No Farms to Condos, Says Goleta

City Files Housing Element, Confronts County on Potential Rezone of Ag Lands

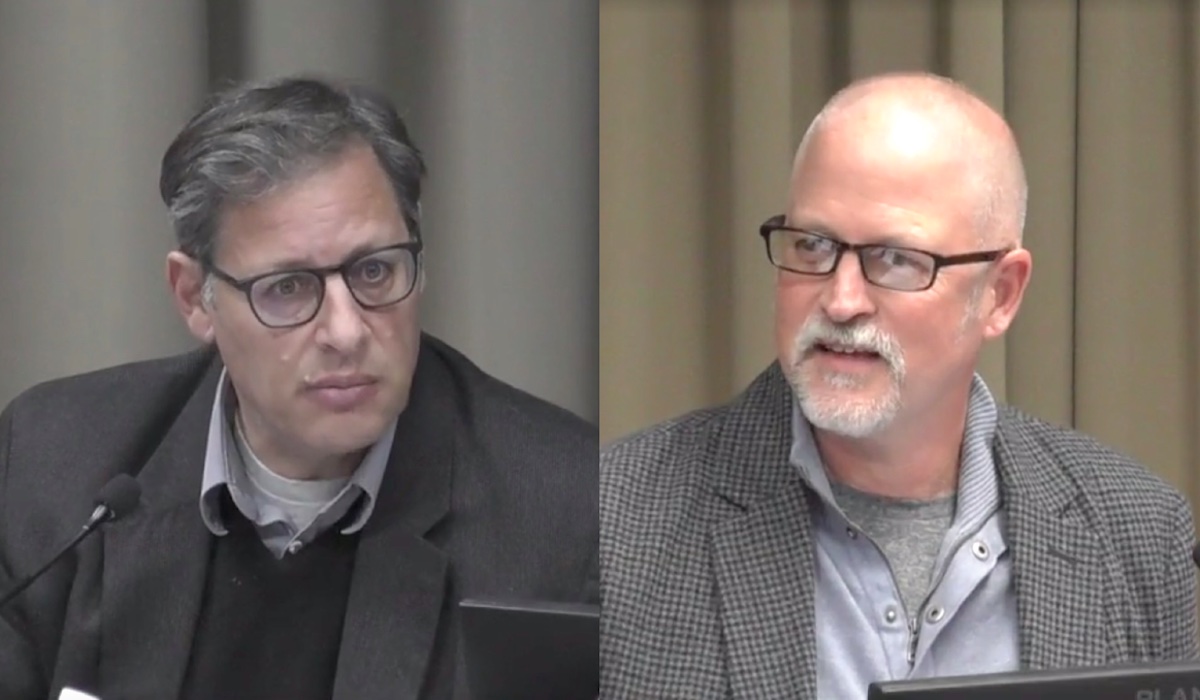

“As a farmer, the best thing you can raise is condos,” said Stuart Kasdin, riffing on the truism about the value of land in the Golden State. Kasdin is a councilmember for the City of Goleta, which just sent its revised Housing Element report to the state, well ahead of the February 15 deadline. But as a small city on the coast surrounded by the County of Santa Barbara, it’s waging another battle to save nearby agricultural lands and open spaces.

Housing element documents are how cities and counties let the State of California know they intend to comply with the laws to zone for more housing and how they’ll do it. To get there, Goleta looked at all its existing zoning within the city and based its Housing Element on parcels that were already zoned for additional housing, infill parcels, commercial areas that could hold mixed-use projects, and everywhere that could have accessory dwelling units (granny flats), said Councilmember Kyle Richards.

But at the county’s first housing element workshop last November, Goleta officials were alarmed to see Glen Annie Golf Club and agricultural areas between Patterson Avenue and Ward Drive marked for development. All are immediately adjacent to the city but under county jurisdiction. Goleta put its concerns into a letter on January 13, over “the apparent lack of transparency and public outreach” in selecting agricultural and open space for rezoning, and asked for the method the county used to conclude that the existing zoning could not accommodate the state housing allocation.

Richards pointed out that the parcels of concern were “landlocked” — “You’d have to go through Goleta to access them,” he said, and impacts were inevitable. “To be fair,” he added, “[the county has] a lot more ag than we have.”

The golf course has expressed its interest in housing since 2009, said Kasdin. In fact, under an earlier, pro-growth City Council, Goleta had applied to the Local Area Formation Commission (LAFCO) to add Glen Annie and the Patterson farm fields to its sphere of influence. “At the time, LAFCO said no,” Kasdin said, outlining that LAFCO was opposed to sprawl and the conversion of agriculture to housing. “The county is now proposing the same thing they objected to then,” he said.

Sign up for Indy Today to receive fresh news from Independent.com, in your inbox, every morning.

The county assigned 1,500 units of housing for Glen Annie, and 2,600 to the ag parcels. Though Glen Annie’s 95 acres are above two schools and El Encanto Heights, both councilmembers thought the backups on Highway 101 a long block away were a significant negative.

“The Storke/Glen Annie intersection at Hollister is already the most congested in the city,” Kasdin said. “At rush hour, the highway traffic is backed up from the Glen Annie offramp all the way to Los Carneros,” which is widely recognized to be a dangerous condition. “Glen Annie is just a little, narrow road,” he added, “and 1,500 housing units there in a city with 11,000 total homes would be 10-15 percent more in just this small area.”

Kasdin also took issue with the county’s assertion that land in Montecito and Hope Ranch was expensive, and that creating affordable housing there would be too hard. “For example, the state has not said, ‘You, Beverly Hills and Santa Monica, you are excluded.’ In terms of environmental justice, it’s absurd that [Montecito and Hope Ranch] would unilaterally not be included.” The state housing mandate was not just for affordable homes, Kasdin added, and includes above-moderate-income homes.

The county supervisors, naturally, had a different take on parcels in the wealthy suburbs. Gregg Hart, now an assemblymember, represented Hope Ranch on the County Board of Supervisors most recently. He said the county would have a credibility problem if it tried to persuade the state that a $5 million estate home was likely to be torn down in favor of a four-story apartment building. “The Housing and Community Development folks are looking for realistic properties that would actually be buildable,” Hart said.

Supervisor Das Williams, whose district includes Montecito, had a similar view on what the state would accept, but also said that the unincorporated county had few commercial sites to consider for a mixed-use designation. However, Williams said he thought the Upper Village on San Ysidro Road was a commercial area with possibilities as it was “close to services and Montecito Union School.”

Although County Planning Director Lisa Plowman indicated her staff were “crazy busy” finalizing the first draft of their Housing Element, Supervisor Laura Capps, who now holds Hart’s seat, had some collaborative words for Goleta: “We share their concerns,” she said, adding that County Planning was talking with the owners of the Magnolia Shopping Center — a spot on Kasdin’s short list of possible alternatives to zoning agricultural lands for development. “I’m happy to say that Magnolia is now on the list,” Capps said.

The wolf at the door, of course, is water. The water purveyor for much of the areas under discussion is the Goleta Water District, which has a water moratorium in place. According to David Matson, assistant general manager for the district, only existing customers may receive water and only up to their historic usage amount. But, with the positive rainfall so far this year, it’s likely the groundwater basin buffer will be met by the fall, which would allow the district to make one percent — or up to 150 acre-feet — available to new customers.

Support the Santa Barbara Independent through a long-term or a single contribution.

You must be logged in to post a comment.