Das Williams Pushes for I.V. Governance

Can Das Williams’s AB 3 Bring a Voice to Isla Vista?

In the summer, Isla Vista is perfect. The cool coastal breeze softens the heat rays bouncing off the asphalt, and the feeling of camaraderie among the college students who stayed in town for the three warm months is great. An un-crowded beach town during the summer — who would want to be any place else?

We all know I.V. is the opposite of light during the remaining nine months of the year. To call Isla Vista a densely populated unincorporated area is a bureaucratic buzz phrase that dulls the image of thousands of students packed into shabby apartments.

We all know about the house music that blasts from open-door parties on Del Playa where keg stands and Gaucho Ball last until the beer — or “plastic handle” vodka — runs out. We all know about the skinny-dipping, the shopping-cart racing, and the rooftop dancing. We all also know about the violent elements — the rapes, drug deals gone bad, and the tragic falls from the bluffs.

But most of us would like to pretend the chaos does not exist. At least not to the degree we can do anything about it. But Elliot Rodger changed that, at least for a while. When Rodger’s brutal rampage took the lives of six young college students, the collective consciousness determined it was time to wake up — as it did 14 years ago after David Attias struck and killed four students one horrific night.

Last summer, the UCSB Board of Trustees — operating independently from university administrators — funded an extensive study on how to fix I.V. It produced a laundry list that included UC buying student housing and other solutions addressing the overcrowded conditions. But at the top of the list was the establishment of a local governing structure.

That might seem like a no-brainer, but for the last 40 years, as the UCSB student body grew and grew, no one was really running the show — not the university, which has no legal responsibility over the Isla Vista area, nor the County of Santa Barbara, which is technically in charge but financially stressed. The only elected authority is the I.V. Recreation & Park District, which was formed in 1972 but only after a bitter battle pitting outraged students against just about everyone with authority. Even its next-door neighbor, Goleta, which had also long been an unincorporated area of tens of thousands, would repeatedly refuse to accept cityhood if I.V. was to be part of the plan.

When Goleta did incorporate in 2002, it did so without bringing along 15,000 college kids and their bicycles. Isla Vista and truly became an orphan left out in the cold. Enter State Assemblymember Das Williams. A son of Isla Vista and an unorthodox, ambitious politician, he launched an ass-backward approach to the problem. The great part about ass-backward approaches is that they sometimes work.

Politically Risky?

Das Williams sponsored a bill, AB 3, which offers a form of self-governance for Isla Vista. His ass-backward approach is that he completely skipped the usual method of creating a voice for the politically disenfranchised. He bypassed working with LAFCO (Local Agency Formation Commission), a group made up of regionally elected officials who have repeatedly refused to grant separate status to I.V. Cityhood attempts failed in the 1970s and 1980s because it determined the area lacked the tax revenues to support the amenities included in a city. Also, property owners lobbied against it with a vengeance, fearing a city could implement rent control. Others worried parking control would obstruct beach access.

To take this unorthodox path, Williams risked political capital. And a lot of people asked why. Why would a politician well known for his ambition take on a project that does not appear to aid his immediate political goal? Williams has announced that he will be running in 2016 to represent the county’s 1st District, which encompasses Carpinteria, Montecito, and much of the City of Santa Barbara — decidedly not Isla Vista.

When Governor Jerry Brown, looking to fund education, abolished the state’s redevelopment agencies in 2012, Isla Vista took a $6 million annual hit — money that had been intended for sidewalks, landscape, and new housing. Williams had been a strong advocate for their dissolution. He said at the time, “… if I have a choice between schools and redevelopment agencies, I’m taking schools.” Perhaps this stance, in part, explains why he has gone out on a limb for Isla Vista.

