Art from Under the Psychic Hood

Surrealism and Other Left-of-Center Art Featured in Santa Barbara Museum of Art Show ‘Iconography of Dread’

Presently on the savory menu of exhibitions at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, there lurks art of variously subversive ways and means. Wild, abstract-leaning, and rough film-noir-ish impressions are made in the main exhibition arenas where Joan Tanner and Ed and Nancy Kienholz hold forth.

Meanwhile, tucked into the museum’s corner spaces is a deceptively also-ran show called from the museum collection, gamely named Iconography of Dread: Symbolism to Surrealism. In a sense, this small meal of surrealist and symbolist work is the tamer event of the three exhibitions cited here. But it serves the valuable functions of provoking thought, wending down psychological rabbit holes of art history and reminding us of the riches — even of the bizarre, genre-elusive sort — contained in SBMA’s vaults.

Exhibit A, validating all three counts, is the celebrity in the house — Salvador Dalí’s irrational riddle of a painting, “Honey Is Sweeter than Blood.” Long-standing museumgoers will have caught sight of the canvas on many occasions, but it feels especially at home in this surely themed grouping. Painted in 1941, it’s a startling view, with his looming nude female figure (with a crutch) and a Minotaur in retreat conspiring toward a slightly feverish, libido-tinged dream scene in the clouds. Literally.

Fresher visual enticement comes courtesy of the New York School Surrealist Dorothea Tanning, whose 1942 painting “Self Portrait at Age 30” engages the eye and the mind’s eye with its vision of the artist, chest bared and with tree roots growing from her skirt. In this dream-fueled interior, with endless doors, a startled griffin beast casually perches, pet-like, at her feet.

Nearby, in Kay Sage’s 1943 painting “Second Song,” Dalí-esque forms and dislodged logic continue, along with influence of Yves Tanguy, with sensuous, abstracted forms on an imaginary landscape. References to anatomy, architecture, and antiquity are organized with a slyly neat compositional orderliness.

Significant French Symbolist artist Odilon Redon’s “Salome,” dreamed up in 1910 around the time Oscar Wilde and Richard Strauss were reinventing the myth, called on a light, gauzy palette for the archetypally grisly subject of John the Baptist’s head on a platter.

