Advocating Sound Science for Pesticides

EPA's Pruitt Should Listen to His Scientists: Chlorpyrifos Is Bad for Humans

Every so often, political appointees surprise us by standing up to special interests and making scientifically sound decisions that put the health and safety of the public and the environment first.

Spoiler alert: we are not going to be talking about one of those cases.

In the final days of March, while most of us were more invested in our NCAA brackets than federal environmental policy, the newly appointed head of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Scott Pruitt, announced that the agency would not be banning a toxic pesticide linked to human and environmental health complications. Chlorpyrifos (don’t worry — we have to sound it out, too – klor-piri-foss) is a pesticide intended to kill insects on contact by disrupting critical brain function. Though it has been banned from household use in the United States since 2001, chlorpyrifos is still widely applied on agricultural lands nationwide.

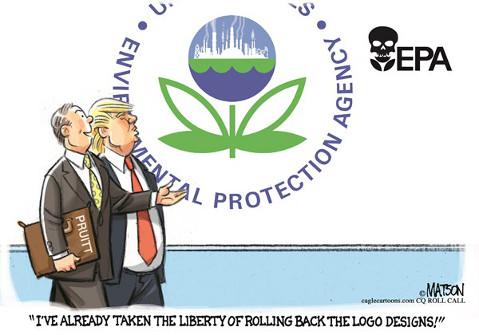

In 2015, the EPA — the same EPA that Pruitt now heads — moved to permanently ban the pesticide following an assessment that found risk to humans through dietary and drinking water exposure. But Pruitt’s announcement last month retracts this action in an effort to “provide regulatory certainty to the thousands of American farms that rely on chlorpyrifos” and return to “using sound science in decision-making — rather than predetermined results.”

Pruitt’s argument that sound science should serve as the foundation of our environmental policy is absolutely correct. Unfortunately, his actions do not match his words. The decision to withdraw the chlorpyrifos ban appears to be rooted more in political promises to reduce regulation than legitimate scientific evidence.

You see, the science around chlorpyrifos is sound. There is no shortage of studies linking chlorpyrifos exposure to human health effects, such as lower birthweight, tremor, and other neurodevelopment problems in children. And when it comes to its environmental impact, studies showing the pesticide’s effects on other species and their habitats are downright abundant.

An EPA assessment of chlorpyrifos’s potential biological effects evaluated more than 1,400 studies on its toxicity to various plants and animals that are either endangered, threatened, or candidates for listing under the Endangered Species Act. The results of the assessment are alarming to say the least, showing that chlorpyrifos is likely to negatively affect nearly 97 percent of the species evaluated. That includes 91 species of birds, 188 species of fish, and 87 species of mammals.

Amphibians have been particularly hard hit. Recent amphibian population declines have prompted numerous studies attempting to determine a cause, and pesticide exposure is one leading hypothesis.

Take, for example, a 2009 study on tiger salamanders, a relatively common amphibian found throughout central North America. Researchers found chlorpyrifos exposure reduced survival and made larvae more susceptible to viral infection. Or how about the study in which researchers with the U.S. Geological Survey found lower brain functioning and higher chlorpyrifos concentrations in Pacific treefrog tadpoles sampled from Sequoia National Park compared to those from other parts of California.

Perhaps you are questioning why relatively pristine ecosystems like those in the Eastern Sierras appear to be showing more problems from chlorpyrifos than other, more polluted parts of the state. If so, then you’ve picked up on a key problem with pesticides: They rarely stay put.

Much of the 1.45 million pounds of active ingredient chlorpyrifos applied annually in California is used in the agriculturally intensive Central Valley, but summer winds blow chemicals eastward, putting many of the beautiful natural areas we Californians love in harm’s way.

So, what’s the solution? How do we balance the need for food security with environmental stewardship? The answer probably includes a diversified approach that mixes different agricultural management strategies. This may even include some pesticide use, but we should be responsibly using the pesticides we believe to be safe and eliminating those we know to be damaging.

Our reactionary “spray first, think later” national pesticide policy has let us down in the past (anyone remember DDT?), and we share Pruitt’s desire for a change toward decision-making grounded in sound science. That starts by listening to scientists, including those at the EPA, who have already agreed: Chlorpyrifos simply isn’t worth the risk.

John Sisser and Matt Gargiulo are master’s degree candidates at UC Santa Barbara’s Bren School of Environmental Science and Management, specializing in Pollution Prevention and Remediation. Sisser also specializes in Water Resources Management.