The Shifting Winds of Fire Management

California Has Two Fire Problems, and They’re Very Different

The American West is getting hotter and drier, and that has driven a quick succession of ever-more-devastating wildfires. Clearly, we need to examine our approach to fire risk management.

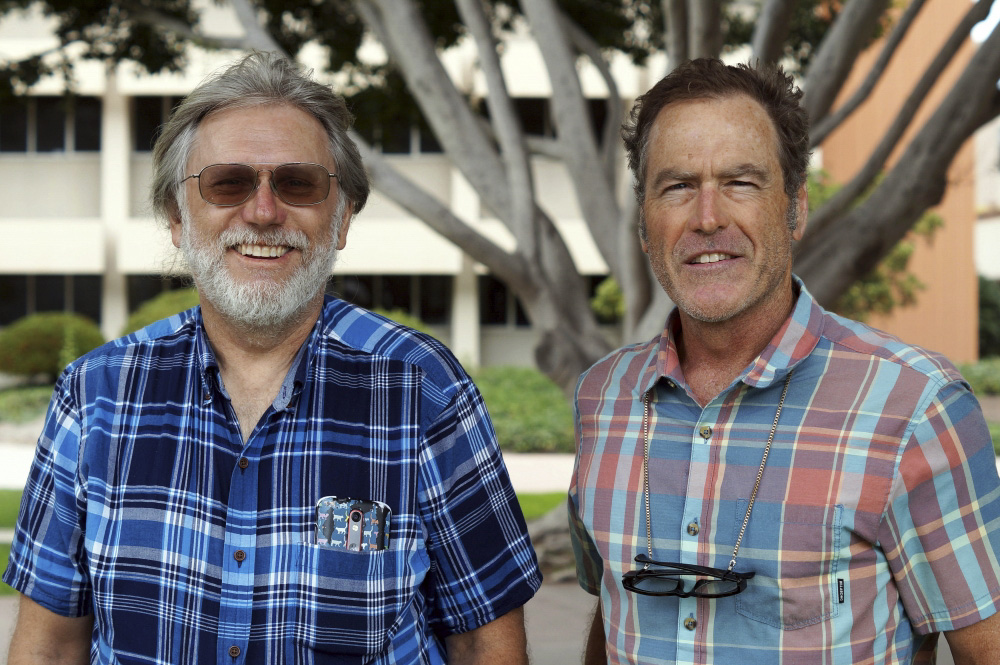

It’s a complicated matter made more so, researchers say, because politicians and the public tend to conflate two rather different issues. “We are mixing up the problem of forest and fuel management with the problem of wildland-urban interface fires,” explained Max Moritz, an adjunct professor at UCSB’s Bren School of Environmental Management and a statewide Cooperative Extension wildfire specialist.

Forest management often focuses on controlling the distribution of fuels, explained geography professor Dar Roberts, who serves as UCSB’s principal investigator of the Southern California Wildfire Hazard Center. For instance, he said, fire agencies create fire breaks and conduct prescribed burns.

But those techniques don’t apply to neighborhoods and homes. The issues are not even closely related, but academics have had a difficult time communicating this to the public. “It’s a huge part of why we’re actually not making much progress toward solving that wildland-urban interface problem,” said Moritz, “because that’s a problem of where and how we’ve built our communities.”

Changing Our Communities

California sets building codes in an attempt to ensure that structures are safe, sturdy, and resilient. However, the state does not have similar codes at the community level. And according to Moritz, most of the solutions to wildland-urban interface fires lie in city planning. “You can lay out a community in a way that’s much safer: buffered, easier to evacuate, easier to defend,” he said.

For instance, developers often build houses along a perimeter road with backyards adjacent to the surrounding landscape. Planners could designate this land for irrigated parks or community gardens, which would provide a buffer zone between the community and the wildlands. The road would then serve as a firebreak, further insulating the neighborhood. “All those ideas are in people’s heads, but they’re not codified into a consistent set of best practices that apply from county to county and city to city,” said Moritz.

The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, also known as CalFire, does provide some higher-level suggestions, but they are mostly limited to roads, water, and fuel management. The state also issues fire hazard maps, but how those are utilized at the local level varies, Moritz said.