Or one can argue Williams’s Isla Vista activism is in his blood. Certainly that is the position of his father, Malcolm Gault-Williams, who was part of the last failed attempt to establish cityhood, led by the longtime activist Carmen Lodise. Gault-Williams recently said that though he might still hope for an eventual I.V. cityhood, it is obvious something must be done now, and this is Isla Vista’s best shot: “… [the bill] is being spearheaded by a man who grew up in Isla Vista, who knows its complexities and understands its problems, personally.”

What Is AB 3?

In recent years, students had seriously studied the possibility of creating a community services district, a practical model for Isla Vista residents to speak to the county and UCSB. The notion is to create a nucleus for the crammed, jammed, and lawless place that is boxed in by the Pacific Ocean, Devereux Slough, the UCSB main campus, and the city of Goleta.

Boiled down, AB 3, if signed by the governor, would place an initiative on the 2016 ballot allowing Isla Vista residents to vote on establishing a community services district, a quasi-city with an elected board of five members, and two appointed seats, one by county supervisors and one by the UCSB chancellor. The district would be funded by taxes from utilities, allowing for a planning commission, tenant-landlord mediation, augmented police officers, a parking district, and other services.

When the bill was first introduced, Williams stressed the process was just the beginning and its language would be drafted based on the community’s needs. Since January, a group of students and homeowners have met more than 50 times to go over particulars so many times it left observers dizzy.

Radioactive

In 1971, 18-year-olds received the right to vote, and everything changed. Already a political hotbed of student activism against the Vietnam War, Isla Vista became radioactive, eventually turning the county’s 3rd District, which included I.V., into the swing district. The Democratic machine set up shop in the college town and, for the most part, was able to register enough campus voters to determine the balance of power at the Board of Supervisors.

The rub has always been that the thousands of Isla Vista voters could not exert any real local political will of their own. There is simply no vehicle for it. “I’ve always held that it’s only when residents have responsibility that they will pay attention to the rules,” Lodise said last fall.

The establishment of a community services district, champions argue, could eventually strengthen enforcement of overcrowded apartment complexes. Four beds in a garage are not uncommon. But this raises an uncomfortable question: Where would forced-out tenants even go?

Nevertheless, the special district, ultimately, could begin to change the sense of anarchy that makes I.V. wild and free, and dangerous.

Ass-Backward

That said, there are a host of issues opponents raise. For starters, the process of setting up a district usually requires petitioners to complete a fiscal study. Williams decided that was initially unnecessary and charged forward. Since then, various groups have chipped in the funds for a study to determine which services a newly formed district would even be able to realistically support.

Others wondered why Williams did not push forward a bill that’s been lingering in the halls of Sacramento, authored by former state senator Robert Lagomarsino in 1972 and signed by governor Ronald Reagan, that would create an I.V. community services district. But when the bill passed, community activists were so gung-ho about cityhood the initiative never got enough signatures to qualify for the ballot.

Williams did not revive that bill, he said, because it would have required the approval of LAFCO, that intergovernmental agency he has long distrusted, blaming the 45 years of I.V.’s lack of self-governance solely on LAFCO boards. Critics who charge his bill takes the matter outside of local control — and to Sacramento — fail to see that it was those authorities who have denied Isla Vista residents the ability to create their own destiny, Williams said: “That seems not to be what local control is about.”

Nothing Funny About LAFCO

If you have never heard of the acronym LAFCO (pronounced laugh-co), consider yourself lucky. Williams’s public frustration toward the agency intensified in the last year, calling the situation in Isla Vista an “emergency.” He seemed to take personally what he saw as the commission’s long-term negligence. “People are being hurt by the fact that Isla Vista does not have adequate local services. There is something that can be done about it,” Williams said in April. “I think that frankly outweighs LAFCO’s opposition.”

LAFCO commissioners have insisted that it is not a proactive agency; it can only respond to received applications. AB 3, a bill they discussed ad nauseam at their monthly meetings, is, according to most of them, essentially an undemocratic, blank-check, bypassing process.

