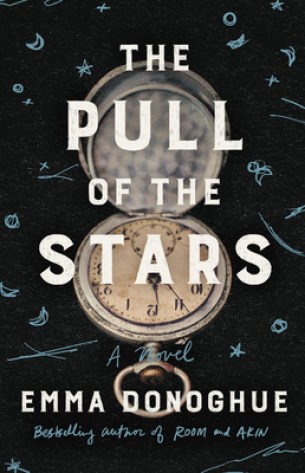

Review | ‘The Pull of the Stars’ by Emma Donoghue

A Prescient Novel of a WWI-Era Pandemic

“In October 2018, inspired by the centenary of the great flu,” Emma Donoghue tells us in the Author’s Note of her new novel, “I began writing The Pull of the Stars. Just after I delivered my last draft to my publishers, in March 2020, COVID-19 changed everything.”

Indeed, it did, and how prescient Donoghue’s novel seems now, with its descriptions of a pandemic that has swept through Dublin during the First World War. Businesses are boarded up, hearses line the streets, and those who have yet to be infected shrink away from those who may be. It would be a uniformly grim picture if not for the two protagonists. Julia Power, who has already had her “dose” and “come through practically unscathed,” is a soon-to-be 30-year-old nurse working in an improvised maternity ward for quarantined mothers. She is unflappable, although “the great flu, khaki flu, blue flu, black flu, the grippe, or the grip” seeps into every corner of the hospital where she works. On the day the novel begins, she is given a new volunteer helper, Bridie Sweeney. Bridie is young, poor, and uneducated, but she is energetic and as imperturbable as her mentor.

Nurses, as they continue to do today, keep the hospital running, while the male doctors are conceited and if not exactly stupid, then hardly the peers of the women who work for them. One doctor is an exception, though she is a woman. Like the real Dr. Kathleen Lynn, who had briefly been jailed for supporting Irish independence, Donoghue’s character is smart, tough, funny, and willing to listen to the nurses who know her patients better than she does.

While the novel makes brief detours to the gray streets of Dublin, to Julia’s home, where she lives with her shell-shocked brother, and to other parts of the hospital, most of the action is set in the maternity ward, which is actually three beds shoved into a supply room. And yet so much happens in this small room: birth and death, friendship and fear, jealousy and kindness. There are even periodic moments of peace, but underneath it all is the unmistakable specter of the poverty of the young mothers who are the “underfed daughter[s] of underfed generations,” women who are always “on their feet … living off the scraps left on plates and gallons of weak black tea.”

The novel’s title comes from the ancient belief that epidemics were caused by the influence of the stars. And the four sections of The Pull of the Stars — Red, Brown, Blue, and Black — represent the colors of the face in an influenza patient. As Julia explains, “it starts with a light red you might mistake for a healthy flush. If the patient gets worse, her cheeks go rather mahogany.” Later, “Cheeks and ears and even fingertips can become quite blue as the patient’s starved of air.” Finally, Julia tells Bridie, “I’ve seen it darken to violet, purple, until they’re quite black in the face.”

“It’s a secret code,” Bridie says, and, if not quite secret, the code is a key to the novel, which often moves from hope to despair. However, these big themes emerge from close attention to detail. The great triumph of The Pull of the Stars is Donoghue’s careful description of the minute-to-minute life of a nurse fighting to save the lives of her patients. It’s gruesome going at times, but the action is never less than gripping. Moreover, despite the fact that book was composed before our own version of the plague, The Pull of the Stars is certain to be a book that future readers will consult to better understand what happened a little more than one hundred years later in that next great pandemic.

This review originally appeared in the California Review of Books.

Support the Santa Barbara Independent through a long-term or a single contribution.

You must be logged in to post a comment.