A Soldier’s Letter Home

Recalling World War I in Belgium and France

On a trip to France in early October, I began to notice the war memorials, particularly those for World War I. Every village and town throughout the country has one, many with the names of those who gave their lives etched on them. I saw them in the countryside, in small parks, and on city streets.

I noticed them particularly because of letters my grandfather, Stuart Wilson, wrote. My grandfather, a Canadian by birth and the child of Irish/Scottish immigrants, volunteered for the Canadian Expeditionary Forces in May 1915. By August, he was in the trenches of Ypres, Belgium, in a machine gun battalion. And in the summer and fall of 1916, he was again in Belgium and in France in the Somme.

He was hospitalized several times, with undisclosed injuries, and by 1917 he was stationed at a camp in Seaford, England, where he remained until after the end of the war, that is, after the Armistice, the agreement struck between the warring parties to cease hostilities on November 11, 1918.

I know all of this because he wrote dozens of letters and postcards home to his wife and two daughters, children who were two and four years old when he went overseas. Luckily, my grandmother saved them all. I did not visit the places where he fought (except online), but for me, I don’t think visiting the old battlefields would have brought his experiences of the war as vividly to life as have the dozens of postcards and letters he wrote home.

My wife, Isabel, and I stayed overnight in one town, Chateaubriant, on the way to Azay le Rideau in the Loire Valley. Our hotel was situated on as street named rue du 11 novembre, a telling memorial in itself, since it was the 11th hour, of the 11th day, of the 11th month of 1918 that the war was declared to come to an end.

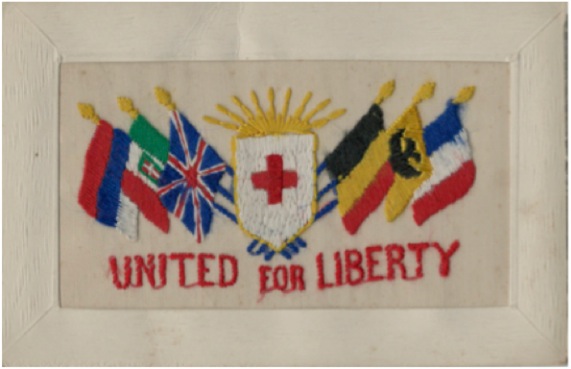

What struck me, and what must strike every visitor to France — apart from visits to the chateaux of the Loire Valley and the museums of Paris — was the absolute carnage that occurred during this Great War, which was thought, wrongly, the war to end all wars. We can compare the magnitude of this carnage to our own Civil War and Revolutionary War and get a sense of the loss of lives. With a difference: It was an alliance of many nations against Germany, as the flags on the embroidered postcard my grandfather sent home attest.

My grandfather was a soldier in a machine gun regiment. Toward the end of the war, he was promoted from private to corporal. In one of his cards to his daughters in late 1918, he said, modestly, “this may not mean much to you, but I’m a Corporal now.”

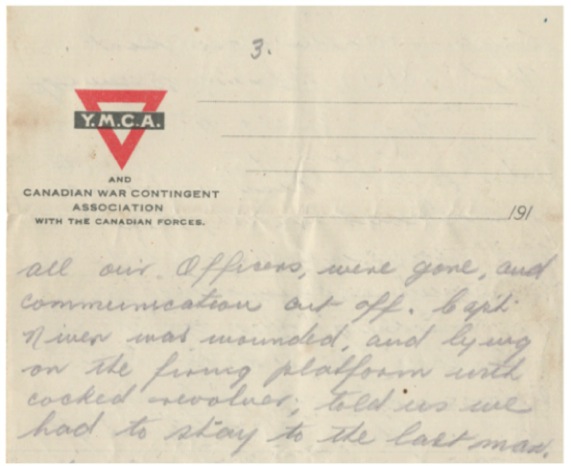

He wrote in great detail of his experiences. One letter in particular recounts his harrowing experience in the battle over Mount Sorrel near Ypres on June 2, 1916. That was a 10-page letter home, dated June 6-8, when he was out of harm’s way, after the remnants of his decimated regiment were ordered finally to retreat. I include a section below to give a sense of the look of the letter, the stationery he used, in this case, with the YMCA imprint, and his handwriting in pencil.

He wrote: “All our officers were gone, and communication cut off. Capt. Niven was wounded, and lying on the firing platform with cocked revolver; told us we had to stay to the last man.” The image of Captain Niven, described in the letter, lying wounded with a cocked revolver, ordering his men to stay to the last man, is terrifying. At the battle of Mount Sorrel, Canadian troops suffered 8,430 casualties. Visitors today can pay homage at the Hill 62 (Mount Sorrel) Canadian Memorial, near Ypres. My grandfather was one of the few lucky ones to get out alive.

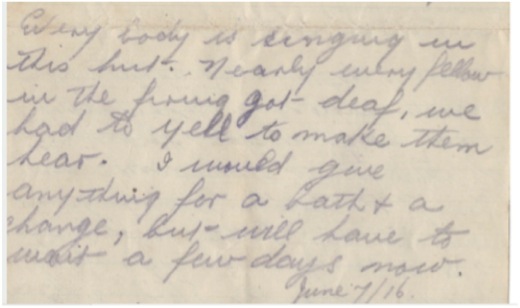

A few pages on he wrote about their successful retreat: “Every body is singing in this hut. Nearly every fellow in the firing got deaf, we had to yell to make them hear. I would give anything for a bath and a change, but will have to wait a few days now.”

It is perhaps hard to imagine what it is like to go without a bath and a change of clothes for weeks on end. Singing was no doubt a way of expressing their collective relief from being out of harm’s way. The Canadians were known to bring their pipes into the fields of battle.

Now well removed from the firing lines, he continued: “we are away back at a farm now. Marched for six hours on the cobblestone roads. I had a good bed last night. Lots of clean straw and three blankets, the best bed I have had in nearly three months. This country is very pretty; everything is so green. It is all groves of tall trees.“

The terror of the battle and the fear that the end was near gave way to the sheer joy at being away from the fighting, away from the sounds of shelling and artillery and his fallen comrades. A few days later, on June 8, he expresses his thanks for small comforts of the farm, a bed and blankets.

Later that summer, he went on to the Somme where even greater loss of life occurred. It is hard to imagine, especially for someone who did not serve in combat, the day-to-day hardship the ordinary soldier suffers, but a sense of humor must have helped him, as this photo he sent home suggests.

It seems fitting now for me, and for us, to remember not only our grandfathers and great-grandfathers and -mothers, but also all of the soldiers who served in past wars on this the 100th anniversary of the Armistice, and to say: “I am thinking of you.”