The Photographer of Protest

Nell Campbell’s Photos Capture 50 Years of Demonstrations

“I’m not a big fan of the word ‘creative’,” laughed photographer Nell Campbell with a sardonic snort over a cup of coffee. “I don’t see myself in those terms.” Maybe not, but during the past 50 years, Campbell has quietly emerged as one of Santa Barbara’s best-known working photographers — simultaneously low-key and high-profile. “I see myself more as a documentary photographer.”

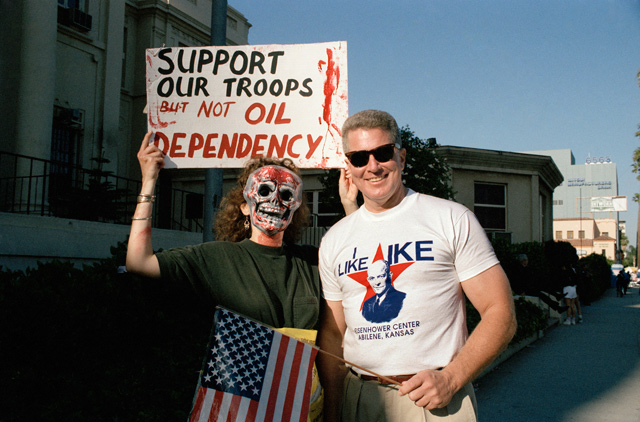

Since moving to Santa Barbara in 1969, Campbell has wound up documenting many of the demonstrations throughout the South Coast, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C. Nine months ago, with Donald Trump’s presidential ascendancy at its zenith, it occurred to Campbell maybe a refresher course on what she’d been documenting was in order. An unabashed lefty blessed with an easy-going congeniality, Campbell wondered why more people, herself included, weren’t taking to the streets. “We have this history of protesting. We might need to be doing it some more,” she said. “I guess we’ll always need to be doing it.”

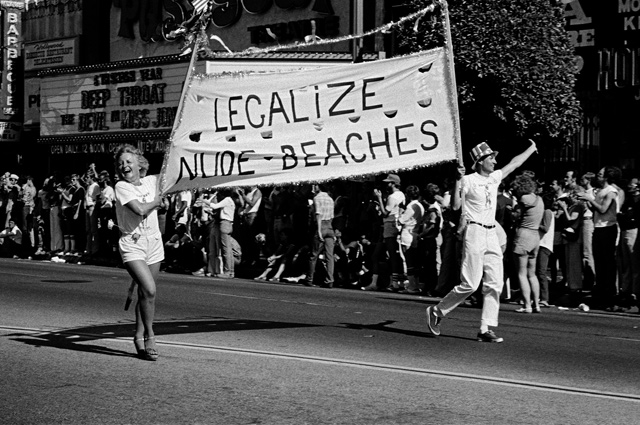

Campbell began culling through 48 years of old prints and negatives. Along the way, she stumbled onto a tsunami of protest images — demonstrations against the Vietnam and Iraq wars, AIDS, poverty, and Diablo Canyon, and for tenants’ rights, gay rights, and civil rights. She wanted to get a show up before this November’s election; a friend of hers on the board of the recently opened Community Arts Workshop (CAW) jumped in and helped make that happen. Titled Images of Dissent, Campbell’s photography exhibit opens next Thursday, November 3, at CAW and captures a half century of political protest. Her photographs — like her recollections — are detailed and journalistically precise, infused with sly wit and gentle shrewdness.

Born in Mississippi, Campbell grew up in Lake Charles, Louisiana, where her father was a doctor. She had an Instamatic as a kid and still has the photograph she took of the truck that her grandmother, whom she called Biloximamma, drove to work at the shrimp canning plant. Inspired by The Family of Man, a much-celebrated photo book of the 1950s and ’60s, Campbell realized that’s what she wanted to do, though, “I had no idea what it meant.”

On a trip to Europe in 1967, Campbell met a couple of American GIs. One had a 35-millimeter camera, and he showed her how it worked. Once she was back home, she dropped out of school, moved to New Orleans, got a job at a convenience store, and honed her craft. She’d scan the obituary pages for jazz musicians, knowing their funerals always included large, boisterous musical parades. “I’d see one of those obits, and I’d call in sick,” Campbell recalled.

In 1969, Campbell moved to Santa Barbara to attend Brooks Institute of Photography, then very much a bastion of male tradition. Of the 55 students in her class, Campbell said that only five were women. It wasn’t for her. “I knew I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life shooting perfume boxes,” she said, “which is what we were doing at Brooks.”

