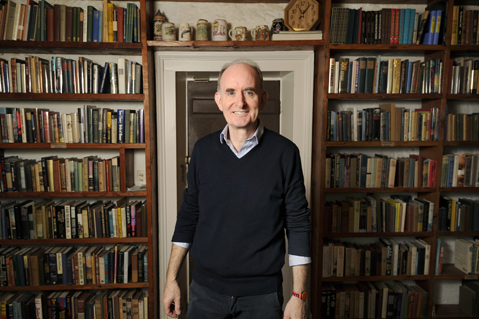

Enda Duffy and the New Irish Renaissance

UCSB Professor Duffy Brings Irish Literature to a New Generation of Students

Why is this St. Patrick’s Day different from any other St. Patrick’s Day? Because it’s St. Patrick’s Day 2016, and in less than two weeks, Ireland will mark the centenary of the 1916 Easter Rising with a series of public ceremonies. Beginning now and extending through the next six years, the Republic of Ireland will hold hundreds of memorial services, parades, concerts, lectures, exhibitions, and programs to remember the tumultuous years from the Easter Rising in 1916 through the Irish War of Independence of 1919-1921, and on to the establishment of the Irish Republic in 1922. With the extraordinary national effort that’s going into this extended celebration, it’s certain that more people than ever before will be led to actively acknowledge the history behind Irish independence. Ireland’s national television network (RTÉ) has even produced a miniseries called Rebellion that’s set to premiere in this country on the Sundance channel in April.

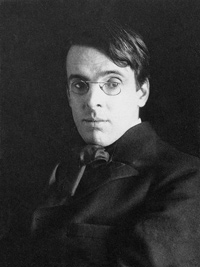

Following decades of controversy in which varying, sometimes violent opinions were routinely expressed about the propriety of celebrating what the poet W.B. Yeats termed the “terrible beauty” of the Easter Rising and its bloody aftermath, Ireland is now poised for an unprecedented effort to unite behind the notion that the history of this revolutionary episode belongs to everyone. And though the official state events that begin in Dublin next week are a long way from the whimsical version of Irish identity typically celebrated in America on St. Patrick’s Day, the 2016 date alone signifies that there’s another, bigger story shadowing the ephemeral emerald symbolism of our ersatz alco-holiday.

In 2016, what’s interesting about Ireland is not limited to its history. For example, the distinctive Irish genius for merging high and low culture into popular entertainment was amply evident in two brilliant Irish films, Brooklyn and Room, which were both nominated for Best Picture at this year’s Academy Awards. Here in Santa Barbara, we have our own genius of Irish culture in UCSB English professor Enda Duffy.

An Irish Voice in an English Department

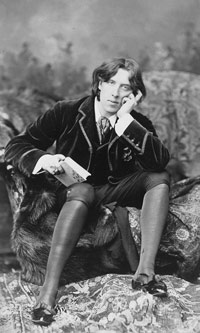

Although it may appear that the idea of Irishness held by the young revelers in green clothes who celebrate St. Paddy’s on State Street is limited to Guinness and Jameson, shamrocks and leprechauns, if you ask around early enough in the evening, it’s likely you will find several UCSB students with substantial knowledge of Irish history and especially of Anglo-Irish literature. This happy state of affairs obtains thanks in large part to Duffy, the professor who teaches Anglo-Irish Literature, one of UCSB’s most popular undergraduate courses. Year in and year out, hundreds of students flock to Girvetz Hall to hear Duffy read aloud and discourse on Oscar Wilde, Yeats, and, of course, James Joyce. Duffy, who earned his PhD at Harvard and has written two successful books, can sling academic jargon with the best of them, but his undergraduate students praise his courses for qualities like relevance and passion.

In seeking former students of Duffy’s who were willing to testify to his effectiveness, I didn’t have to look far — the office of The Santa Barbara Independent is full of them. Copy editor Amy Smith, who took Duffy’s Anglo-Irish Literature course, offers this recollection: “[Duffy was] definitely one of the most memorable professors I had as an English major. Without being overly emphatic or spelling things out for us, he seemed to find a way to remind us that the literature we were reading was by and about real people with real lives and real stories we could identify with. I think most of us can still recite at least some lines of the poems we were required to deliver to the whole class, too.”