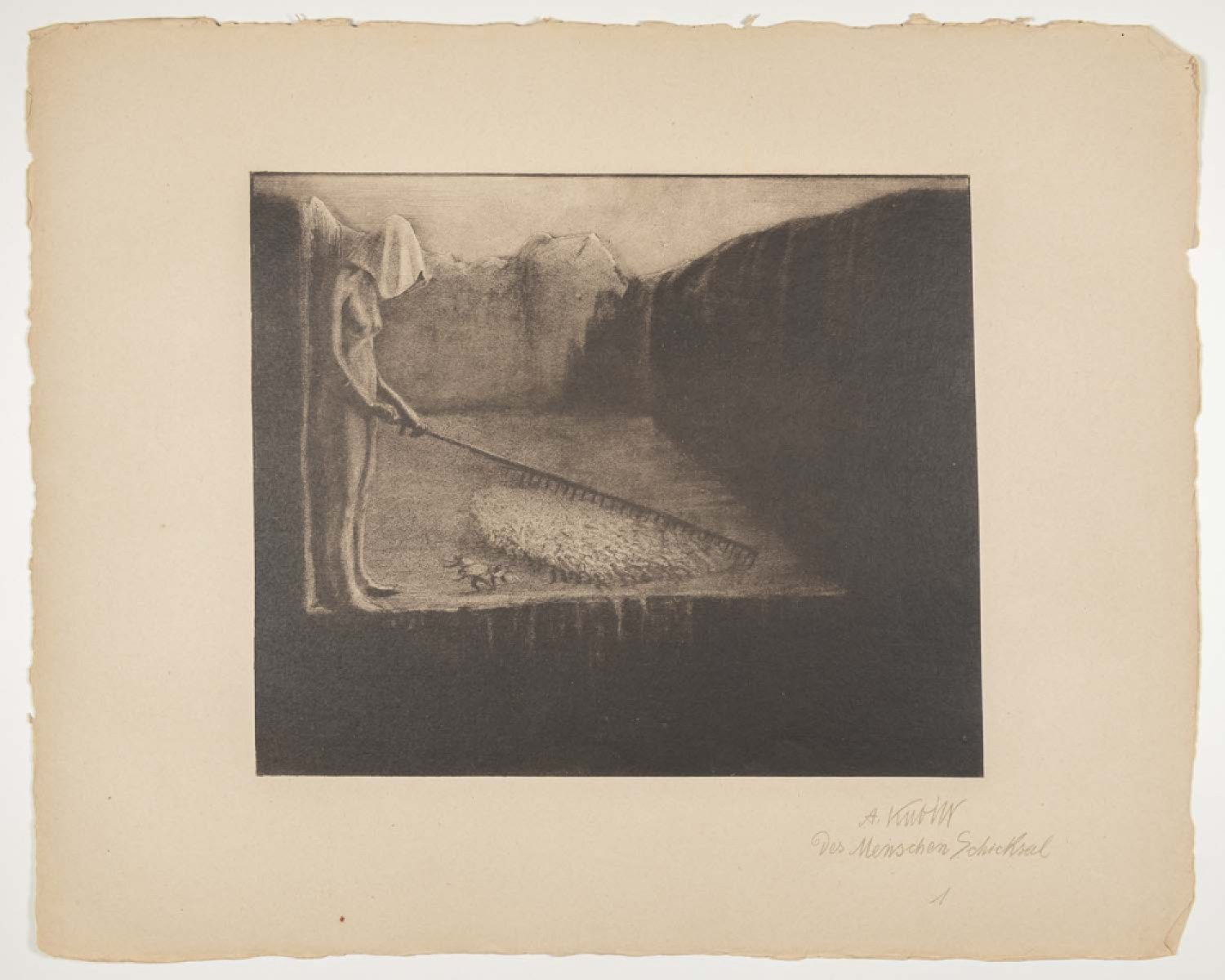

