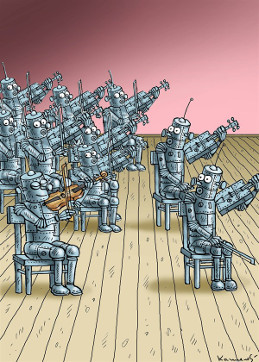

What Is Your Automation Policy, Mr. President?

A 'Bot May Be a More Potent Job-Killer than Free Trade or Immigration

President Donald Trump frequently and enthusiastically painted free trade and immigration as American job killers during last year’s election campaign, but both Trump and challenger Hillary Clinton barely mentioned one of the most serious threats to employment that we face: automation. From current factory displacements to future technology innovations, we can expect major changes to job and work patterns in the next two decades due to artificial intelligence and robotics, with experts predicting that automation could claim up to half of all existing jobs.

Although proponents are right that automation can have a positive impact on the economy by freeing up workers to perform new and different roles — as we have seen throughout history — the scale and pace of future displacements at all income levels suggest that this time might be different. New jobs created by automation might not pay as well, retraining is costly, and many people might not succeed in finding a job of any kind.

President Trump’s speech to Congress last month did not mention automation, but as he shapes his agenda for the coming years, addressing these uncertainties with robust policy action will ensure that technological advances benefit all Americans and the economy as a whole.

Recent calls for policy action, to raise taxes, curb corporate stock buybacks, and expand social care are an excellent start. But at a time when President Trump and congressional Republicans want to slash taxes and regulations, and reduce the size of the public sector, such proposals will face strong opposition.

Automation also creates new and difficult challenges that require careful foresight and planning — things that our current policy-making structures have historically failed to deliver well.

For example, some have suggested shortening the work week, or raising wages, but recent labor trends run counter to these ambitions, and both solutions further incentivize automation and threaten jobs.

One frequently cited solution to full-scale automation is to offer a “basic income” to all Americans regardless of income status. But even a modest figure of $10,000 per year for America’s 150 million workers suddenly becomes prohibitively expensive, at upward of $1.5 trillion, or 40 percent of the U.S. budget.

Alternately, policy-makers could provide a basic income only to those who need it, but this creates a disincentive to work which runs counter to our recent history of welfare politics.

There is also the impact of automation on consumer spending and the economy. If workers have less earned income, economic growth could fall dramatically as businesses see their traditional customer base erode.

Lastly, we might decide that keeping humans in some jobs could provide certain social benefits, such as retaining cultural heritage or offering a higher quality of interaction.

Teachers, for example, might deliver better learning outcomes for children than exclusively automated education. People might prefer human carers and shop assistants to robot counterparts, and we might decide that humans, particularly the young, gain invaluable self-confidence and self-esteem from working, despite the fact that a robot could perform a task more efficiently.

Unfortunately, we currently lack any formal process for addressing these and other important questions spurred by new technology.

Although the Obama administration began to explore these issues in reports issued last year, Trump administration officials must take the next steps to protect the American worker — by appointing an expert commission or reviewing options for comprehensive policy action, ideally with broad public input.

The worst thing we could do is leave automation to the market, since it will likely result in either widespread inequality or, more likely, a political backlash so potent that it blocks the future progress of the technology.

As Harvard economist Lawrence Katz told the New York Times last year: “Just allowing the private market to automate without any support is a recipe for blaming immigrants and trade and other things, even when it’s the long impact of technology.”

Unchecked automation will lead to a world that is either less stable or less fair — and possibly both.

It is time for a more balanced and realistic discussion of automation, rather than dismissing it as a dystopian job killer or extolling it as a harmless panacea — both views are overly simplistic and wrong-headed. Automation is a tool, and its future is what we make of it.

President Trump has a unique opportunity to shape a public debate that grows louder each day.

Rather than stoking misplaced fear and naïve optimism, we must start the conversation about how robots can lead to a happy ending.

Barney McManigal is a London-based writer who taught political science at Oxford University and served as a policy adviser in the U.K. Department of Energy and Climate Change.