City planners and firefighters often have to contend with buildings and communities already in place. But there are many ways to harden an existing structure against wildfire. Some are intuitive, like maintaining a brush- and debris-free perimeter around a house. Tile roofs also increase fire resistance, especially if the gaps between them are covered to prevent embers from blowing underneath.

Other improvements are less apparent. “Another really easy way to better defend a house is double-paned glass,” said Roberts. Glass is fairly opaque to thermal radiation, so a double-pane window provides twice as much shielding. The air between the two panes also offers insulation. “Given sufficient time, that window will melt,” said Roberts, “but fires often go through [a neighborhood] pretty fast, and so it doesn’t take that much to prevent the house from blowing up from the inside.”

Sometimes, the best course of action is to leave things the way they are. For instance, orchards are different from natural vegetation because they’re irrigated and green. “In Santa Barbara, the best thing we could do is preserve our orchards,” said Roberts, “because in any place we have an orchard, it actually acts as a defensible barrier against fire spread.”

Staying Safe

When it comes to evacuation plans, the primary strategy in the U.S. is to get out. Unfortunately, with these large, fast-moving fires, some people aren’t leaving in time — or don’t have enough time to escape. “That’s a big part of what we saw up north this year,” said Moritz. “Lots of people leaving too late and either dying in their cars or having to get out of their cars and run.”

Both Roberts and Moritz hope that California will continue to provide early evacuation warnings. The researchers also agree that we should consider additional strategies, such as the use of local fire shelters (much like tornado shelters), which could protect individuals who find themselves outpaced by the flames.

The practice of sheltering in place is so common in Australia that the country has an associated saying: “Prepare, Stay and Defend, or Leave Early.” This strategy has now begun to emerge in the U.S. For instance, Pepperdine University in Malibu told students to shelter in place during the November 2018 Woolsey fire, since the school’s concrete buildings and well-watered lawns were unlikely to burn.

“The question is, do we want to advocate shelter-in-place?” said Moritz. “Most firefighters do not because it’s a lot of liability for them. They want to get this message really clear: ‘When we tell you to go, you go.’ And there’s no gray area here.

“But there is a gray area,” he said, “because what if people don’t get the message in time?” We don’t have an education campaign or a plan for this unfortunate and quite deadly possibility, he added.

Australia has also revamped its evacuation protocols since the Black Saturday bushfires of 2009, which claimed 173 lives. “Now there doesn’t even have to be a fire for them to trigger an evacuation,” said Moritz — the potential danger of a particularly hot, dry, windy day can prompt an evacuation order. California may do well adopting a similarly cautious approach, Roberts and Moritz suggested.

You Can Only Manage So Much

Out in the wild, management works only up to a point. “Fires are behaving in ways that many of these agencies have not experienced before,” said Roberts. “Under extreme weather conditions, the best management in the forests is probably not going to be good enough.”

Different ecosystems also have different fire regimes. Yellowstone’s lodgepole pine forests have adapted to immense conflagrations that strip the landscape once every few centuries. Much of the California chaparral, on the other hand, has evolved to cope with fires sweeping through every 30 to 60 years. Many plants even require fire at some point in their lifecycles. “We want fire in those systems doing the kind of work that they’re adapted to,” said Moritz.

Large fires can occur in surprisingly rapid succession under severe weather or drought conditions. “Under extreme conditions, it only takes maybe two or three years of recovery before a fire can easily spread through an older scar,” said Roberts. This leaves the landscape vulnerable to invasive grasses, which can go up in flame on a yearly cycle. “It’s a positive feedback loop,” added Moritz. Other fires are driven by accumulated fuel. For these, a thick layer of dry underbrush from decades of fire suppression can lead to an inferno.

Under extreme conditions, however, fires just burn everything in their paths, added Roberts. Higher average temperatures, prolonged droughts, and lower humidity are all contributing to the region’s growing problem. “Given that there’s going to be big fires, and there’s likely going to be no way to prevent them from happening, what we need to do is figure out ways to minimize damage,” said Roberts. “We have to adapt.”

This is an edited version of a story originally published in The Current, UCSB’s official news site, on October 25. Read the full version at news.ucsb.edu.