As the bill is written today, LAFCO would be allowed limited input — it could review the proposed district and could recommend whether or not it thought the district should go to a vote of the people. It would not, however, be able to prevent the vote outright.

Third District Supervisor Doreen Farr, who chairs the LAFCO board, has deviated from her fellow commissioners, calling the bill the “best chance” for the community, noting that if a district proposal went through LAFCO, only property taxes could be collected, but AB 3’s utility tax would be paid by all residents. Also, she admitted that the county is strapped for funds, so even though this year the supervisors were able to allocate more than a half-million dollars to improving Isla Vista, it is not part of a guaranteed annual budget.

Aside from LAFCO, Williams and his district director, Darcel Elliott, have relentlessly lobbied every elected official in the region for support. And the efforts are working.

Hertzberg Comes to Town

State Senator Hannah-Beth Jackson, despite being a longtime political and personal comrade to Williams, has shied away from taking a position on the bill before it gets to the senate for a vote. When asked, she said she is “anxious to see how the feasibility study comes out.”

Even more surprising was the support given the bill by political heavyweight State Senator Bob Hertzberg, who chairs the senate local governance committee. In the past, he has worked to strengthen LAFCO’S powers yet appears to be shepherding the bill through the Senate. It has already zipped through his committee. Three weeks ago, Hertzberg made a trip up to Isla Vista “to understand” the community. For the most part, it looked like a love fest, but when he asked I.V. Rec & Park staff, which maintains 25 parks throughout the area, why the park district was not consolidated into AB 3’s community services district, he was told it was because Rec & Park had existed for decades. That did not sit well with Hertzberg, who noted that the governor does not want to establish new districts that would clutter government.

Since then, concern has grown about the fate of the park district, an agency receiving $1.4 million from I.V. bed and property taxes. The crux of the matter may be that the park district’s nine full-time employees are members of SEIU (Service Employees International Union) Local 620, the local chapter of a public employee union. Williams, who has had long, close ties with the union, assured an SEIU rep earlier this year that AB 3 would not undermine union contracts. If passed as presently written, that might be true. The bill specifies that the special district would not provide the same services currently offered through the park district. But if Hertzberg is correct, and the governor would veto a bill that creates another entity to a relatively small population, Williams would have a tough decision to make. “Which direction he would go is anyone’s thought,” Rodney Gould, general manager of the park district, said.

Williams does not see it as either-or: dissolving the park district and angering his union allies or risking a veto. “There may be other options to satisfy the governor’s opinion to simplify government,” he said. “The only reason this has become an issue is because Hertzberg was asking good questions,” Williams told me. “And we want to be able to answer … any questions that the governor will pose to us.” The bill is expected to be on Brown’s desk later this summer, as it looks like it will pass off of the Senate floor by September 11. Williams, in an act of faith, noted that of his 40 bills that have reached the governor’s desk, Brown has only vetoed one.

Baby Das

Faith plays a part in William’s life, past and present. As a kid, Williams said he was a skeptic. He would spar with his grandfather, an Indonesian member of the Dutch Royal Navy during World War II, who had developed a deep belief in God witnessing the horrors of Japanese prison camps. Young Williams would pick apart every line in the Bible, just to annoy him, saying science was his only religion. But by the time he was 17 and “had lived more of life,” he began to embrace Christian teachings.

As a teenager, his upbringing was far from stable, moving between his evangelical mother’s house in Ventura and his Maoist father’s in Isla Vista. “I wasn’t one of those kids who thought, ‘I don’t understand why my parents aren’t together anymore,’” he said.

In 4th grade, Williams moved in with his father on the 6600 block of Del Playa Drive, or the “war zone” as he called it, referring to the street’s infamous party culture. The young Williams would stand outside of the Isla Vista Food Co-op, selling newspaper articles his dad had published in the Guardian. He walked everywhere, always had a job, and would methodically deposit his earnings into the credit union.

