Land of the Talking Dead

Santa Barbara Spiritualism Then and Now

at the end of the 19th century.

In September 2017, the University Club in Santa Barbara hosted an event in the lecture series Anthropology Straight Up on “Psychics, Mediums, and Shamans.” For Kohanya Groff the large audience was no surprise. As founder and CEO of BOAS Network (“BOAS” stands for “Broadening Anthropology’s Spectrum” and also recalls Franz Boas, the Columbia University professor who is considered the father of American anthropology), a nonprofit organization dedicated to providing a forum for anthropology entertainment, information, and education, she knows that shamans sell. What would come as a surprise to anyone expecting the typical academic, hands-off approach to the subject was the presence of a second speaker on the bill, Tony Morris, an executive with a different area nonprofit who identifies as a psychic medium. For a fee of $140 per hour, Morris works with his clients by meditating about them in order to access information, much of it concerning the future, that he claims comes from “the other side.”

Put the two together, and you have the potential for conflict. Groff, who earned her PhD in anthropology at UC Riverside studying Chumash shamans and neo-shamans, necessarily has a sharp eye for inconsistencies and mixed messages in the origin stories of self-proclaimed Native American mystics. Neo-shamans are those who have not been trained by a traditional shaman or any member of an indigenous American culture, but rather rely on books and experimentation to achieve their sense of their own psychic status.

In this case, however, the two form an unlikely truce, as Groff the anthropologist extends Morris the psychic medium something like the benefit of the doubt in her talk. For his part, Morris relishes the opportunity to describe his process next to someone from the scientific community who understands that various kinds of shamanism have existed at many times and in many places throughout recorded history, and will no doubt continue.

Round one of the conversation, which can be seen in its entirety on the BOAS website, was, to this observer at least, inconclusive. What did appear to me, without the aid of a crystal ball, was the opportunity to look more closely at a phenomenon that has piqued the interest of many Santa Barbara residents over the years: the affinity between spiritualist beliefs and our city. Spiritualism, defined as a system of belief or religious practice based on supposed communication with the spirits of the dead, especially through mediums, has a long and rich history here. By looking back at the period in which these beliefs first flourished here, it may be possible to gain some insight into their persistence.

Cheap Homes for Worn-Out Mediums

On September 24, 1892, Henry Lafayette Williams, former paymaster general of the Union Army and the owner of the Ortega Rancho in what is now Montecito and Summerland, addressed a public letter to the spiritualists of the world announcing that the “undoubted and immense resources of the Ortega Rancho” would henceforth be dedicated to “the promulgation of the truths of spiritualism.” Williams’s proclamation must have been met with relief by at least some members of the burgeoning new church founded on the notion that it was possible to communicate with the dead.

The Church of Spiritualism had suffered a seemingly definitive blow to its credibility just four years earlier, when, on October 21, 1888, Margaret Fox, one of the two founding mediums of the movement, took the stage at New York’s Academy of Music and admitted that all the spirit communication claims she and her family had made for the last 40 years were fraudulent. According to Fox, when she and her sister Kate summoned the spirits of the dead by asking them to knock, “one for yes, two for no,” and proceeded to use this knocking code to “converse” with them, the sounds were not coming from the other side of death but from the inside of her shoes. The trick that had taken in tens of thousands was in fact remarkable, not as evidence of the afterlife but rather as evidence of an unusual talent. To make the sound of the spirits knocking, the sisters cracked the joints in their toes. Their toe-popping talent was such that the unamplified sound of Margaret’s crackling feet that night easily reached the rear of the farthest section of the Academy of Music, a theater near New York’s Union Square with a capacity of 4,600.

Undeterred by the public confession of Margaret Fox, Spiritualists continued, and indeed continue to this day, to claim the Fox sisters as founding figures in their church, which operates as an organized religion without Christian affiliation and comes complete with tax-exempt status and an official symbol, the sunflower. Summerland, as is widely known, was named after the imagined location of the afterlife within which the spirits contacted by Spiritualists reside. Liberty Hall in Summerland was torn down to make way for the 101 freeway, but since then the aura of supernatural doings, or at least the reputation for such an aura, has clung to the Big Yellow House, a structure clearly visible from the freeway that marks the approach to Montecito and Santa Barbara from the south.