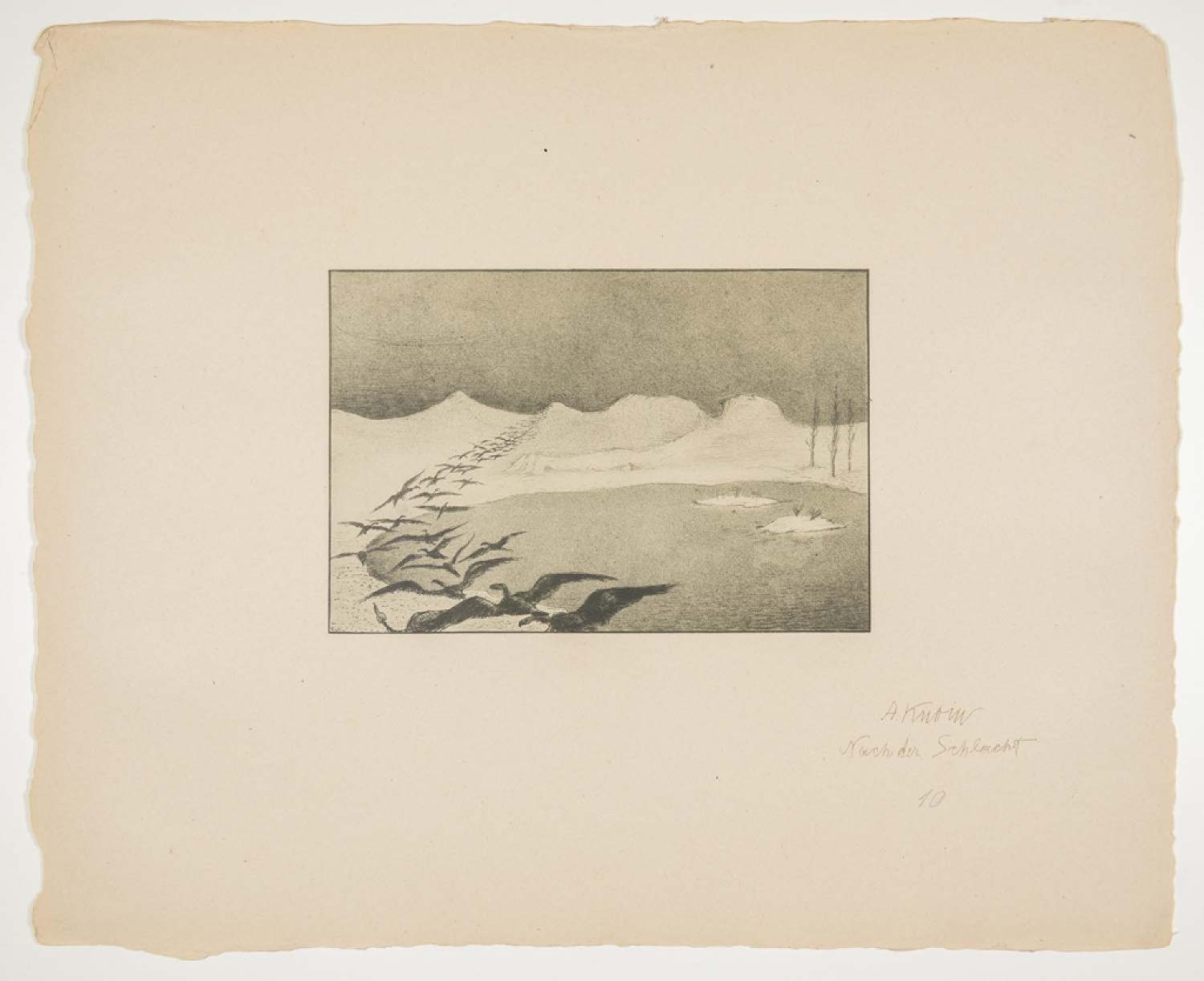

