From FBI Boss to Death Penalty Foe

Tom Parker's Quest to Free a Convicted Murderer

After a long career as an FBI boss, having put the Mafia behind bars, investigated dozens of homicides and sent two murderers to their deaths by lethal injection, Tom Parker became a spokesman for death penalty repeal.

Parker, a 72-year-old Santa Barbaran, is seeking the support of law enforcement officials for the Justice That Works Act, a death penalty repeal measure that qualified last month for the November ballot in California.

“There were times during my career when I would gladly have pushed the button on a murderer,” he said. “Today, my position would be, life without parole.”

During 45 years in law enforcement, Parker said, he’s seen too many corrupt homicide investigations to believe in the death penalty anymore. The worst of them, he said, is the Chino Hills murder case of 1983.

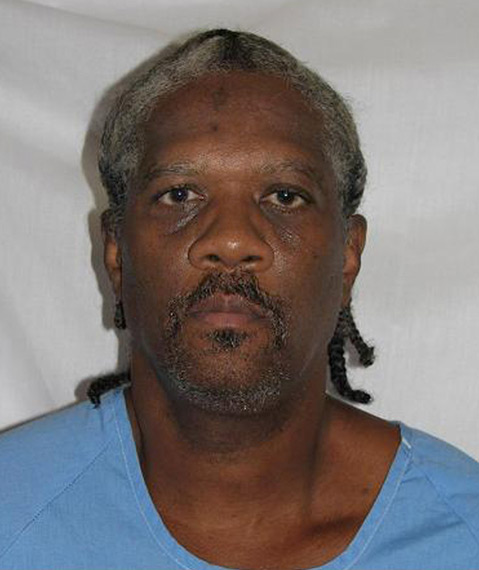

For five years, Parker has been working pro-bono as a lead investigator to free Kevin Cooper, an African-American who was convicted for killing three family members and their houseguest on June 4, 1983, in the affluent white community of Chino Hills in San Bernardino County. Cooper had escaped from a nearby minimum-security prison, where he was serving a sentence for burglary. He was arrested off Santa Cruz Island in July, 1983, and is on death row in San Quentin State Prison.

“Kevin was a car thief and a burglar, but he doesn’t deserve to be where he is,” Parker said. “I’m convinced he was framed. We arrest and convict innocent people almost every day in this country. As long as we have a death penalty in America, we will continue to execute innocent people.”

The notorious Chino Hills case, which has been featured on CNN’s “Death Row Stories,” is a flashpoint for both sides of the death penalty debate, even as it draws national and international scrutiny for alleged human rights violations. Having exhausted his court appeals, Cooper recently petitioned Gov. Jerry Brown for clemency and requested a new investigation to determine his guilt or innocence for once and for all.

California voters will confront a stark choice in the fall. The Death Penalty Reform and Savings Act, a measure to speed up executions, also has qualified for the November ballot. Michael Ramos, the district attorney for San Bernardino County and a candidate for state attorney general in 2018, is a spokesman for it. Nearly 750 prisoners are on death row in California: the last to be executed was Clarence Ray Allen, in 2006.

“Kevin Cooper is the perfect example of how dysfunctional the appellate process is and how it is being abused by those on Death Row in California,” Ramos stated on his campaign website. “He has appealed multiple times to each the California Supreme Court and the U.S. Supreme Court, and each time our case gets stronger.”

The courts have called the evidence against Cooper “overwhelming” – spots of Cooper’s blood in the Ryens’ hallway and on a tan T-shirt by the road; bloody prints of prison-issue Keds inside and outside the Ryens’ house; Cooper’s cigarette butts in the Ryens’ station wagon; and a hatchet sheath and prison uniform button at Cooper’s hideout next door.

But Cooper claims this was false evidence, planted and manipulated by the San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department to convict him. He alleges that sheriff’s deputies destroyed evidence and ignored leads pointing to three white men as the murderers – including the initial statements of the Ryens’ eight-year-old son, Josh, the sole survivor.

During a top-to-bottom review of the case for the Sacramento law firm of Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe LLP, which has been representing Cooper pro-bono since 2003, Parker concluded that the prisoner was a victim of “police tunnel vision” – that is, forcing the evidence to fit a suspect, rather than finding the suspect who fits the evidence.

“Tom really was the person who, with his background, was able to show that this was a botched and biased investigation,” said Norman Hile, the lead attorney on Cooper’s defense team. “He saw that they absolutely blew it.”

Cooper’s lawyers said that Parker has been systematically expanding the list of witnesses who saw three strangely-acting white men enter a bar near the Ryens’ home on the night of the murders, two of them wearing blood-spattered clothes.

