‘Puccinality’ at UCSB College of Creative Studies

‘The Handmade Life of Fran and Keith Puccinelli’

One of the many benefits of having love in your life is the permission it can grant to be yourself. When graphic designer Keith Puccinelli reached a crossroads in the late 1990s, his wife, Frances Garvin Puccinelli, said he should leave commercial work and devote himself completely to creating fine art. In the process of emerging from cancer treatment, Puccinelli invented a tragicomic persona — the wildly cartoonish and decrepit clown Pucinello — and produced both brilliant large-panel drawings and several performance-art installations that many regard as the most significant such work done in Santa Barbara. At the same time that all this was going on, Fran was transforming Linden Avenue through a series of small business ventures — a deli, a coffee place, and a gallery — and boosting the whole town of Carpinteria by creating the Avocado Festival.

Puccinality: The Handmade Life of Fran and Keith Puccinelli, a new exhibit at UCSB’s College of Creative Studies Art Gallery, reflects both the tragic loss of Fran Puccinelli to complications of Parkinson’s in late 2016 and the curatorial team’s desire to celebrate the couple’s exemplary partnership in art and in life. Between the two of them, Fran and Keith Puccinelli have had a lasting impact on the region, and co-curators Dane Goodman, Meg Linton, and Dan Connally felt that the time was right to introduce the public to the parallel world they created for themselves, a place of “puccinality,” that ineffable quality that ties their making, their collecting, their aesthetic, and their senses of humor together. Although Keith Puccinelli has had solo shows at the SBCC Atkinson Gallery and the Ben Maltz Gallery of the Otis College of Art and Design in recent years, it’s only with Puccinality that those outside their circle of friends are getting to see what an extraordinary life the couple created in their own home.

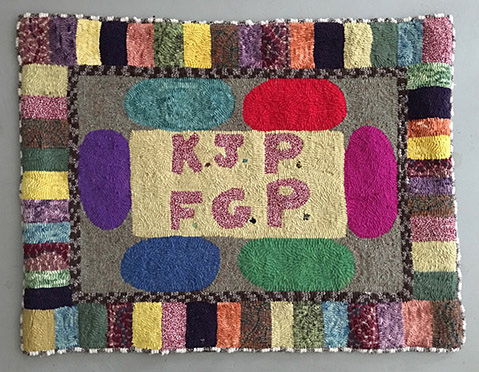

Using a mix of Fran and Keith’s own work, objects from their large collection of folk and outsider art, and handmade furniture from their home, the curators have assembled an unforgettable expression of their shared sensibility. For example, there are more than a dozen splendid examples of Fran’s clever and homely hooked rugs. These deceptively humble affairs typically employ a palette that would serve as camouflage in a thrift store, yet the more you look at them, the more there is to see.

Keith’s contributions cover the breadth of his obsessions both temporary and permanent. There are cruelly curving, suspiciously twig-like crutches in a corner over by a great painting by American folk artist Howard Finster, and there’s an entire long shelf filled with oversized, slightly clunky flashlights constructed out of cardboard tubes, masking tape, and a finish that Keith refers to as “faux papier-mâché.” While these constructions and some of the others, such as the flaming toaster and the flaming shorts, may appear casually tossed off, it’s unlikely that’s the case. As is apparent from many of the other pieces, like a spectacular door intricately inlaid with individually burned matchsticks, there are untold hours of the artist’s attention lurking in virtually every detail. This becomes particularly clear when looking closely at the magnificent panel drawings, which were made in pieces and over the course of many hours using a quiver of fine pointed Japanese pens. The overall impact of this excellent show is, fittingly, twofold. There’s the sense that we are looking at the very best fine art produced in this region and that these two people really loved one another. I can’t think of a better combination.