Poodle | History Is Bunk in the Wake of Recent Supreme Court Rulings

Riffing on Abortion Rights and Concealed Weapons

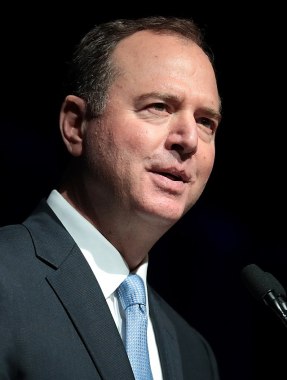

“History is bunk!” Or so said Henry Ford, founder and Grand Poobah of America’s automobile industry many moons ago. “The center held,” stated California Congressmember Adam Schiff just this week during Day Four of the January 6 hearings. “But barely.” And lastly, there’s “I want to believe,” the not-so-subliminal but unstated mantra of Fox Mulder — UFO hunter and conspiracy investigator extraordinaire of X Files fame. For some reason, these three unrelated statements keep colliding around my brain in the wake of the Supreme Court’s two earth-shattering rulings this week.

I’m still trying to figure out why.

Henry Ford’s classic line — which he probably didn’t really say that way — is actually kind of obvious. This week, the Supreme Court voted six to three to give brand-new and expanded rights to gun owners to carry concealed weapons in public. This very same week, the very same six members of the Supreme Court voted to take away abortion rights that had existed in some form in all 50 states for the past 50 years.

Let’s do the legal math: Guns, yes; women, no.

The authors of both opinions — Justice Clarence Thomas wrote the first and Justice Samuel Alito the second — rooted their arguments almost exclusively in their notions of history. Because abortion is not mentioned anywhere in the Constitution and was not “legal” at the time the Constitution was written, Alito argued, the constitutional protections afforded it in 1973’s landmark ruling, Roe v. Wade, no longer pass constitutional muster. As a result, abortion has just been outlawed in 22 states with four more on the way.

Justice Thomas similarly cited the historical record when it came to a 120-year-old New York law that until this week gave law enforcement authorities the legal discretion whether to issue someone a concealed weapons permit or not. In this case, Thomas took issue with the requirement that applicants must demonstrate they had a “good cause” and “special need” to pack heat. Thomas deep-sixed the “good cause” requirement arguing that only if a firearm restriction is consistent with the nation’s “historical tradition” could it be found to conform to the Second Amendment. If not, he ruled, it would be out.

Both Alito and Thomas purported to have examined the historical record where their respective cases were concerned and found that the cupboards were bare.

As someone who got a degree in history, I can say that “the historical record” is inherently, inevitably, necessarily selective and incomplete. First, most history is written by the winners and by liars, often with self-serving axes to grind and pasts to hide. But even when it’s not, history is highly complex and almost always contradictory. People see things differently. Memories fade. It’s a mess. That’s why I love it. That’s also why I think history is too important — and too interesting — to be trusted to historians. But seeing now how it’s been mangled and manipulated by the likes of Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito, I may have to rethink that opinion.

Alito is, of course, correct. There’s nothing in the Constitution about abortion. There’s nothing in it about women either. But you don’t have to look that hard or that long to uncover a rich historical record about how women in colonial times sought to terminate unwanted pregnancies in a host of ways and for a host of reasons. All kinds of potions were available to induce miscarriage, some safer than not. Childbirth was medically risky. Then, as now, women got pregnant out of holy matrimony, but back then, that was a major scandal.

In the 1850s, medical care started to assert itself as more of a codified profession with standards of conduct, dominated — naturally — by men. To the extent women health care providers had been involved, they needed to be pushed to the dustbin of history. To the extent laws started creeping on to the books that criminalized abortion, it was because the practice had claimed the lives of mothers, not the fetuses. Not coincidentally, such laws also helped eliminate midwives and their ilk from the competitive picture.

At least that’s one school of historical thought. It’s not one that Samuel Alito ever saw fit to acknowledge, let alone explore.

Who Alito did see fit to mention in his demolition of Roe v. Wade, several times in fact, is even more chilling. Several times, Alito cited a 17th-century jurist named Sir Matthew Hale to demonstrate how British common law was similarly silent on the subject of abortion rights. In his time, Hale was revered and esteemed and all the other words of approbation that befitted a Lord Chief Justice, which is what he became in 1671. Hale, Alito noted, described abortion as a criminal act, even in some circumstances a homicide. Today Hale is perhaps most famous — infamous might be the better word — for establishing the legal doctrine that it was impossible for a husband to rape his wife. Wives gave up all rights to give consent, Hale concluded, when they entered into the contract of matrimony. And this legal holding would continue to hold sway in American courts until about 25 years ago.

Sign Up to get Nick Welsh’s award-winning column, The Angry Poodle delivered straight to your inbox on Saturday mornings.

Anyone wonder why the Equal Rights Amendment never got ratified?