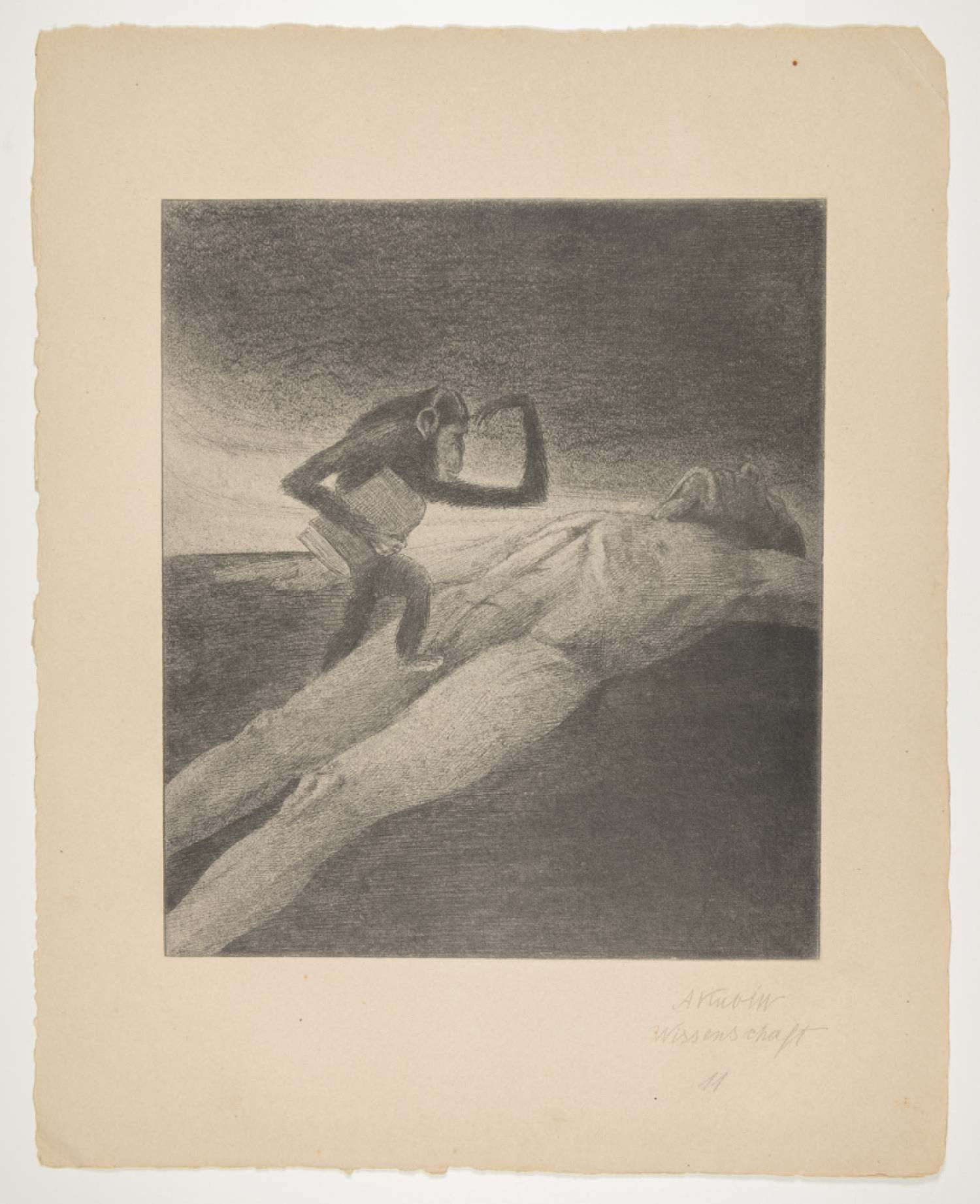