What was happening everywhere else was upheaval and civic protests. UCSB had emerged as a national hot spot in the student-led antiwar movement, and demonstrations routinely spilled over into the community at large. “I was against the war,” she said. “I was a participant observer. But I knew I had to document what was going on.”

Back then, Campbell had no zoom lenses; cameras were heavy and bulky. Some protesters were gun-shy about having their photos taken. As Campbell’s friend and fellow photographer Macduff Everton remembered, “There was always some guy wearing black shoes and black socks with a camera, shooting,” he said. “And you never knew whose database you’d wind up in.” But for Campbell, it was easier to shoot big crowds since people in large assemblies tend to be less aware of the camera.

To support herself, Campbell worked as a cabdriver and got involved in unsuccessful efforts to unionize the cab company. When city garbage workers went out on strike in 1976 — against the company BFI — Campbell made it a point to show up at the picket lines every morning. One day, she saw a cabdriver she’d once worked with, crossing the picket lines as a strikebreaker. She recalled tapping him on the shoulder, and before she knew what had happened, police had handcuffed her and arrested her for battery. During her subsequent trial, police officers testified that Campbell grabbed the strikebreaker and violently spun him around. The alleged victim, however, testified that had never happened. Ultimately, 10 jurors chose to believe the police, two did not, and Campbell was acquitted.

Around that time, she learned from a staff photographer for the United Farm Workers that a job was available. Campbell got hired, spending most of her time traversing California with union leader César Chávez, hitting the road at 7 a.m. and arriving at their final destinations at midnight. It was grueling work, but Campbell was committed to the cause. However, Chávez began going through some intense personal changes, seriously questioning the loyalty of many in his organization and putting them through tests that bordered on abuse. “Let’s just say that a purge was on the way,” Campbell said. She and around 30 other staffers eventually left.

Campbell moved back to Santa Barbara and continued her work as visual documentarian, while working for 12 years at the U.S. Post Office. By then she had developed a reliable knack for snatching images that told the story of an individual’s political passion. Openly lesbian, Campbell chronicled gay-pride rallies in Los Angeles and San Francisco from the 1970s to the present. During the height of the AIDS epidemic, her photo “Silence=Death,” of an anti-AIDS march in Washington, D.C., became so iconic that a publishing company stole the image to make a popular poster without her consent. Legal action ensued; she received nominal remuneration.

Not all of Campbell’s photos involved the political left. She has generated critical acclaim for her work from Cuba to Louisiana. Her photo series on duck blinds — the original man caves in a swamp-like setting — has garnered critical praise. She captured David Duke, then fresh out of the Ku Klux Klan, running for the U.S. Senate in Louisiana against Edwin Edwards, then renowned for corruption. She tracked a group of fringe Christian fundamentalists who protested Doo Dah parades, gay-pride rallies, Holocaust museum openings, and Hare Krishna gatherings with equal evangelical outrage. She laughs about capturing a photo of the ringleader as he happened to stand right behind a horse’s ass.

Stylistically, Campbell adheres to a strictly no-frills credo. She shoots most things, she said, in a very straight-ahead, direct manner. With portraits, she joked, “I find some nice light and put them [her subjects] under it.” In those sessions, she described her approach as “bossy but not threatening,” adding, “Mostly, I tell people how great they’re looking and not what they need to do.”

Photographer Macduff Everton put it somewhat differently. “Her style is to tell the story of the person she’s shooting; it’s not something she imposes on that person.” Everton said he’s frequently asked by younger photographers how they can make money in their chosen field. His advice is simple. “Don’t photograph gay-rights demonstrations, antiwar demonstrations, grape-boycott demonstrations,” he stated. “Nell puts in the time, the passion, and the thought to tell the story and to get it right. I think that is the definition of an artist. You do something because you have a compelling need to.” But it goes beyond self-indulgence. “People who resort to demonstrations usually feel they aren’t being heard. By documenting them, Nell keeps their voice alive.”

4•1•1

Nell Campbell’s photography exhibit Images of Dissent opens 1st Thursday, November 3, and shows Friday-Saturday, November 11-12, at the Community Arts Workshop (631 Garden St.). An artist reception will be held Saturday, November 5, 4-7 p.m., with an artist’s talk by Campbell at 4:30 p.m. For more information, call 682-6148 or visit sbcaw.org.