Oil Spill Lessons

A Refugio Retrospective, Two Years After

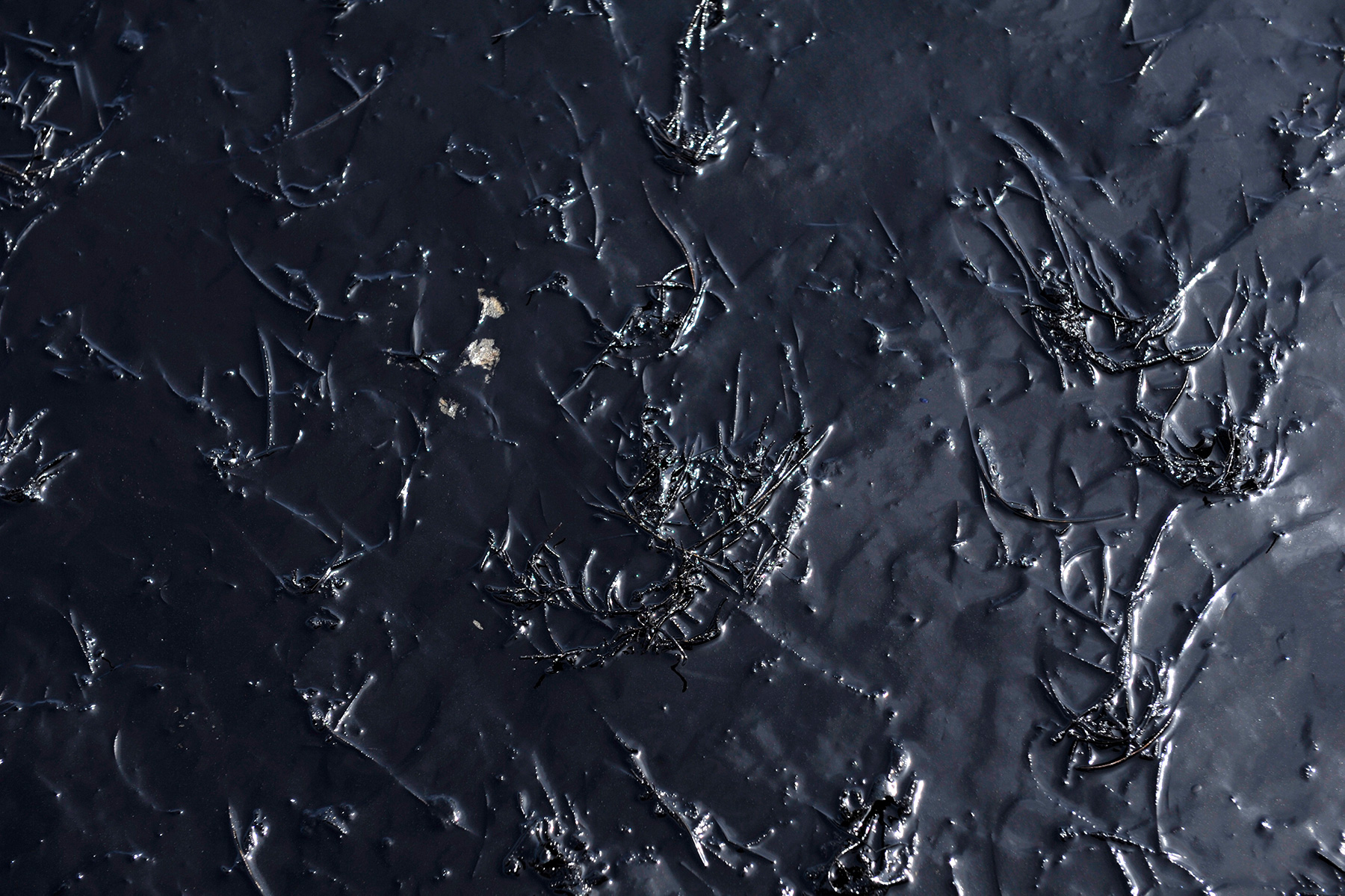

Two years after the Refugio Oil Spill, county supervisors are still second-guessing the emergency response they thought could have spared the state beach from 142,000 gallons of crude oil. They pointed to several ways cleanup vessels could have worked faster and more efficiently.

Framing the discussion was a healthy dose of party politics. First out of the gate, Peter Adam, arch-conservative county supervisor, complained the board had already discussed the incident ad nauseam. He argued the oil spilled in the 2015 incident was a tiny fraction of that in Santa Barbara’s infamous 1969 spill. County Supervisor Das Williams, an outspoken environmentalist who worked on state legislation to enhance emergency oil response, objected: “If this small of a spill could create this much damage, what would happen to our community with a catastrophically large spill?” County Supervisor Janet Wolf, who headed response efforts, added, “It was a nightmare. The impact was huge.”

The exchange perfectly embodied the polarization of oil drilling in Santa Barbara. While North County conservatives say oil drilling provides necessary revenues for strapped county coffers, the environmental community on the South Coast has become increasingly hostile to any new drilling.

Environmentalists appear highly critical of onshore operations at Cat Canyon, an oil field near Orcutt. Last fall, facing strong opposition, the county supervisors denied the Pacific Coast Energy Company’s proposal of roughly 100 cyclic steaming wells. The county’s Energy Division currently has 700 pending cyclic steaming well applications. Given the strong environmental leanings of the board majority, the fate of those operations appears increasingly slim.

In addition, the ruptured pipeline, Line 901, operated by Plains All American Pipeline, remains shut down without a proposal submitted to federal regulators to restart operations. Currently, the 24-inch pipe is entirely emptied and filled with inert gas. A Plains representative did not attend Tuesday’s hearing, but a representative with the federal regulatory agency Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration said the massive interstate company has given no indication of how it plans to proceed. Plains could replace the entire pipeline by installing internal sleeves and replacing places where it ruptured.

The fact that Line 901 has been inoperable for two years has had significantly negative effects on area oil companies, namely Venoco. The relatively small company recently announced it would decommission Platform Holly after hurting financially for years. Low oil prices exacerbated the company’s struggle.

One positive that came out of the spill, officials said, was that the Office of Spill Prevention and Response updated its contract so vessels with Clean Seas could get to the scene faster. Linda Krop, chief counsel at the Environmental Defense Center (EDC), said another positive outcome of the incident was the greater role county officials would play in the next response. During the incident, there was some criticism that the U.S. Coast Guard stepped on the toes of local authorities, who had a better sense of the area. The county’s updated oil spill contingency plan should be completed at the end of 2017.

Andy Caldwell, a conservative watchdog, said the enviros could cry all they wanted, but the reality was the county has lost millions in tax dollars. Those exact numbers, though, remain squishy. He added, “I think we should have someone here from Plains to have their side of the facts.” Caldwell expressed some satisfaction there was some mention of the theory that natural oil seeps have been enhanced by less oil drilling. “Pollution is pollution whether it comes from a pipeline or Mother Earth,” he said.

While Republicans appeared eager to move on, environmentalists said the public remains greatly interested in Line 901. Owen Bailey, the executive director of the EDC, said, “My request is that you schedule another briefing six months down the road.”