Cops or Crops at Cota Lot?

Santa Barbara City Council Poised to Make Major Decision on Downtown Dispute

This Tuesday, the Santa Barbara City Council will decide whether to move forward with a controversial plan to build a new police station at the Cota Street Commuter Lot, the current home of the Saturday morning Farmers’ Market.

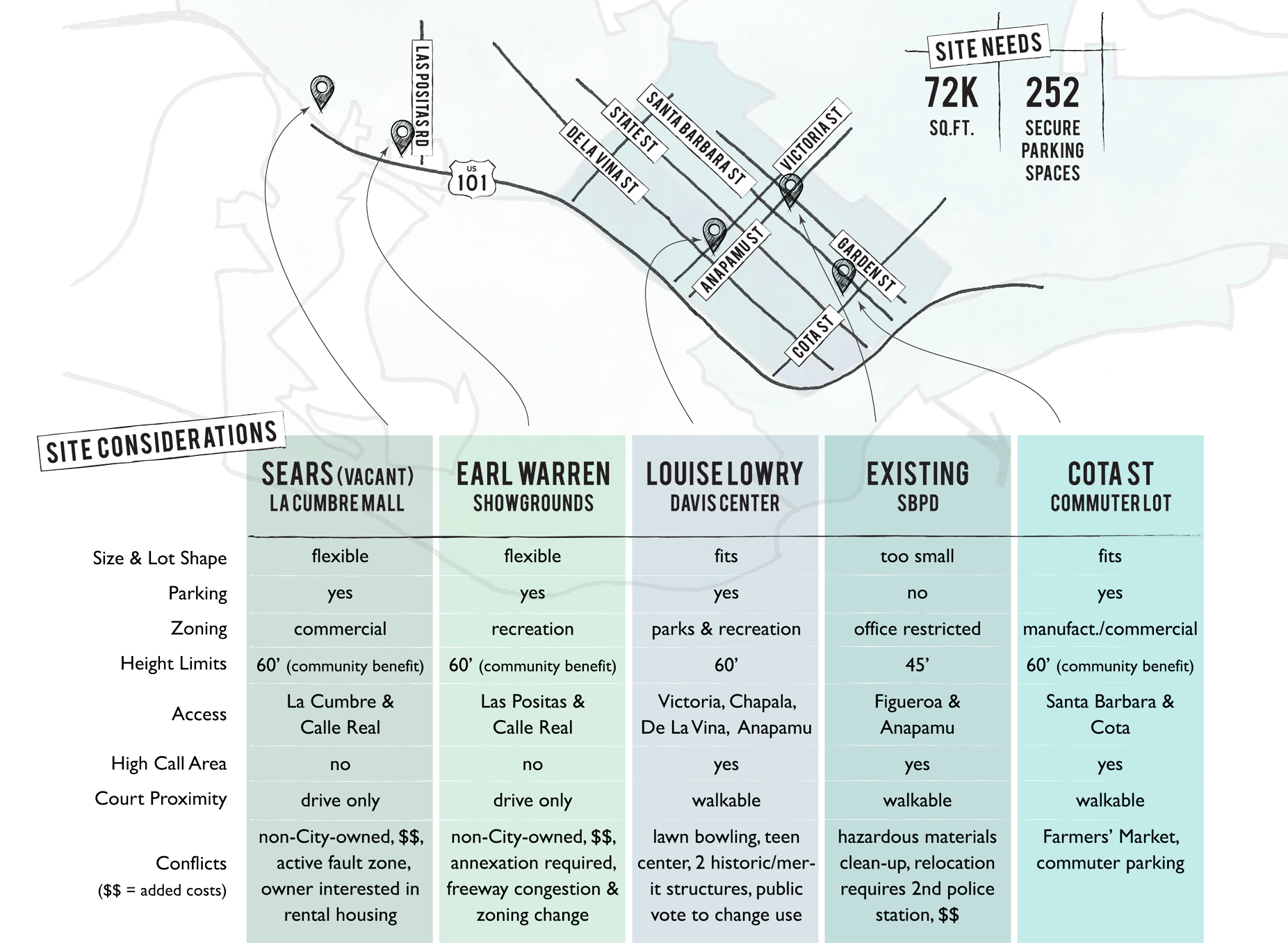

Over the past year, city staff have studied more than a dozen possible locations for the new station and narrowed it down to five top contenders. (See the accompanying graphic.) They insist the Cota lot is the best option, and they’ve suggested De la Guerra Plaza — which is scheduled to receive a major makeover — as the strongest alternative for the market.

The farmers, however, are loath to relocate and say the plaza doesn’t fit their needs. Despite intense negotiations on both sides, Santa Barbara is facing its own no-deal Brexit scenario. Tuesday’s vote will determine how future talks play out.

The Farmers

Noey Turk, president of the Farmers’ Market board, operates Yes Yes Nursery in the Santa Ynez Valley, which grows cooking and medicinal herbs, vegetables, and native plants. Like the other 110 small family farmers in her association, Turk depends on the Saturday market; it supplies nearly half of her yearly income. “We couldn’t survive without it,” she said. Farmers have always run on tight margins, Turk said, and with regional pressures now building — longer droughts, higher land costs, industrial competition, and the steady creep of cannabis crops — the last thing Santa Barbara growers need is a sudden upheaval from their longtime home.