In addition, they said, Parker has interviewed a woman who recalled driving in her grandmother’s car when it was nearly hit by a speeding station wagon with three men in it, just hours after the murders, in the suburbs of Pomona. The vehicle was identical to the Ryens’ and the license plate matched.

Parker was top FBI brass when he retired in 1994 as the assistant special agent in charge of the agency’s Los Angeles field office. He founded a consulting firm and, in 2007, moved it to Santa Barbara. Today, he is one of a small minority of former law enforcement officials who work as expert witnesses for the defense on cases involving police corruption and flawed homicide investigations.

Parker today is the only former law enforcement officer on the board of directors of Death Penalty Focus, the San Francisco-based nonprofit group that is leading the campaign for repeal in California.

Nationally and in California, public opposition to capital punishment is growing. Nineteen states have banned the death penalty. In California, a death penalty repeal initiative garnered 48 percent of the vote in 2012, compared to only 30 percent in 1977.

Parker himself began having a change of heart one day in the mid-1980s, while conducting a prison inspection in Mississippi for the FBI. He asked to see the gas chamber and sat down in the wooden chair. When the warden suddenly closed the door on him, Parker said, he was overcome by vertigo.

“That was what I call an epiphany for me,” he said. “Probably every person who sat there before me could not get up and walk away. That’s when I started re-evaluating where I stood.”

If Cooper is executed, Parker has vowed to continue working to clear the prisoner’s name.

Meanwhile, Cooper has won some support in high places. In 2009, when the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit denied his request for additional forensic testing, 11 of 27 judges publicly dissented from the opinion. Five of them signed a 100-page dissent that began, “The State of California may be about to execute an innocent man.”

Last fall, the influential Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, an autonomous organ of the Organization of American States, recommended that Cooper be granted a reprieve, pending a new investigation. Citing in part Parker’s allegations of “endemic tunnel vision,” the commission concluded that the U.S. had violated Cooper’s rights to a fair trial, due process and equality before the law. The U.S. is a signatory to the American Declaration, a treaty that guarantees those rights.

And this March, in a letter to Gov. Brown, the American Bar Association called for an executive reprieve for Cooper and a “robust review and investigation” of the case by the state Board of Parole Hearings.

The Chino Hills murders occurred on the night of June 4, 1983, when Doug and Peggy Ryen, their daughter Jessica, 10, and Christopher Hughes, 11, were attacked with a hatchet, an ice pick and either one or two knives, dying within minutes at the Ryens’ home. The two adults, both of them crack shots, had no time to grab the guns within easy reach of the bed where they were sleeping.

Two days earlier, Cooper had escaped from the Chino prison. He wandered across pastureland and holed up in a vacant house 125 yards from the Ryens’ on the nights of June 2 and June 3. He checked into a Tijuana hotel on June 5, 1983, then got a job on a boat out of Ensenada, Mexico.

The prosecution alleged that Cooper killed the Ryens in order to steal their car. (The keys were in it). But Cooper claims he never entered the Ryens’ house, did not steal their car, and was well on his way hitchhiking south at the time of the murders.

“He’s pointed out he’s an experienced car thief and could have stolen several other cars on his way,” Parker said. “He didn’t need to kill the family to steal the car.”

The defense team is closing in on the identity of the real killers, Parker said. The record shows that the Sheriff’s Department deliberately discarded a pair of bloody coveralls that were brought in a few days after the murders by a woman living in a suburb of San Bernardino. She told deputies that her boyfriend, a white man and ex-con recently out of prison, had left them at her house on the night of the crime. He was not wearing the tan T-shirt he’d had on earlier, she said. Also, his hatchet was missing.

Parker is pursuing a hypothesis that the ex-con, who had previously strangled and dismembered a 17-year-old girl, was settling a score for Clarence Ray Allen, the murderer who was executed in California in 2006. He was a member of Allen’s gang and had killed the teen-ager on his orders.

The Ryens were horse breeders and trainers. They may have sold Allen a champion Arabian and later repossessed it when he failed to pay, Parker said.

“I think I’ve found the motive,” he said.

During his FBI career, Parker initiated and ran an investigation of Las Vegas casinos in the late 1970s and early ‘80s. The probe led to the conviction and imprisonment of the entire Mafia leadership in four cities on charges of murder, profit-skimming and hidden ownership control. This was the story behind Martin Scorsese’s 1995 gangster epic, “Casino,” starring Robert De Niro and Sharon Stone.

The Mafia were a corrupt bunch, Parker said, but you don’t expect law enforcement officers to act like them.

“Police officers take an oath to protect society and administer justice on the street,” he said. “I’ve realized it doesn’t always work that way. If they won’t do what they were sworn to do, who will?”