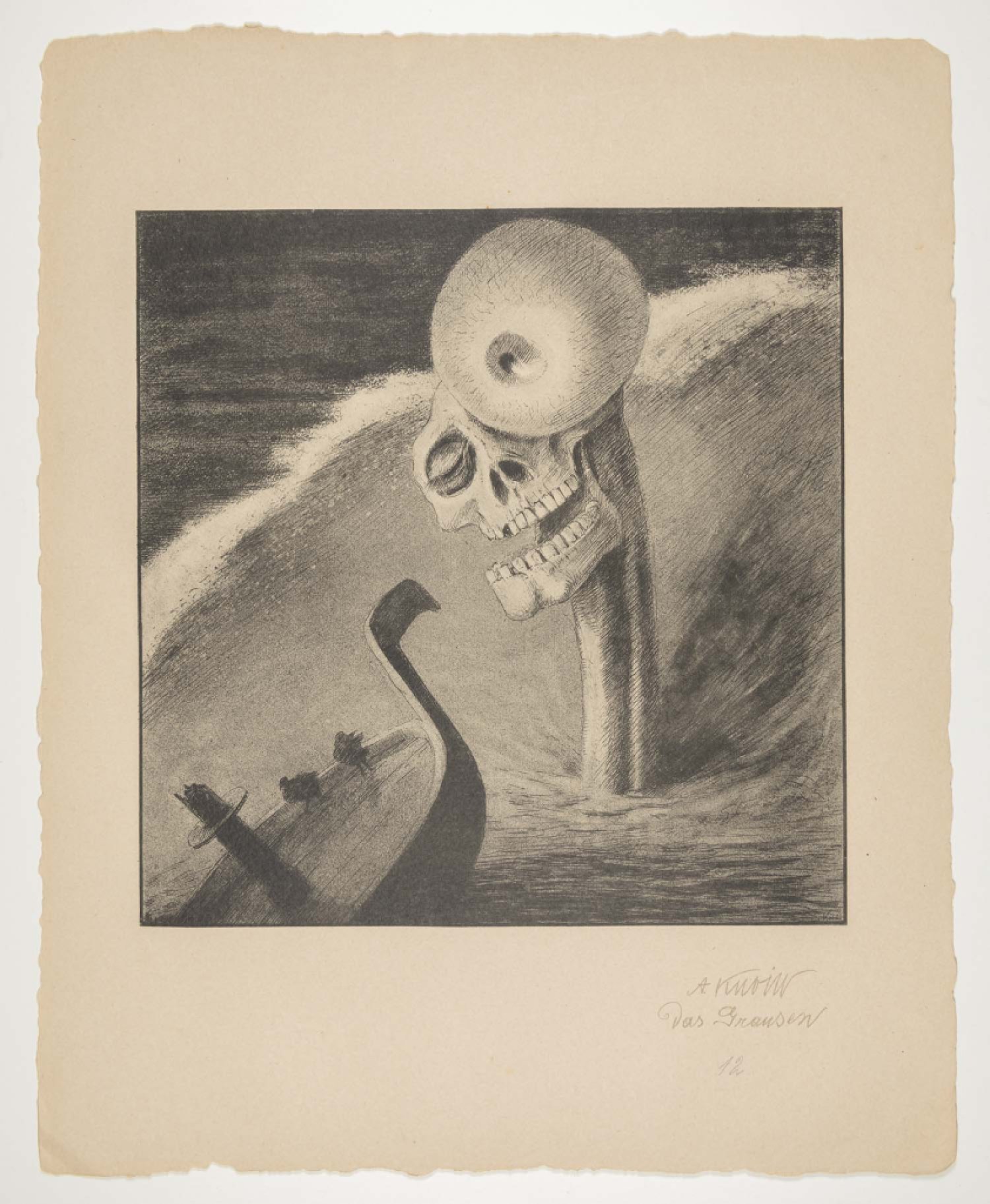

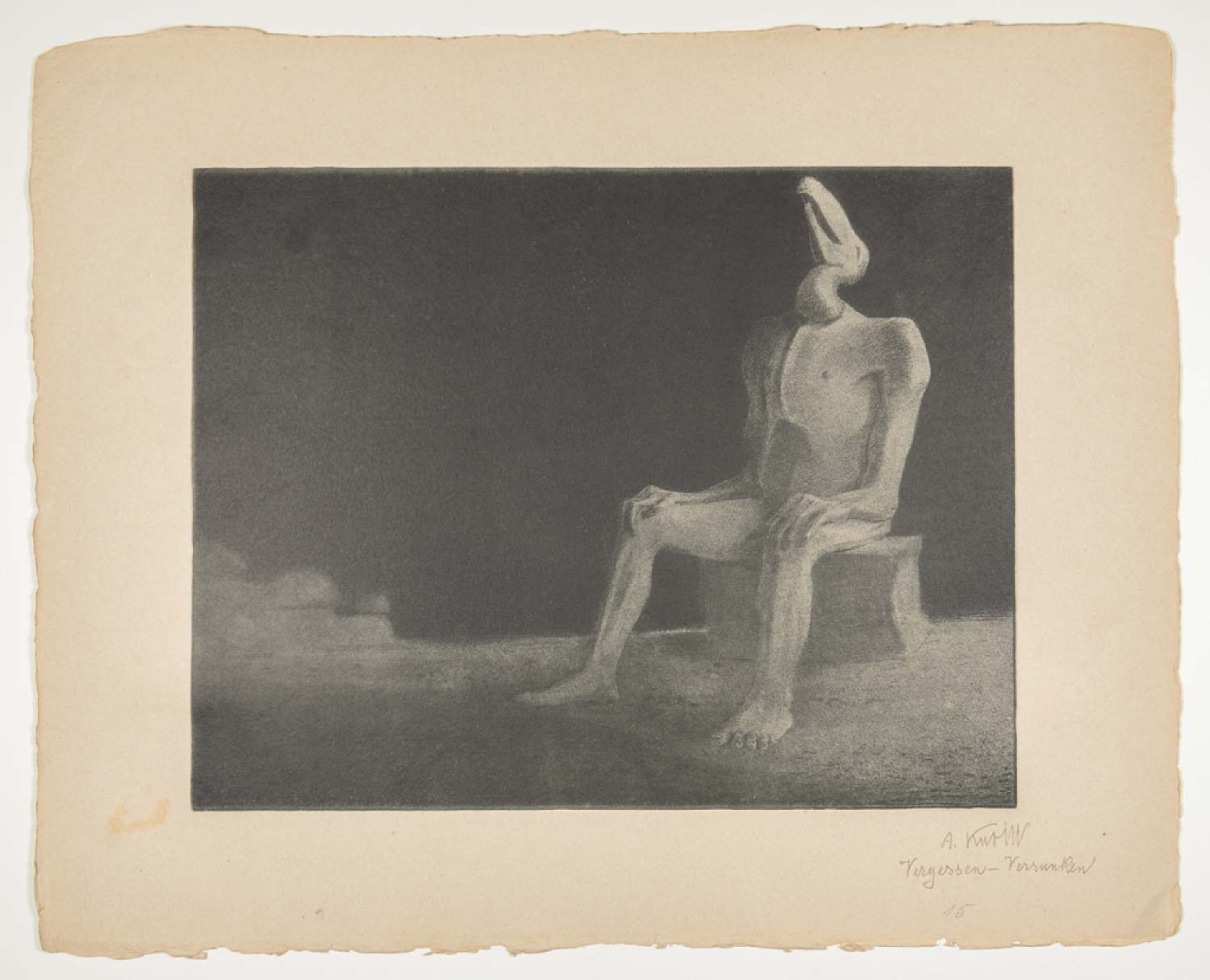

