Santa Barbara Wine Saved My Life

How This Former Hospice Chaplain and Author of 'Blood from a Stone' Found Redemption

I used to walk up the hill to visit the Queen of the Missions on late Sunday afternoons. I would perch on her steps as the sun fell into the sea, her twin bell-towers sheltering me from the breezes rustling down Mission Canyon. I would let my gaze be swept out beyond the lawn and roses to the Spanish tiles glowing in the waning light, and finally to the rippling slate blue of the Santa Barbara Channel and the peaks of Santa Cruz Island.

Sometimes, from my viewpoint, I would think about the Santa Cruz Island Wine Company, which boasted the largest winery and vineyard in the area at the turn of the 20th century. It was said at the time that “the most romantic vineyard is out at sea.” That operation is long gone, but a few years ago, the Rusack Winery took cuttings of the few remaining Santa Cruz zinfandel and mission grape vines, still clambering up trees 100 years later on the back side of the island, and planted them in Ballard Canyon near Los Olivos. The past is not dead as long as there are dusty bottles and old vines.

I may have moved here to join the wine industry, but it didn’t take long until I found the history of Santa Barbara to be just as intoxicating as its wine. Spanish sea captain Sebastián Vizcaíno gave the modern name to the area when, tossed in violent seas in our Channel on his voyage up the California coast, he cried out to Santa Barbara for rescue on the eve of the saint’s feast day. That was December 4, 1602.

Almost two centuries later, what would come to be called the Queen of the Missions was baptized on December 4, 1786, set in an amphitheater of hills above her burgeoning pueblo. Sailors would use her as a beacon for steering safely into port. Santa Barbara has been saving people ever since.

Before I relocated here nine years ago, I lived about 30 miles east of Los Angeles and worked as a hospice chaplain and grief counselor. I would drive to homes and facilities all throughout the San Gabriel Valley and East L.A., to sit with people who had been given a terminal diagnosis and with their families who were watching their loved ones die.

Sometimes I would be holding a patient’s hand when she took her last breath. I worked many shifts in the middle of the night on what we called “death visits.” I would get called to be with a family after a patient had died, to help handle the mortuary arrangements, to hear the stories the family was desperate to tell about the person they had just lost, and to be a comforting presence for the few minutes we had together.

When I told people what I did for a living, they would often respond, “Oh, that takes such a special person.” I knew I wasn’t that special. It was sacred, necessary, strange, deeply meaningful work. But it was also a slow leak on my soul, and my capacity for joy and celebration was slowly, but inexorably, deflating. Sometimes I worried my patients weren’t the only ones who were dying.

During those hospice years, it was the Santa Ynez Valley that became my refuge. I would blast right by Santa Barbara on my way over the mountains to the vines stitched along the hillsides. Often I would go round-trip in one day, sometimes when my hospice shift began at midnight that night, just to smell the air crackling with the vapors of pinot noir and to partake for a few hours in a world that felt so astonishingly alive. I fantasized about giving it all up, disappearing into wine country, and fading into myth. But I never thought I would actually do it.

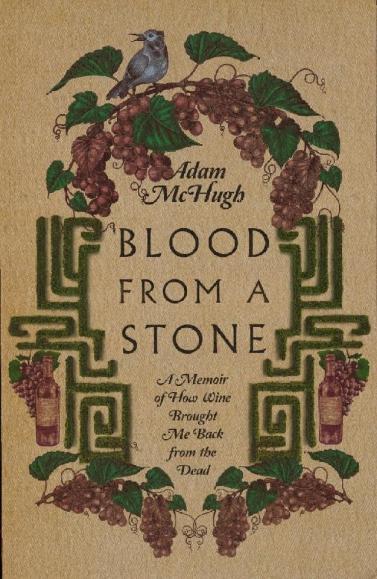

My book Blood from a Stone: A Memoir of How Wine Brought Me Back from the Dead was published in October, and it tells the story of how my hospice career ended and how my life in L.A. unglamorously fell apart. And it tells the story of how I moved to Santa Barbara, where my work and participation in the tight-knit wine community downtown helped me to heal and begin to put a new life together. My Sunday evening meditations at the Mission helped.

Santa Barbara has always been a healing place. In the 1870s, after the golden spike was driven into the transcontinental railroad, doctors back east began prescribing the climate of Santa Barbara to their convalescent patients. The salty sea air combined with the south-facing beaches that lounged under the long arc of the sun was considered medicine for the sick.

Or you could take the short journey into the foothills of the Santa Ynez Mountains and recuperate in natural hot springs. So wealthy patients took the train to San Francisco and boarded a steamer to Santa Barbara, where they checked into the Arlington Hotel and stayed for weeks or months. Santa Barbara boomed as a high-class health resort, earning itself the nickname “The Sanitorium of the Pacific.”

Down the beach a few clicks, the little village of Summerland was founded in the 1880s as a Spiritualist colony, by a group of people who were intent on communicating with the spirits of the deceased, which, let’s be honest, is weird. But it does seem there is a long history of Santa Barbara calling people back from the dead. And I am grateful to be one of them.

Eventually, the call of the vines of Santa Ynez became irresistible for me, and I made the climb over the mountains. But Santa Barbara is still my healing place.

Adam McHugh’s new book is Blood from a Stone: A Memoir of How Wine Brought Me Back from the Dead. Follow him on Instagram at @adammchughwine.

Support the Santa Barbara Independent through a long-term or a single contribution.

You must be logged in to post a comment.