At the time, there was hostility between the counterculture kids and the families who attended St. Athanasius Church, once located at the top of the Embarcadero loop. Williams tried to straddle both worlds. “It was an early lesson in politics,” he said. For a year in high school, he lived with his best friend’s parents, who were churchgoers. The next year he was sent to his mom, who had moved to Paso Robles. There he quickly learned to hate suburbia and to realize that most poor kids do not get to grow up at the beach. He started fights with bullies and “had no tolerance for injustice.” He dropped out of high school at age 16.

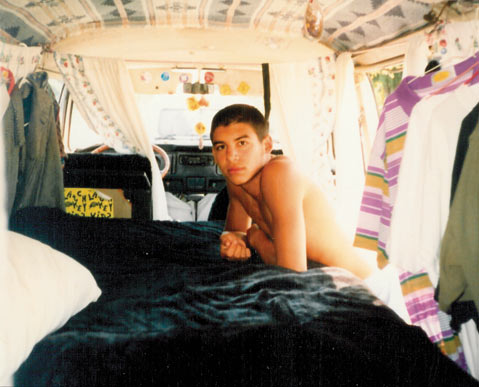

He returned to Isla Vista to live — during the warm months — in a Volkswagen bus he parked at Leadbetter Beach while attending Santa Barbara City College. Hand painted across the side of the bus was the phrase “Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité,” and what he described as “obnoxious anti-cop” bumper stickers were stuck to the back.

In 1992, Williams got his start in politics by working on supervisor Bill Wallace’s campaign for the 3rd district. Wallace — a veterinarian by trade and the champion of slow-growth politics — spearheaded aggressive door-to-door, get-out-the-vote efforts in Isla Vista.

Later Williams transferred from SBCC to UC Berkeley, taking a short detour to South Africa when he learned that Chris Hani, the communist, anti-apartheid activist, had been killed. He worked on Nelson Mandela’s ANC campaign in 1994. Williams returned energized, deciding American politics were not as “icky” as he once thought because you don’t have “to be tortured or kill people to create change.”

Four years later, Williams joined Hannah-Beth Jackson’s campaign for the Assembly, and their relationship grew from mentor-mentee to familial. It was from her he learned to “rage against the machine.” “If you ever hear one of her speeches,” he said, “you are ready to go to the barricades.” Williams was “sort of like a puppy with lots of enthusiasm” who needed to focus his energy, Jackson recalled. “I think he’s done that.” Their positions on matters are often — but not always — aligned.

Williams’s own political career started around the time he became active in PUEBLO, the community organization that received its first grant and office space from the SEIU. Over the course of his political career, the national union would be one of his top contributors, chipping in more than $57,000 to his Assembly campaign coffers. Williams champions, along with SEIU, the living-wage campaign, an effort to deter governments from contracting out public jobs. In 2003, at 29, he was elected to the Santa Barbara City Council. In 2010, he was elected to the Assembly, and he hired his 1st District director Jeannette Sanchez from the SEIU management staff.

For his part, Williams has no qualms about his close ties with the union. “Some people adjust their values based on who gives the money,” he said. Williams contended he does not. “I think everyone knows I support working people.”

People have long dubbed Williams a “young man in a hurry.” He ran for 2nd District county supervisor in 2006 before he had even completed a full term on the City Council, and no one thinks his run for 1st District supervisor will be the last seat he seeks. He continues to boast a brass, grassroots identity, and supporters laud him for being a leader who is willing to stick his neck out unlike toe-the-line Democrats who wait to see which way the wind blows. Opponents find his rhetoric calculating, his ambition opportunistic, and his personality annoying. But no one can say he is lazy.