It was this ability to connect great literature to the lives of the people who made it that brought Duffy to the attention of Frank McGinity, a longtime citizen of Santa Barbara and the indefatigable director of the California Branch of the American Irish Historical Society. In partnership with filmmakers Michael and Tina Love, McGinity has produced two films in two years, one about Don Nicholas Den, the Irishman who, among other things, saved the Santa Barbara Mission (for a thorough and laudatory account of Den’s days here, see Nick Welsh’s 2015 article at independent.com/denbrothers), and the other an educational short derived from a lecture delivered by Duffy last June to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the birth of Yeats. Thanks to the hard work and imaginative filmmaking of the Loves, the resulting DVD deftly weaves together Duffy’s analysis with beautiful footage of County Sligo and other Yeats-related sites in Ireland and includes readings of Yeats poems and commentary on the poet by none other than T.C. Boyle. The 32-minute video, which is called The Passion of Yeats, can be purchased at Chaucer’s Books.

Due to his close association with the struggle for independence, Yeats occupies a special place in the canon of great Irish writers. As he himself acknowledged upon receiving the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1923, just one year after the founding of the Irish republic, “this honour has come to me less as an individual than as a representative of Irish literature,” adding that “it is part of Europe’s welcome to the Free State” of Ireland. Despite his heartfelt commitment to the nationalist cause, Yeats took a cautious approach to such revolutionary actions as the Easter Rising, even going so far as to withhold his poetic response to the events from publication until 1920. In fact, at the height of the fighting in 1920, Yeats was far away from Dublin on a lecture tour of the United States with his young bride, Georgie Hyde-Lees.

The poet expressed particular delight in the landscape of coastal Southern California, and the mystically inclined couple surely got a kick out of passing through Summerland on the train, as its name is derived from a theosophical term for the afterlife. It was in that year that Yeats published his most influential work, “The Second Coming,” a poem which has fascinated readers the world over ever since, and that is responsible for the titles of two other major works of literature — Things Fall Apart, Chinua Achebe’s classic 1958 novel of post-colonial Africa, and Slouching Towards Bethlehem, the 1968 collection of literary nonfiction that established Joan Didion as the preeminent chronicler of California’s role in the culture of the 1960s.

For Duffy, the journey that led him from a small town in the west of Ireland to a professorship at UCSB began in Northern California, at the California State University campus in Chico, where he came on a traveling fellowship in 1982. “I was meant to return to Ireland with a degree in education, which I did, and to become a teacher there, which I did not. Some of the professors I met in the English department at Chico informed me that it was possible to be paid for attending graduate school in the United States.” Duffy was then admitted to the PhD program at Rutgers, and he spent a year there before transferring to Harvard, where he finished his degree. His adviser at Harvard, Sacvan Bercovitch, was another émigré, having moved to the United States from Canada. Although his own specialization was in American literature, Bercovitch nevertheless agreed to work with the young scholar from Ireland as he grappled with the ungainly edifice of commentary that had grown up around James Joyce’s Ulysses. When Duffy’s Harvard dissertation was published in 1994 under the title The Subaltern Ulysses, it drove a paradigm shift in Joyce studies, trading the conventional view of Joyce’s masterpiece as a work of cosmopolitan modernism for a new approach that brought out connections between Joyce’s formal innovations and the postcolonial struggle for Irish independence.

Looking Outward

Asked to reflect on the appeal of Irish literature to his current crop of California undergraduates, Duffy pointed to the fact that “Irishness itself is more diverse than people think.” “Ireland is like a lot of islands,” Duffy said. “Sicily, Greece, Portugal — there are these places on the margins of Europe where people have been leaving since forever. In a way I wish there were another word for it besides emigration, because there’s a stereotype of the emigrant as this poor, rural person who was essentially forced out, but there were all kinds of people who left Ireland for all kinds of reasons. Not to sound too grand, but if you look at the great writers, there’s a pattern. In going, they brought their sense of difference with them, and out of that Irish sense of difference, they manufactured even more difference. Oscar Wilde, the son of an Irish nationalist, went to England, where he invented what became the basis for modern gay culture.”

What excites Duffy about teaching is the opportunity to hear “the words of the great dead writers as they are modified in the guts of the living.” He believes that what his students learn from the Irish experience is “how to both have an ethnic identity and escape it.” Duffy believes that by “looking outward,” as the citizens of a small postcolonial island must, we can all learn to wear our pasts lightly while still developing a passionate involvement with history.