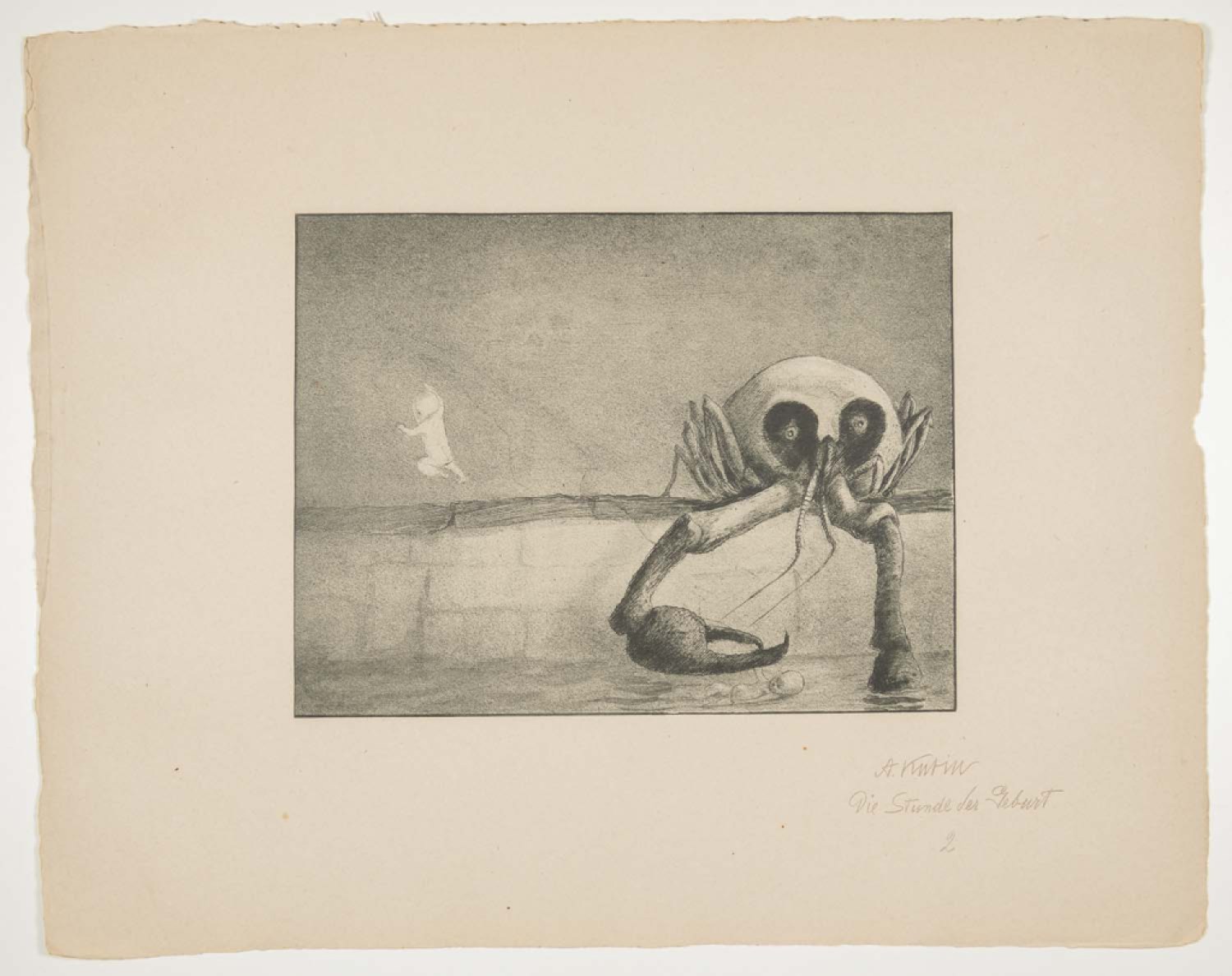