Turk and her cohorts worry if their new headquarters is too inconveniently located in terms of parking and access, customers will buy less or stop coming altogether. And the large Saturday market is the lynchpin of the entire Farmers’ Market organization, Turk explained. The other five weekly events are smaller and rely on its revenues to stay afloat. “If the Saturday market goes down, the whole system goes down,” she said, calling the choice between sustained farming or better policing an unfair one. “Public safety and food security should never be put at odds with one another,” she said.

Sam Edelman, the Market’s general manager, called the Saturday gathering the “heart of the city,” where 3,000-5,000 people come to shop. It’s not some quaint get-together, he emphasized, and requires a serious amount of equipment and coordination to distribute its 20 tons of food. Edelman has voiced concern over whether De La Guerra Plaza, which is slightly smaller than the Cota lot, could accommodate a fleet of trucks moving in and out, or the tables, canopies, and other equipment necessary for operation. Perhaps even more importantly, Turk noted, Saturday’s market is an incubator for budding farmers just getting their start. And there’s room to grow. Moving to De La Guerra Plaza would mean putting a moratorium on new members, she said. “That would be really unfortunate.”

Last month, County Supervisor Joan Hartmann, whose 3rd District includes dozens of small farmers, sent a letter to the council urging it to consider “the long-term economic viability” of the market. On Tuesday, Turk said her group will present the council with a 7,000-signature petition that asks the Cota Street lot be designated the association’s permanent weekend home. She said that’s not too much to ask. “It’s common for cities to provide space for a farmers’ market,” she said. “And many cities do more than that.” Turk encouraged residents to attend the meeting and show their support. There will be food, she said.

The Police

Police Chief Lori Luhnow insisted a new station isn’t a matter of convenience, but one of necessity — and urgency. “We’re really behind the 8-ball on this,” she said. “Every day we wait, I worry it will have an impact on public safety.” The department has completely outgrown its current headquarters, Luhnow explained, and it’s a seismic nightmare. “If we had a major earthquake and the building collapsed, the city would be in serious trouble,” she said.

The Figueroa Street station was originally built in 1959 to accommodate 85 people. The department has since expanded to 220. There aren’t enough bathrooms for the 22 female officers, cramped interview rooms are situated too close to witness areas, and for a while, the forensics technician operated out of a janitor’s closet. Two weeks ago, Luhnow said, a water pipe broke in the briefing room and spilled water on a new recruit’s head.

Moreover, the department is spread over four locations — its main building, nearby office space rented for $200,000 a month, the dispatch center in the Granada Garage, and Animal Control behind Fire Station 3 on Sola Street. “We’re super disjointed operationally,” Luhnow said. “Things don’t flow.” The Cota option would bring the entire department under one roof and dramatically increase efficiency, she said. And it would leave officers within walking distance of the courthouse to testify, which may seem like a trivial matter but is actually a major factor, Luhnow explained, given how often they’re called to the stand. Plus, it’s critically important that the station remains downtown, where the majority of calls for service originate.

Project Manager Brad Hess insisted the city can simultaneously build a new station and maintain a vibrant farmers’ market. “This isn’t an either/or situation,” he said. Hess promised that if the council moves ahead with the Cota lot and the farmers have to relocate, he and his staff will do everything in their power to facilitate the transition. “As much as they want us to understand how big of a deal this is for them, we want them to understand how willing we are to help,” he said. “But they have to trust us.”

Hess noted that the city Farmers’ Market first started at the Mission, then moved to Santa Barbara High School before settling into its Cota digs 35 years ago. He said he was confident it would survive another move if necessary. Hess disputed the argument that there’s less parking around De La Guerra Plaza than there is around Cota, pointing to Lot 10 across from Antioch, the Paseo Nuevo lot, the Lobero lot, and the school district space. “There’s actually twice as much parking,” he said.

While City Hall thinks the plaza is likely the best alternative for the market, Hess emphasized staff isn’t trying to tell the farmers what to do. “We’re just saying to them, ‘What do you think?’ ” And while it’s not technically the city’s responsibility to find them a new home — “We’re the landlord and they’re the tenant,” he explained — it recognizes the importance of the market and so wants to partner on a solution that works for everyone. Sam Edelman, the market’s general manager, has been invited to sit on the plaza’s revitalization committee.

Hess estimated it would cost $15-20 million for the city to buy a brand-new piece of downtown property, a daunting proposition given the estimated $80 million-plus it will take to just build the station. And that’s assuming the city could find a private landowner willing to sell. No one has come forward with an offer, he said, and the parcels he did look at were simply too small. The elephant not in the room is Wendy McCaw, whose News-Press building would suit many of the new station’s needs. But so far, she hasn’t shown any interest in helping.

Hess said adaptability would be built into the new station, wherever it ends up, to accommodate the ever-evolving needs of public safety, which might mean the use of more community policing, drones, or some other strategy that hasn’t even been thought up yet. The project’s technical architect — MWL Architects, based in Phoenix — is the national authority on police station construction with more than 300 designs under its belt.

Hess estimated even if the council votes in favor of the Cota lot on Tuesday, it would be two years before construction began and the market would have to move. “Yes, it hurts,” Hess said, empathizing with the farmers who’ve sat in limbo the past year waiting for a final decision. “It’s a tough choice, but at some point, you have to pick your battle.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.