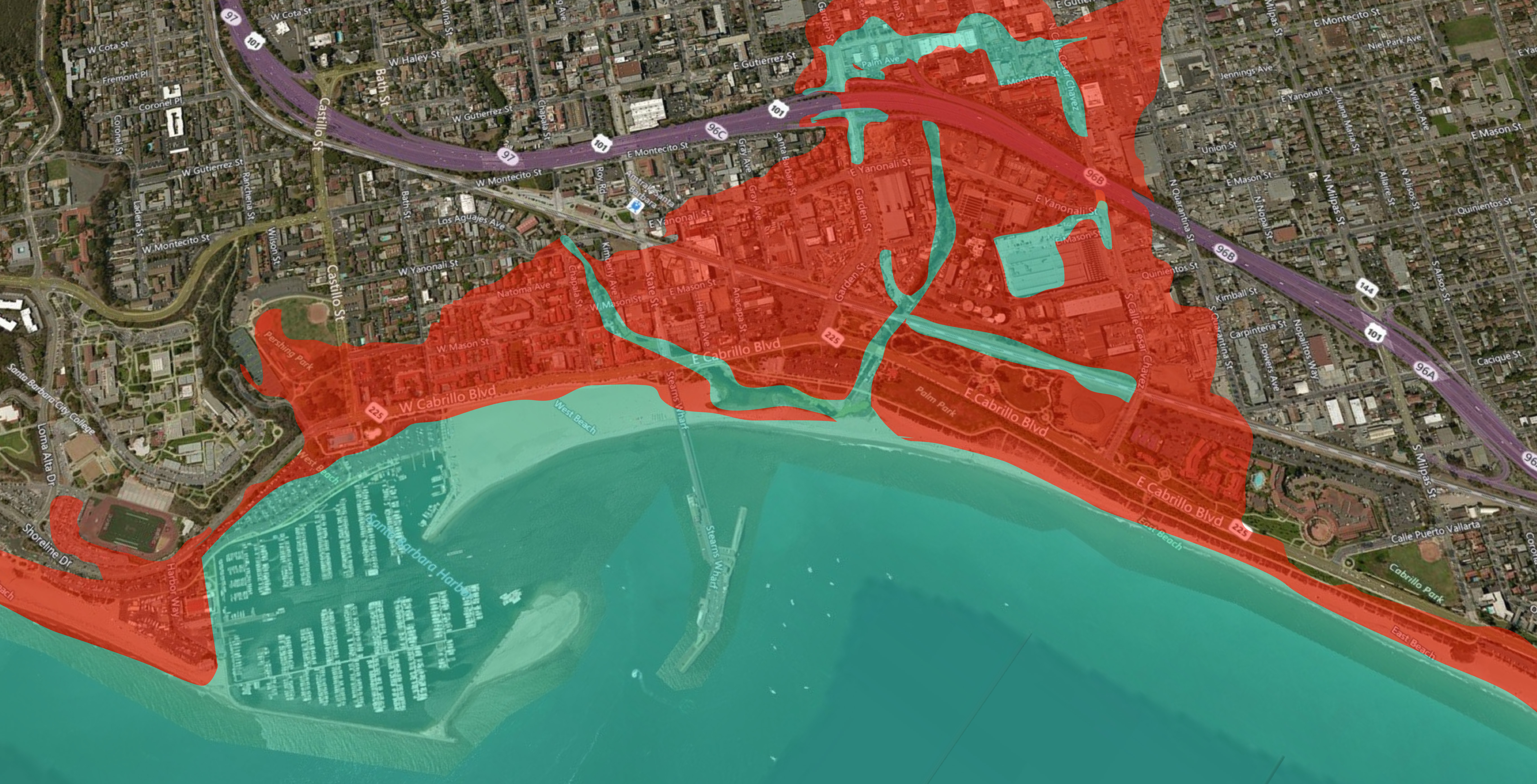

of flooding. Red portions represent 55 inches by 2100, plus three feet of flooding. Maps like this use the “bathtub approach” — assuming that everything below a specific elevation will be inundated — and do not factor in natural or man-made barriers.

Santa Barbarans are a varied bunch, but there’s one thing we’d probably all agree on: We like our coastline where it is.

Rising sea levels, though, mean that our beachfront — and quite possibly our downtown — will be fundamentally changed over time. And a new report issued in April found that sea level rise along the California coastline could be faster and more drastic than previously predicted. Especially alarming was one scenario that saw California experiencing a 10-foot sea level rise by 2100, higher than most scientists previously thought possible. Regional sea level studies, of course, can be tricky. It’s difficult to accurately assess how one community will be impacted.

So while the authors don’t know how likely such an extreme scenario is, they can confidently predict it would be a fairly remote possibility. More certain are the report’s projected middle-of-the road scenarios, which look similar to what we knew already. What we know already, however, is cause for concern.

