The Continuing Battle for Voting Rights

Archie Allen Recalls Marching with John Lewis

Sixty-one years ago, Archie Allen had flanked a 20-something John Lewis on the front lines of the civil rights movement, challenging Southern segregation and securing voting rights for Black Americans. Much has changed since the Santa Barbara chiropractor picketed in lockstep with the future congressmember — legislation to expand voting access has been blocked in the Senate to this day. Nonetheless, Allen, while disappointed, remains optimistic as he witnesses a new generation of activists take up the fight for an equitable democracy.

Growing up in western Virginia, the son of a Methodist minister, Allen’s only notion of Black people came from warnings to “avoid downtown” and racial slurs sung during schoolyard games. Allen remembered once seeing lines of white mine workers so caked in coal dust that he mistook them for Black people.

“The nearest major town was Bluefield, Virginia — the heart of coal country,” said Allen. “One day, there were dozens of workers, and almost all of them were totally black. All you could see were the whites of their eyes. I remember asking my mother, ‘Are these colored people?’”

It wasn’t until Allen attended Scarritt College — a Methodist college in Nashville, Tennessee — that Allen was exposed to a diverse community, including meeting the 23-year-old John Lewis, who was visiting as a guest speaker. “He spoke very softly and directly, very heartfelt,” said Allen. “This was the first person I had heard speak about the civil rights movement, especially a Black person.” According to Allen, Lewis was arrested the very next week for protesting segregation at the local YMCA. “That was the beginning of my involvement with the movement,” he said.

The tactic Lewis and student organizers chose was to target businesses that refused to serve Black people. During one demonstration at a shopping arcade, several protesters were attacked and arrested, while Allen was knocked to the ground in front of the segregated Tic Toc restaurant.

A white man had emerged from the restaurant, using an epithet common to the South in 1964: “What’s a white boy doing with all those n*****s?” the man shouted, grabbing Allen by the tie and preparing to launch his fist into Allen’s face. Luckily, Allen was wearing a clip-on tie that day.

“When he grabbed it, it came off, and the tie on the floor threw him off,” said Allen. He soon found himself on the ground, knocked over by the aggressive melee surrounding him.

Later that year, Allen was arrested as he led a group of anti-segregation protesters in downtown Nashville. Police blocked their path, and an officer grabbed him by his belt loop. “I went limp, and they threw me in the paddy wagon,” said Allen. “When I told my mother I was arrested, she was in great shock. She said, ‘No member of our family has ever been arrested!’ … Being arrested was a badge of honor, and there were many people in the demonstration who were disappointed that they had not been arrested.”

Despite the intensity of such encounters, Allen said he rarely felt fear. “Bravery had not a lot to do with it. It was the logical next step,” he said. The threats confronting Black members of the movement, Allen emphasized, were always greater. “After the Freedom Rides and the early sit-ins, John Lewis went back to Alabama with Bernard Lafayette, where they were killing people for even thinking about registering [to vote]. That, I consider courageous.”

Today, John Lewis, who died at age 80 in 2020, is remembered for his Herculean actions during the civil rights movement: lunch counter sit-ins, the 1963 March on Washington, the concussions he survived during Freedom Rides and the “Bloody Sunday” march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge. As his traveling companion in the early ’60s, Allen saw a different side of Lewis.

Sign up for Indy Today to receive fresh news from Independent.com, in your inbox, every morning.

“John was always photo-conscious. When he was engaged in demonstrations, he was the epitome of seriousness. You never saw him smile at all,” said Allen. “In relaxed moments, he was a totally different person.” Lewis had a knack for impressions of notable civil rights figures, said Allen — the very same figures who forced him to edit out more radical portions of his speech at the 1963 March on Washington.

“When the Big Six went to the White House, Kennedy was trying to talk them out of marching. A. Philip Randolph — the father of the March on Washington — was a very stately, tall man. And John would mimic him saying, ‘Mr. President, the masses are restless!’ He would do an excellent John Kennedy in response. And he would do Martin Luther King Jr. at the March on Washington — ‘Give us the ballot!’”

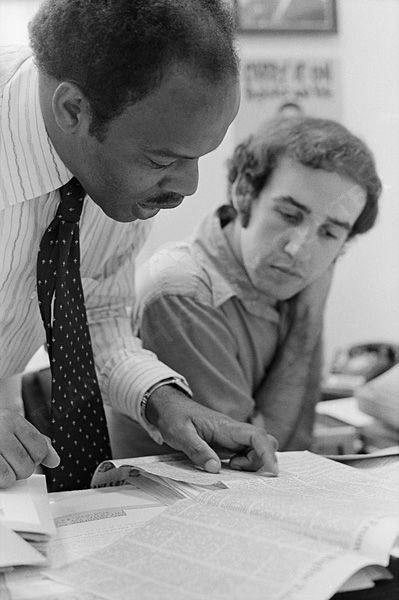

Allen was working in human relations in Nashville when Lewis became the director of the Voter Education Project 1971, which aimed to register minority voters in the South. Lewis hired his friend as communications director, and they launched Voter Mobilization Tours throughout Mississippi, Louisiana, and Florida.

“We were brothers; we were constant companions; we traveled together,” said Allen. “Even when we were not in the office setting, he was probably my closest companion and friend throughout that whole period.”

Lewis went on to run for Congress in 1977, though he was not elected until 1986. Allen served in the human rights movement for 16 years before becoming a doctor of chiropractic and kinesiology in 1985. His practice began in the same Santa Barbara building he works in today, and for 25 years, he’s taught wellness courses at SBCC and the school’s Continuing Education.

Voting Access Now

Fifty-six years after the Voting Rights Act passed, Republicans in state legislatures are passing bills to suppress the vote, and Congressional Democrats cannot deliver their own bills in the Senate — most recently the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, which was blocked by filibuster last Wednesday. The bill would have maintained the federal approval required before states with histories of racial discrimination could alter election laws — or “pre-clearance” — a provision the Supreme Court struck down in 2013. As a result, Texas changed its voting maps this October, and despite four million new residents since the last Census — many of whom are Latino Americans — the state failed to add a single majority-Latino district.

NOW IN S.B.: Archie Allen at his chiropractic offices on Arrellaga Street. Credit: Caleb Rodriguez

“When the Supreme Court struck that provision, they took the heart out of [the Voting Rights Act],” Allen said. “The whole deal was that we were making progress…. So, that was a blatant affront to everything we were working for.” Yet, John Lewis’s legacy remains important in the fight for the right to vote, said Allen.

“When John died, millions of people turned out with heartfelt support,” he said. “Just as we could not have imagined that [our work] would all have to be redone, we could not have imagined the overwhelming support that this movement for justice and equality brought into focus….

“Us old folks are proud of the youngins, who have not only carried it through but have carried it far beyond what we could have imagined at that time,” said Allen. He thought a passage in John Lewis’s 2012 book about the passing of the torch said it best:

“Ours is not the struggle of one day, one week, or one year…. Ours is the struggle of a lifetime, or maybe even many lifetimes, and each one of us in every generation must do our part.”

Support the Santa Barbara Independent through a long-term or a single contribution.

You must be logged in to post a comment.