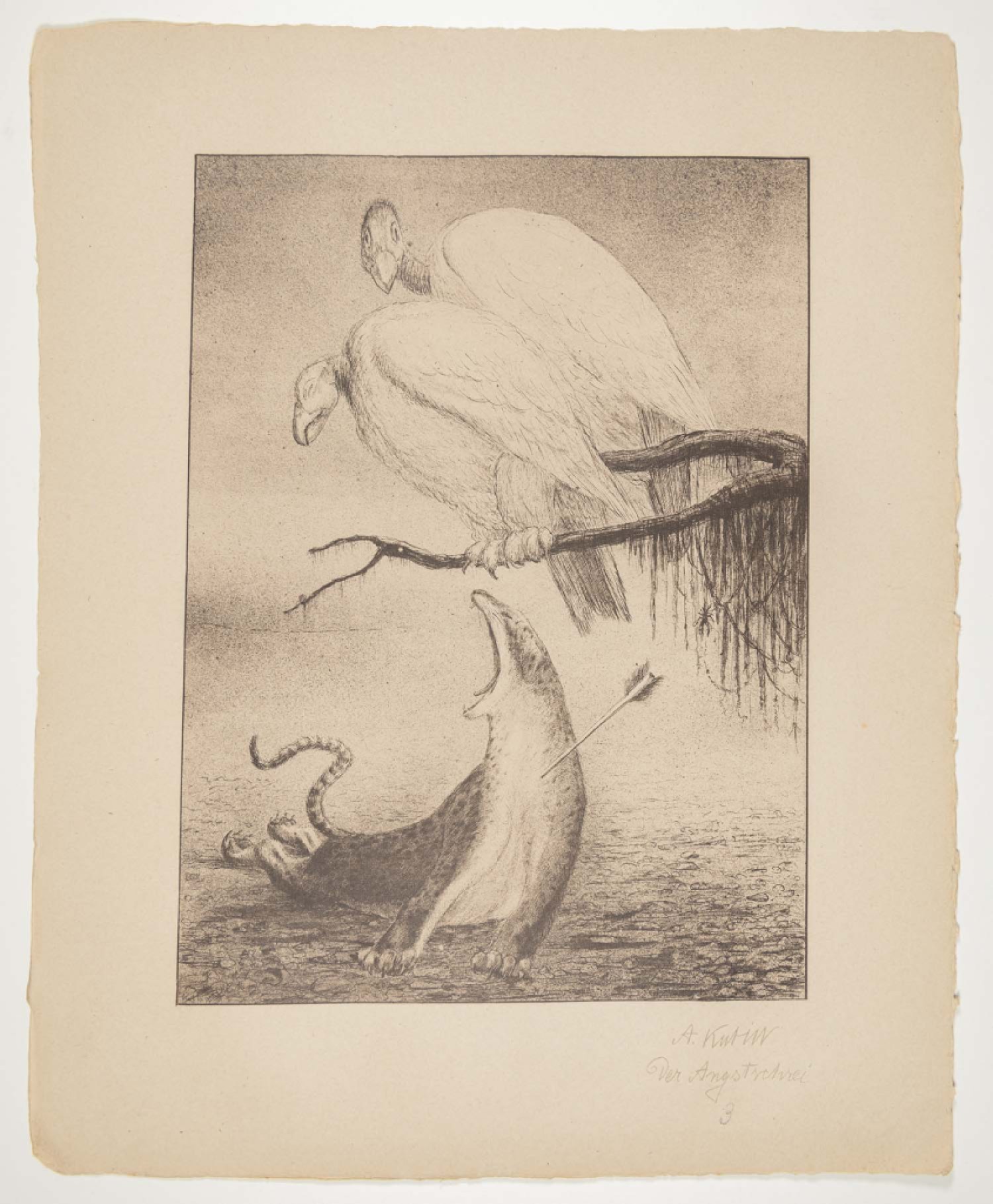

