When Machine Learning Isn’t Smart

Basic Safety Questions Remain as We Race into an Artificial Intelligence Future

Big tech companies have had a tough year in PR, after being accused of distorting elections, automating jobs, fueling mental illness, and avoiding taxes. But they may face an even bigger challenge in a disruption still to come — ambitious plans to develop a fully fledged and autonomous machine intelligence, a safety risk some observers compare to nuclear weapons.

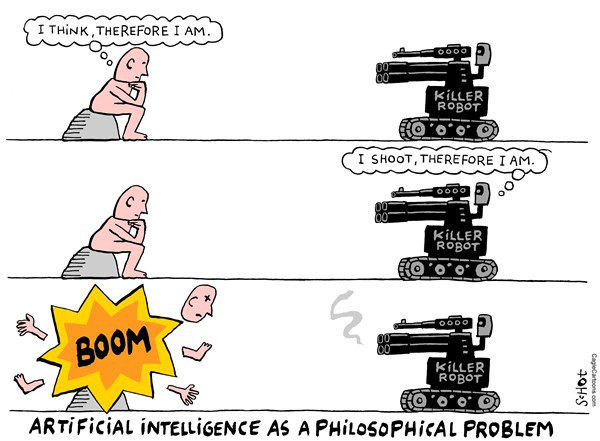

Killer robots are not exactly banging down the door, but entirely unregulated developments in artificial intelligence (AI) should give even the savviest early adopter pause, since these innovations bring us closer to a much-discussed but still unresolved policy problem: How will machines created to exceed human intelligence remain accountable to their creators?

Today, AI is mostly limited to software algorithms that can perform an increasing number of high- and low-skill tasks with moderate success. But Google, Facebook, and untold others are racing ahead to develop the data-absorbing “neural networks” of machine learning that designers hope will yield a machine intelligence capable of mimicking or surpassing human cognition.

Yes, it’s a big leap, and it might take decades, but you don’t have to be a self-hating human to fear a machine that takes after us. Microsoft proved this much last year, when its Twitter “chatbot” Tay, designed to learn from other users, ended up espousing racist and violent abuse online. Even more troubling are software programs — currently in use to sift job applications, evaluate workers, and police criminality — which apparently reflect discriminatory biases in their algorithms.

As we are seeing, machines that learn from humans will often act like us, too.

Recognising a potential existential safety threat, some practitioners hope to build operational controls into any AI system. However, with humans in control it’s difficult to see how such a machine would be truly “smart.”

Another widely discussed option is to provide an “off switch” for all systems. However, giving a broad swath of humans the ability to disengage each and every robot could place any commercial activities supported by AI systems at serious risk.

Moreover, couldn’t a truly intelligent machine capable of learning on its own simply prevent or reverse its own shutdown?

Some observers say our best hope of protection from the machines we create is to merge with them. This includes Elon Musk, the AI-supporting Tesla CEO who has raised high-profile safety concerns recently, including as a petitioner for a global ban on autonomous weapons. Other AI supporters hold out hope that intelligent machines might coexist peacefully with humans.

Of course, merging with a machine or hoping a super-intelligent robot doesn’t kill you is not what most people sign up for when they purchase the latest smart phone app, legal software, or myriad digital products that use sophisticated algorithms.

This is exactly the point: Our scattershot public discussion bears little resemblance to the dramatic impact (good and bad) that AI systems could have on our lives, jobs, privacy, health and safety.

We hear frequently about the benefits of future AI — interventions ranging from the recreational (sex bots) to the life-saving (cancer treatments). In Santa Barbara County, farmers could one day dispatch teams of robots to plow, plant, and pick their way through the region’s many arable acres — and dramatically reduce labor costs.

We hear much less about the risks. If artificial intelligence is an existential threat comparable to nuclear weapons, shouldn’t we at least begin the policy conversation?

Some say the best course of action when facing a serious threat is not to create such a danger in the first place — the so-called precautionary principle. Others are more sanguine, particularly those who hope to profit commercially from innovation.

Yet we are moving ahead without answering the safety question, and even AI enthusiasts are worried.

President Trump has shown little interest in addressing the issue. And in the U.K., where I live, politicians facing the economically bleak prospect of leaving the European Union have shown more interest in the financial gains of AI than discussing risks.

This much-needed policy debate seems unlikely to occur anytime soon because governments typically delay action on new technology until something goes terribly wrong.

Or perhaps the politics of our unregulated AI sector will create its own response, the same way that unchecked inequality, free trade, and automation contributed to Britain’s economically punitive Brexit and Donald Trump’s unlikely victory.

Either way we lose.

Barney McManigal, a former Santa Barbaran, is currently a U.K.-based researcher specializing in technology governance. He taught political science at Oxford University and served as a policy adviser in the U.K. Department of Energy and Climate Change.