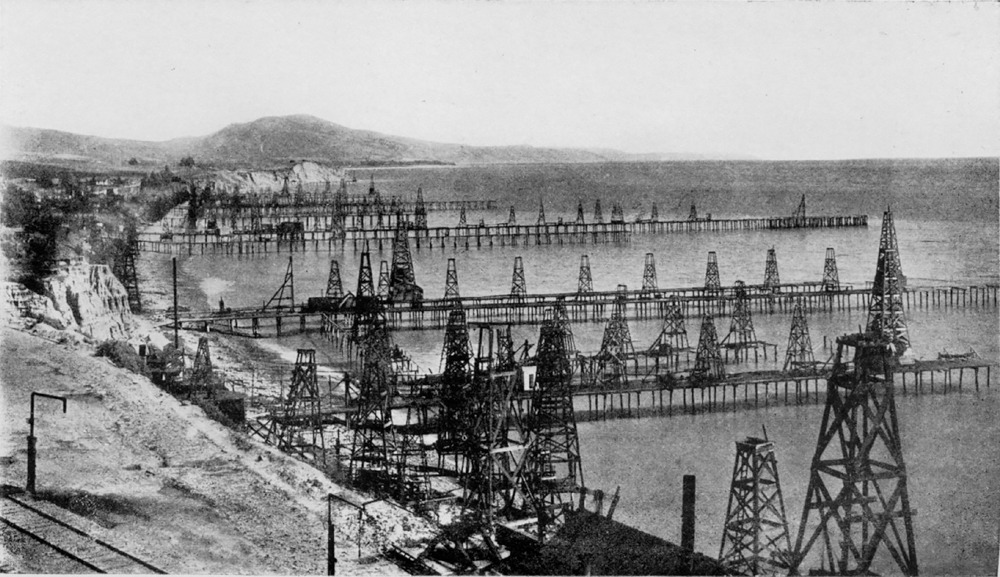

Why would Summerland founder H.L. Williams, a veteran of the Civil War and a former high official in the United States Treasury department, build a community supporting the work of a discredited movement? Fortunately, Williams provided clues to the explanation later in the same sentence in which he dedicates Summerland to Spiritualism. In addition to promulgating the truths of Spiritualism, the land of the Ortega Rancho, or at least a portion of it located near the newly arrived train tracks of the Southern Pacific Rail, would be devoted to “aid in building cheap homes for Spiritualists” and “homes for worn-out mediums.” Did Williams have the distraught and penniless alcoholic Margaret Fox in mind when he wrote that last phrase about “worn-out mediums”? We will never know, but what we do know is that Williams knew a good thing when he saw it and wasted no time switching agendas when it suited his business interests. The next thing that took his fancy proved to be the far more lucrative black magic of fossil fuels, which were discovered (first natural gas, and then oil) under the land and seabed off Summerland in such shallow pockets that the entire city could be illuminated by torches simply by pounding a pipe far enough into the ground and lighting the top.

Magicians Oppose Psychics

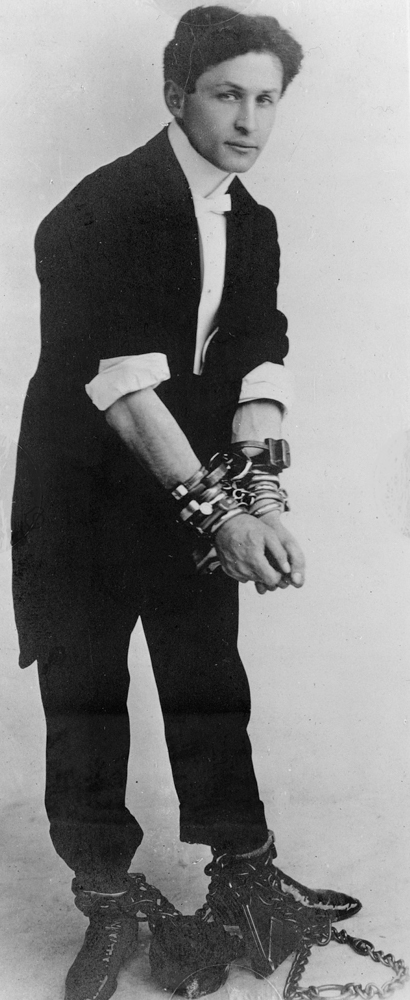

At the same time that H.L. Williams was finding a soft place in his heart — and a sweet spot on his ranch — for tired mediums and their followers, a very public battle raged over the legitimacy of psychic mediums, who were at a peak in popularity at the turn of the 20th century. The disputants were both famous men, and their respective positions on the subject reflect a perhaps surprising and unquestionably ongoing split. In one corner stood Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the esteemed author of the Sherlock Holmes detective stories, and in the other was Harry Houdini, the world-famous escape artist. What’s intriguing about the men’s engagement with the issue of spiritualism is that the creator of the greatest symbol of empirical deduction in all of fiction, Sherlock Holmes, happened to harbor an inexhaustible appetite for seances, spirit talking, and all forms of mediumship, regardless of their ability to withstand scrutiny. On the other side, Houdini, presumably master of all sorts of techniques of dissimulation, was utterly impatient with what he saw as a massive fraud perpetrated by con artists on an unsuspecting and vulnerable public. In part as a result of their personal disagreement, Houdini conducted public sessions for unmasking psychics’ claims; the dispute eventually led to the end of the two men’s longstanding friendship.

For evidence of the skepticism that stage magicians and mentalist entertainers still harbor in regard to psychic mediums, I had to go no further than (voila!) Summerland, where Maurice Lord, a five-time Indy Award–winning theater director and practicing magician has lived for decades without seeing a single spirit … and not for lack of looking. A magician member of The Magic Castle in Los Angeles and an avid student of the paranormal, Lord, like Houdini, has no time for psychics, viewing them as “sloppy, unprofessional mentalists preying on vulnerable people.”