As an outgrowth of this archaeology of Irish difference, Duffy has created another popular course for the English department called Studies in Modern Literature: Literature and Life. As in his second book, which took the experience of driving at high speed as a point of departure for a series of philosophical essays about pleasure, modernism, and automobiles, Duffy uses Literature and Life to cross the boundaries that divide representation from lived experience. Above all, Duffy likes to hold out literature as “a way to think about passion.” Indy staffer Diane Mooshoolzadeh recalls that what she “loved about the Literature and Life class” was that, “in every lecture, he would tie in the theme of living a life with meaning and passion… ‘Live life more intensely.’ That’s what he would always say. We’d spend the entire quarter reading about characters and passages in novels and poems, and seeing how they lived their lives intensely and discovering what that actually means for us, and if that has changed.” Students in Literature and Life are encouraged to take chances with their final projects, which are as apt to be videos as they are to be traditional essays.

Asked about what makes him proud of Ireland today, Duffy pointed to the recent passage of the 34th amendment to the Irish constitution, commonly known as the Marriage Equality Act of 2015. Now, should they so choose, famous openly gay Irish citizens such as Colm Tóibín, author of Brooklyn, and Emma Donoghue, author of Room, can marry whom they like and have that union recognized in their home country. How’s that for living life more intensely?

Irish Lit in 2016: A Selective Reading List

While the following list barely scratches the surface of what’s available to readers interested in exploring contemporary Irish literature, it does include authors from high and low, east and west, north and south.

Sebastian Barry, On Canaan’s Side: Written in gloriously poetic prose and narrated by an 89-year-old woman, this novel traces the adventures of an émigré to America who can’t ever quite escape the political conflicts that sent her away as a young woman. Full of unexpected twists, this makes a great follow-up to Colm Tóibín’s more traditionally romantic Brooklyn, and is part of an interlinked series of novels involving a large cast of characters.

Ken Bruen, Purgatory: A Jack Taylor Novel: There’s an explosion of talent coming out of Ireland in the detective genre right now, and Bruen is a major player in that scene. His Jack Taylor series, of which this is book number 10, is full of mayhem, Galway lore, and deft literary allusions, as befits an author with a PhD in metaphysics. Bruen’s staccato, telegraphic style sometimes looks like poetry on the page, but don’t be fooled; his rhetorical moves are closer to the sweet science of the boxing ring than they are to the song forms of verse.

Colm Tóibín, Brooklyn: Tóibín, who was in Santa Barbara last spring to speak at the Museum of Art, is the dominant figure in Irish literary life today. Traveling between Dublin and New York, where he is a professor at Columbia University, Tóibín nevertheless finds the time to be tremendously prolific without losing any of the virtuosity and soul that have made him both widely respected and remarkably popular. The book on which the fine 2015 film (screenplay by Nick Hornby) is based is every bit as good as the wonderful movie, even though it may not be his best novel. Enniscorthy, Wexford, where the main character, Eilis Lacey, comes from, is also Tóibín’s hometown, and was the site of the most important Easter Rising outside of Dublin. Lacey and Farrell, the names of Eilis and her Irish suitor, are taken from the annals of the Irish Republican Brotherhood.

Emma Donoghue, Room: Donoghue was born in Dublin, but she became a Canadian citizen after joining life partner Christine Roulston and moving to London, Ontario. Donoghue is the daughter of literary critic and NYU Professor of English Denis Donoghue, and earned her PhD in English from Girton College of the University of Cambridge. Like Tóibín, Donoghue has championed gay rights in her fiction and in her life, and has become an exemplary public intellectual, effortlessly bridging the divide between academia and popular culture with a constantly growing list of publications that range from best-selling novels to plays, screenplays, and works of literary history.

Frank McGinity, Get Off Your Street: A Personal Travelogue: In this “Personal Travelogue,” now in its second edition, McGinity demonstrates just how outward-looking an Irish American (and Santa Barbaran) he is by describing the diverse and educational travels he has taken to every continent, and, yes, that includes Antarctica.

Enda Duffy, The Speed Handbook: Velocity, Pleasure, Modernism: The subtitle of Duffy’s second book is “Velocity, Pleasure, Modernism,” and there is a great deal of pleasure to be had in following the intricate argument he weaves around the modern experience of going fast. Is rocking down the highway truly “the chief thrill of leisure”? Read this and make up your own mind about the psychological impact of car culture.