Gary Griggs, a UC Santa Cruz oceanographer who studied the Santa Barbara coastline in 2012 and found the city vulnerable to climate-caused sea level rise, also contributed to the new April report, commissioned by the California Ocean Protection Council. Griggs has a personal interest in Santa Barbara — he went to UCSB as an undergraduate and has two daughters in the area — one a former Santa Barbara Independent staffer. He estimates the city will likely see a 12-inch sea level rise by 2050, and three to four feet by 2100. (That’s assuming we continue curbing our carbon emissions.)

But here’s the good news: There’s a lot we can do. The April report clearly shows that our future is in our hands. The rate of sea level rise before 2050 is essentially fixed. But if the world manages to get its emissions under control and achieves the kinds of goals outlined by the Paris Accord, the most likely outcomes for 2100, while significant, are pretty livable.

Antarctic Chill

According to the new report, California’s sea level will be particularly affected by the melting of the West Antarctic ice sheet, which is happening at a faster rate than anticipated. This is particularly bad news for the state, since Antarctic Ocean currents move in our direction.

Over time, the state’s sea levels will rise more quickly than the world average, according to the report. One contributor, Bob Kopp, a Rutgers-based climate scientist, said the research group decided to include extreme scenarios, such as a rise of 10 feet by 2100, “even though it’s hard at the moment to figure out how likely they are.” He explained that scientists are just beginning to understand what ice-sheet melting will look like in the future: “We’re getting a better hold on our ignorance.” Though climate scientists want to be as impartial and accurate as possible, they all agree that sea level rise is taking place at a worrying rate, even if there’s some dispute about precisely how much.

Sea levels have always changed over long periods. They began to level off about 8,000 years ago, allowing humans to begin forming agrarian communities. That means, on a global scale, rapid sea level rise “may be the biggest challenge civilization has ever had to face,” Griggs said. “There’s nothing we can do [to stop it]. We can only respond to it.”

Coastal Views

Santa Barbara’s coastline is already at risk from a laundry list of environmental issues: flooding, tsunamis, infrastructure damage, cliff erosion, shrinking beaches. Local ecosystems, like the Carpinteria Salt Marsh and the diverse kelp forest in the Channel, are also jeopardized. Accelerated sea level rise threatens to intensify these problems.

The 2012 study, which Griggs conducted with graduate student Nicole Russell, found that the shape of Santa Barbara coastline would likely change over time, with beaches narrowing or even being submerged. Even 14 inches of sea level rise could reach Shoreline Drive.

But the bigger threats, according to that study, will actually come from temporary events: high tides, large waves, storm surges. This will cause more frequent flooding in low-lying areas such as the Andrée Clark Bird Refuge and the airport and could turn into the “perfect storm” when combined with sea level rises during an El Niño year.

And predicting the effect that rising tides will have on Santa Barbara’s stretch of coastline is particularly challenging. We don’t have a great history of tracking tide levels, for one thing. To make matters more complicated, plate tectonics are pushing the Santa Barbara coastline upward, according to UCSB oceanographer Alexander Simms — although the sloughs in Carpinteria and Goleta are sinking at the same time. We’re also experiencing temporarily lower levels right now due to a repeating fluctuation in the Pacific Ocean’s climate. When the ocean atmosphere shifts again, sea levels will rise.

Neither plate tectonics nor atmospheric shifts are enough to cancel out sea level rise, but Simms stresses this is still good news. It means Santa Barbara’s waters are rising more slowly than in other parts of the world — the global rate is about 3 mm overall; the local coastline between 0.8 and 1.25 mm. That’s likely to increase substantially over time.

No matter what, the atmosphere has warmed enough that melting ice sheets will contribute significantly to the volume of ocean water. Griggs compares it to dropping an ice cube into a boiling a pot of water: You can take the pot off the heat, but it still won’t be a hospitable environment for the ice cube.

A Sanctuary Coast

The scientists interviewed for this article all agreed that Trump’s decision to withdraw from the Paris Accord is a significant step backward. “There’s no way to soft-serve this one. It’s a real loss,” said David Lea, a UCSB oceanographer who wasn’t involved in the report. “Honestly, this decision moves the likelihood of the most extreme scenarios up.”

But as Representative Salud Carbajal recently pointed out, state and local efforts to reduce emissions are well underway. (Earlier this month, the City of Santa Barbara committed to having 100 percent sustainable energy by 2030, and California agreed a few weeks ago to work with China on reducing emissions, to name just a couple of examples.) Carbajal also noted that any number of federal agencies and programs are still working to address climate-change issues. “Things don’t come to a stop just because this president says ‘stop,’” he said. “There’s still a framework … that transcends what a president or administration can do.”

According to Rutgers scientist Bob Kopp, when scientists talk about how “business as usual” can’t go on, they’re talking about unchecked, continually growing emissions — what we were headed toward before the world began to take organized action against climate change. Recent research actually suggests that emissions rates, while mostly still on the rise, are starting to slow, in large part due to the declining use of coal.

In the midst of a high-alarm culture, Lea has been a consistent voice for a moderate, non-sensationalist approach toward climate science. And he has one piece of advice: Don’t give up. “I don’t believe there’s a red line,” he said firmly. “Even if we get to 2 degrees [Celsius of global warming], even if we get to 3 … we always want to try to limit emissions.”