Michael Ableman’s ‘Street Farm’ Challenges

Founder of Fairview Gardens Pens Book About Urban Farming in Vancouver

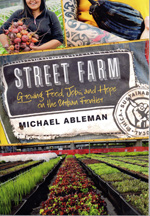

Michael Ableman has never been one to settle for low-hanging fruit. His mission to test the mettle of agriculture by cuddling it ever closer to the hearths of the urban dilemma blossomed in the decade since he left Fairview Gardens in Goleta and headed for new frontiers in Canada.

His latest book, Street Farm, begins in a vacant parking lot next to the flophouse Astoria hotel on the eastside of downtown Vancouver. He happily acknowledges the drawbacks — contaminated soils, theft, vandalism, pavement, high cost, lack of experienced skilled labor — but then he digs in. Partnering with NGOs, the city of Vancouver, and people who get things done, Ableman and crew — all employed from the neighborhood — build a fence, construct containers for imported soil, put transplants into the boxes, grow the seedlings, harvest the crop, and take it off to market. And that’s just the first chapter.

The book’s grist is HR. By the second chapter, Ableman realizes (though he must have known it from the first) that this is not good ole California farm labor. His crew is composed of those who wound up on the street for occasionally unsavory reasons, and things are getting done a whole lot slower than the economics of agriculture demand. Encouraging research on his farm by Queen’s University finds that for every dollar spent on employing people who are “hard to employ,” there is a $1.70 combined savings to the prison and legal system, as well as other sundry health, social, and environmental systems. That’s all fine but doesn’t heal a bleeding P&L. Outside funding is required.

Ableman believes in the intrinsic remedial good of farming, as do a lot of the guys in American history books. But the tasks of growing greens while grafting them onto rootstock of riskier realms of the human condition takes a toll on the enterprise. Take Rob: Big, blond, and smart, like a big moon rising amid the tomato plants, Rob is bipolar with borderline personality disorder. He “could completely withdraw,” explains Ableman. “I remember showing up one morning … and making a feeble attempt to approach him, but it was like cornering a wild animal.” Rob is also incredibly well-read and, more often than not, gets along with others. Then he falls apart. “It’s kind of shocking to see somebody unravel … because he does not wear his addiction like other people,” writes Ableman. “You don’t think someone that smart can fall to such depths.”

While the book is full of practical farming stuff, the heat generated from the underbelly of the modern city of the developed world fuels the story. “Salvation is a big idea — no one does it to you or for you. But I believe that simple things can help in profound ways,” writes Ableman. “[The farm] was built on a very simple idea: rehabilitation through meaningful work … in places where previously there was nothing but hardscape and trash and rubble.”

Street Farm is a good ride over bumpy roads, but it asks something of you in return.