and this is realizing a dream tonight to play on a stage with Charles Lloyd, Eric Harland, and Ruben Rogers.”

Lloyd’s New Quartet launches immediately into descending lines, following Lloyd on sax. Moran takes a solo on piano with cascading chords, the bass and drums instantly responding.

I glanced over, and Lloyd had a gigantic smile.

He raised his voice above the speakers to say that he went to Poland with six movements of the “Wild Man Dance Suite,” but this is a seventh movement, not recorded in Wroclaw. “I didn’t take it because I didn’t think it was completed,” he said. “When I got back from touring and recording over there, and I played it to myself, it was pristine. During the time I was gone, it became complete. So what you are looking for is looking for you.”

Lloyd’s sax returns after Moran’s solo, like an animal gliding out of the trees in a European forest. It picks up pace, and a secondary theme emerges. The rest of his quartet is instantly there.

Lloyd is leading some of the finest musicians in the world into new territories, with no concessions to being an elder statesman, with no boundaries, with no rules but his own.