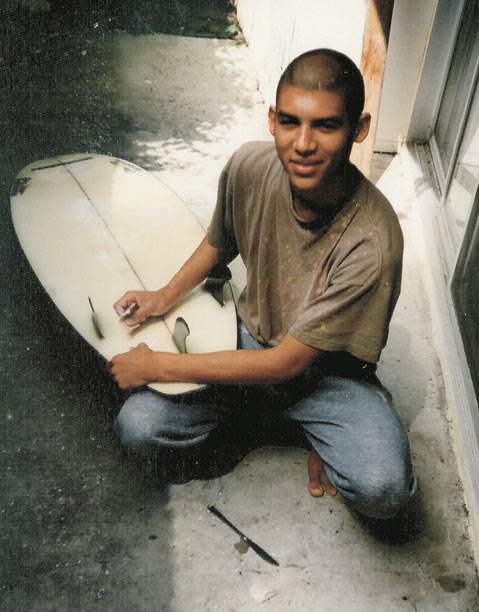

Anyone who has spent more than two minutes with the assemblymember knows he comes across well mannered and quite formal. Often dressed in suit and tie, he speaks carefully, is almost always well informed about the subject at hand, and is knowledgeable about a wide range of topics. During our many conversations, he rarely — if ever — became flustered. There is, however, an intensity about him that is difficult to describe. He is a surfer, but he is in no way laid-back.

Community Input

In the past half-year, a series of exhaustive meetings led by Darcel Elliott — Williams rarely attended — has taken place in the Isla Vista clinic building on Tuesday nights. A group of 20 or so students and homeowners have wrangled with obscurities of governance. One evening earlier this summer, I stopped by to hear the thrilling topic of “latent powers” wrestled around for more than an hour. Translated, “latent powers” means the would-be community services district could grow bigger if approved by LAFCO.

Many homeowners have long feared transient youth voting for higher taxes and leaving them with the long-term bill. Landlords have similar concerns. Chuck Eckert, chair of the property owners association, called the bill a “huge disappointment.” But, at a recent meeting, the association failed to take a formal position on the bill.

Historically, the university snubbed the unruly town, acting as if its jurisdiction ends where the campus hits the pavement. George Thurlow, UCSB’s alumni association’s executive director, has attended the meetings regularly as Chancellor Henry Yang’s appointed Isla Vista czar. Though Williams cut the UCSB campus out of the district’s boundaries, the chancellor would be able to appoint someone to sit the board. That fact caused some community members to object. “No representation without taxation,” they argued. After meetings with university administrators, Williams believes the school will likely contribute some amount of money.

While some have suggested the university’s recent presence is merely lip service, its record-breaking purchase of the three Tropicana housing properties for $156 million suggests otherwise.

Impacting I.V.’s over-crowdedness is the estimated 3,500 Santa Barbara City College students who reside there, about 11 miles away from their school on Santa Barbara’s Westside. “I was part of that horrible trend of city college kids going to I.V. that I am now working against,” Williams said. “Part of our strategy is not just AB 3 but to really help and to demand that SBCC build housing for their students outside of Isla Vista.”

The truth is a community services district, if successful, would likely help Isla Vista in a way that is difficult to quantify. A preliminary estimate found that a 6 percent utility users tax would generate about $450,000. That may not seem like a lot, supporters admit, but it could be enough for a general manager, administrative assistant, and office expenses with some change left over for programs.

Williams acknowledged the limits to his proposal. Local governance would not have stopped Rodger from killing six people, he said, but Rodger’s lengthy deranged manifesto indicated I.V.’s sense of lawlessness attracted him. Perhaps self-control would reduce the amount of that chaos.

Whether or not Williams’s gamble to gain a modicum of representation for Isla Vista succeeds or not, it will be a momentous time for Williams. In late summer, his wife, Jonnie Erika Williams, is expecting their first child, a girl, and he remains determined to keep things in perspective. His right forearm bears a tattoo of half a winged heart. His wife has the matching half on her left arm. “When we hold hands or pray,” he said, “the heart is complete.”

However when the bill does land on the governor’s desk, Williams plans to be ready to answer whatever questions Brown might raise. “I just like to be prepared,” he said.