Hale also helped establish the judicial tradition of doubt and skepticism where and when the testimony of rape victims was concerned. Did they resist loudly and forcefully enough, he always wanted to know, to say they’d actually been raped? And the answer was rarely affirmative. His concern for the reputation of the accused in such matters was always paramount.

painting by John Michael Wright 16617-1694

Guildhall Art Gallery, London | Credit: Courtesy

Lastly, before Hale retired, he would also order the execution of three women who’d been charged of witchcraft. This came at a time when witchcraft trials were already being seen as outdated, outmoded, and perhaps even a little barbaric. Yet he persisted. According to some schools of historic thought, Hale’s legal spadework was heavily relied upon in 1692 during the witch trials for which the witch trials of Salem would become famous.

At the risk of repeating myself, the historical lens is inevitably selective and subjective. In this case, it makes me wonder more about the person holding the camera.

Justice Clarence Thomas is similarly arbitrary and capricious when strip-mining the historical record in support of his legal argument that the Creator endowed all of us with an inalienable right to wear concealed weapons as a necessary fashion accessory. Because there weren’t laws on the books requiring a “good cause” finding back in 1891 or 1868, Thomas decreed, the law adopted by the New York State Legislature way back in 1905 that actually does so is now fatally flawed from a constitutional perspective. Given that California passed similar legislation, we will be immediately affected. Thomas does, however, admit that Texas — back when it was still a territory — had adopted a good cause requirement. A couple of other places did too. But these, Thomas chooses to shrug off as mere “outliers.”

Selective? Subjective?

Last week, Adam Schiff breathed a most apprehensive sigh of relief during the January 6 hearings, extolling the unsung heroics of various elected officials up and down the food chain that stopped former President Trump from stealing the 2020 election. “The system held,” exclaimed and exhaled Schiff.

“Just barely.”

Naturally — like Fox Mulder — I want to believe.

But like Chief Justice John Roberts, I have my doubts.

Roberts, for the record, voted to repeal Roe v. Wade. But he cast a dissenting concurrence in which he all but coughed up big hairy fur balls at what he described as the gratuitous overreach of the court’s new conservative majority. Roberts — who finds himself now a Chief Justice of One — castigated his colleagues for what he called “a relentless freedom from doubt.” He pointedly pointed out they could have easily upheld a Mississippi bill that would have all but obliterated a woman’s right to choose without upending 50 years of jurisprudent precedence. Roberts is troubled by a keen awareness that the court is supposed to play the role of “the middle.” At a time in history when there is a conspicuous dearth of middle ground, the majority’s decision to burn down the whole house struck Roberts as inflammatory and incendiary. “If it is not necessary to decide more to dispose of a case,” he wrote, “then it is necessary not to decide more.”

While Roberts discovered he was talking only to himself, Justice Alito took pains to insist he was writing only about Roe v. Wade — and its legal underpinnings. Nothing in his opinion, he repeatedly stressed, should be construed as an attack on such established rights as gay marriage, gay sexual relations, and even access birth control. All of these rights are rooted in exactly the same legal framework as Roe v. Wade — the right to privacy and the pursuit of happiness as defined, both implicitly and explicitly, in the 14th Amendment. But if Roe v. Wade is legally bankrupt because this is shaky constitutional ground, then so too are those “rights.”

Naturally, I want to believe Alito when he says these legal questions are totally separate. The problem, however, is Clarence Thomas. In his concurring opinion, Thomas explicitly calls out these three rights, saying they rest on “demonstrably erroneous decisions” and that they all need to be revisited.

To be clear, Thomas believes we need to reexamine a case decided by the Supreme Court back in 1965 that concluded a married Connecticut couple could purchase contraceptives legally. On the books at that time was an 1879 law that barred the use of contraceptives of any kind. This ruling inferred the existence of a “right to Privacy” in the 14th Amendment, which bestows on all citizens the right to life, liberty, or property without due process.

We can all believe all we want, but the Supremes have beggared our collective credulity. Senators Susan Collins (a liberal Republican) and Joe Manchin III (a very conservative Democrat) both called out Supreme Court Justices Brett Kavanaugh and Neil Gorsuch, all but accusing the two of lying to them about their inclination to rely on established law. In a private meeting with Collins, before his confirmation, Kavanaugh sought to reassure the Maine Senator that he believed in precedent. “Roe is 45 years old. It has been reaffirmed many times, lots of people care about it a great deal, and I’ve tried to demonstrate I understand real-world consequences,” he said. “I am a don’t-rock-the-boat kind of judge. I believe in stability and in the Team of Nine.” Based on this reassurance, Collins voted to confirm Kavanaugh.

The boat’s been pretty well rocked. Capsized, more like it. And we all got drenched. And as for Adam Schiff’s allusion to the middle holding, well, it comes from an Irish poem by William Butler Yeats called “The Second Coming.” As a rule, I avoid both poets and poetry. But in this case, I’ll make an exception. “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold,” Yeats wrote, later adding, “the best lack all conviction, while the worst / are full of passionate intensity.”

Guns, yes; women, no.

History ain’t bunk. That is.

Support the Santa Barbara Independent through a long-term or a single contribution.

You must be logged in to post a comment.