Thanks to a technique called “cold reading” and a set of procedures designed to minimize distracting false hits and encourage subjects to comply with the reading process, a well-trained mentalist can put even stalwart nonbelievers into a state of confusion in a matter of minutes. Having attended several of Lord’s mentalism performances, which he holds from time to time for invited audiences at the McDermott-Crockett Mortuary, I can attest that his self-confessed magic tricks are the only events I encountered in the course of researching this piece that I still cannot explain to my own satisfaction. His mentalism shows are truly dazzling — and a lot of fun — but Lord insists that they are entertainment and do not represent real evidence of things unseen.

As a mentalist entertainer, he insists on staying as far as possible from claims of special psychic powers. “For me that would completely ruin it,” he said. “If after a show someone came up to me and wanted help in contacting a dead relative, I’d be depressed. There are mysteries in the universe, and there are ways of exploring them, but this isn’t one of them.”

Professional wrestlers have a word for the unspoken agreement they share not to drop character, no matter what. It’s called “kayfabe,” “the fact or convention of presenting staged performances as genuine or authentic,” and psychic mediums and magicians both observe it, albeit with diametrically opposed intentions. Among magicians, it is common to admit that the basis for any given performance lies in a concealed illusion, and the kayfabe contract is that no good magician ever reveals how those illusions work to the audience. You can see this convention observed weekly by Penn and Teller on the popular television program Fool Us. At the end of each performance, Penn and Teller confer and sometimes even examine the performer’s props while the host conducts an interview. When they are ready, the duo either congratulate the performer for fooling them, and thus winning a spot opening their show in Las Vegas, or they inform the artist that they believe they know how the trick was done. At that point, they may show the performer a written note to see if they are correct, but more often than not they simply let Teller do his thing, which is to say nothing at all.

You Get What You Need

When it came time for me to test the waters with a reading of my own, I entered into it feeling relatively carefree, which may not have been such a good thing, at least for the purposes of psychic mediumship. I met with Morris and paid him his standard fee in cash, and he proceeded to let it rip, psychic-style. An hour later, after listening to his soft Alabama accent as he unveiled a series of things he had seen in his psychic mind’s eye through a process that involved some preparatory meditation, a single card drawn from a modern tarot deck, and a handful of in-the-moment visitations that Morris marked with the classic medium’s mid-temple finger massage and earnest squinting, I remained cheerfully entertained without experiencing any significant change in my skepticism. Morris has style, he clearly cares for his clients, and he strives for transparency as far as he can, but there are places that a psychic medium’s clients simply cannot go, such as inside the spiritual medium’s head.

Without the option of falsifying what a medium says he or she “sees,” the subject is left to negotiate the vast and shapeless terrain of resemblance, relevance, and recognition. The standard formulation of the psychic — “Why am I seeing X?” — leaves the client responsible for making the ultimate connection between whatever the medium says and some aspect of reality. For me, entering into the relationship without the urgency of personal matters that so many people clearly bring to it, there were “hits” — points at which what I was hearing did in fact resemble some aspect of my life — but they were no more compelling as psychic revelations than they would have been as daydreams or points of departure in a standard getting-to-know-someone conversation. If, in coming weeks, the most obscure aspects of my reading suddenly attain unexpected importance in my life, I’ll be the first to admit it.

As a client of a psychic medium, one enters into a specific type of conversation that is both enabled and constrained by unspoken rules, and one of them — perhaps the most important — is that you must arrive needing or wanting something. Perhaps I violated this, spiritualism’s first commandment, “Thou shall want something from the reading.” All I was looking for was a story to tell, and maybe that’s just not enough of a desire to get spirit sparks to fly.

From one perspective, this is bad news for psychic mediums. How can you expect to receive recognition and validation for claims that can’t be demonstrated to work regardless of the client’s mindset? From another point of view, however, I got what I deserved. It was a case of the experimenter’s fallacy, in which expectations overdetermine the interpretation of the results. Although it’s possible that I could have gone into the experience with a more open mind, in the end I feel like “open” isn’t exactly the word for how my mind would have had to be for my experiment with spiritualism to succeed.

Anthropology could contribute here, as could the perspective supplied by those knowledgeable skeptics who practice the illusion of mentalism as entertainment. Americans today profess faith in a broad range of dubious claims and often refuse to consider the weight of significant empirical evidence. With psychic phenomena, as with other claims that violate norms around what’s acceptable as real, it’s reasonable to seek explanations that comprehend not only the absence of evidence, but also the presence of those needs and desires that provide the soil in which such beliefs can grow.

4•1•1

Anthropology Straight Up continues on Tuesday, September 11, 5-7 p.m., at the University Club of Santa Barbara (1332 Santa Barbara St.). Kohanya Groff will lead a discussion on “The Afterlife” featuring Tony Morris and Peter Wright, a certified hypnotherapist specializing in past-life regressions. For further information about the Anthropology Straight Up series, visit boasnetwork.com. Maurice Lord performs feats of magic and mentalism at the McDermott-Crockett & Associates Mortuary (2020 Chapala St.). To receive an invitation to his next performance, email him at themaurie@gmail.com.