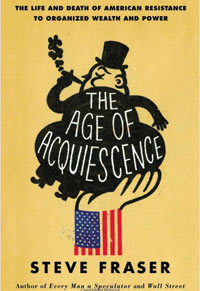

Books: The Age of Acquiescence

Steve Fraser’s New Book Shines a Light on the Second Gilded Age

Why didn’t the Occupy Wall Street movement happen sooner? And why is the only real political resistance in contemporary American politics coming from the right, in the form of the Tea Party, rather than from the left? These are the central questions animating Steve Fraser’s exquisite new book, The Age of Acquiescence: The Life and Death of American Resistance to Organized Wealth & Power. In order to answer them, Fraser leads the reader on a fascinating and relevant journey back to what he calls “the long 19th century,” when the infrastructure of the American economy was being created.

Fraser is adept at identifying the threads that tie the present to the past, and this is useful because Americans are not known for their historical memory: our collective attention is relentlessly focused on the present, on the 24-hour news cycle and the fleeting issue of the moment. Fraser reminds us that popular resistance is part of the American DNA, dating to the fierce intellectual arguments between Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton over the appropriate role of the federal government. As the United States developed and expanded, as canals were dug and railroad routes laid, artisans and craftsmen resisted organized capital, abolitionists resisted slaveholders, and those who valued equality resisted those who prized individualism.

Social tensions ran high and hot during the first Gilded Age, and between 1886 and 1893, state governors called upon the National Guard more than 100 times to quell labor unrest and protect private property. New York bankers and Wall Street speculators were targets of vitriol, hatred and, very often, violence. Convinced that too much money and influence accumulating in too few hands was dangerous, citizens argued, debated, marched, and fought in the streets. Capitalism was not the foregone conclusion that it is today. Who controlled the means of production meant a great deal to the proletariat of the first Gilded Age.

So what happened to the American spirit of resistance? Fraser points to two major events. First, there was mass consumption driven by advertising that focused on self-realization and self-identity through products and brands. Second, there was the financialization of the American economy. The ground shifted beneath the feet of working people when the U.S. abandoned manufacturing for finance; capital became more fluid and less tethered to locales like Youngstown, Ohio; Detroit, Michigan; and Gary, Indiana. Union membership and influence waned, as did working-class identity and solidarity. By the late 20th century, manufacturing jobs had been exported abroad while work in the U.S. became more contingent, uncertain, and precarious.

The financialization of the economy, coupled with weakened fealty to the ideology of the New Deal, has produced a second Gilded Age where the chasm between the wealthy and everyone else is wider than ever. A real threat now is that the remorseless logic of the free market will destroy the free market and, quite possibly, the planet. With scholarly skill and a common touch Fraser illustrates an inescapable irony: In creating our second Gilded Age, the wizards of American finance have liquidated the assets that built the first Gilded Age.

You might say that when it comes to American-style capitalism, some things never change.