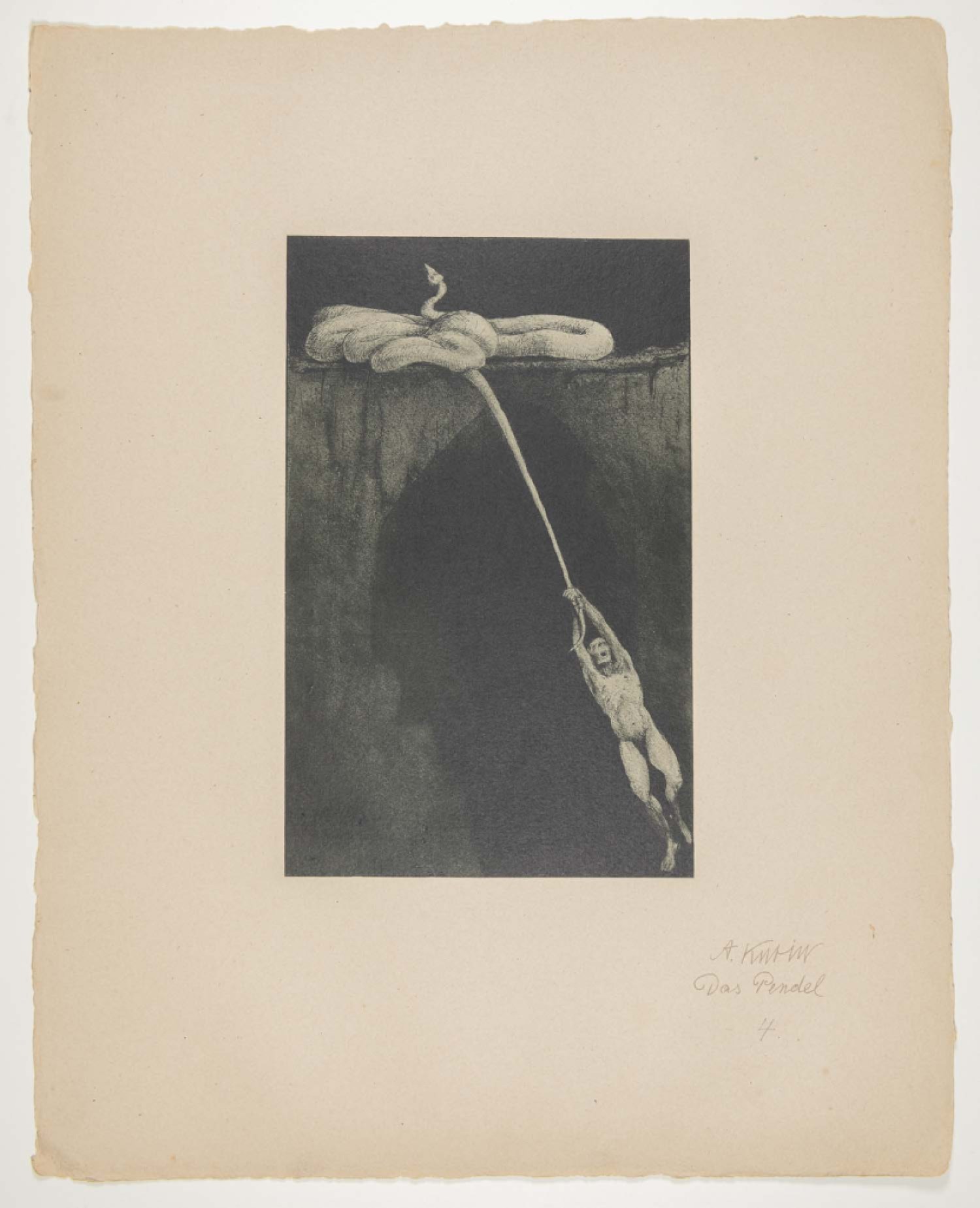

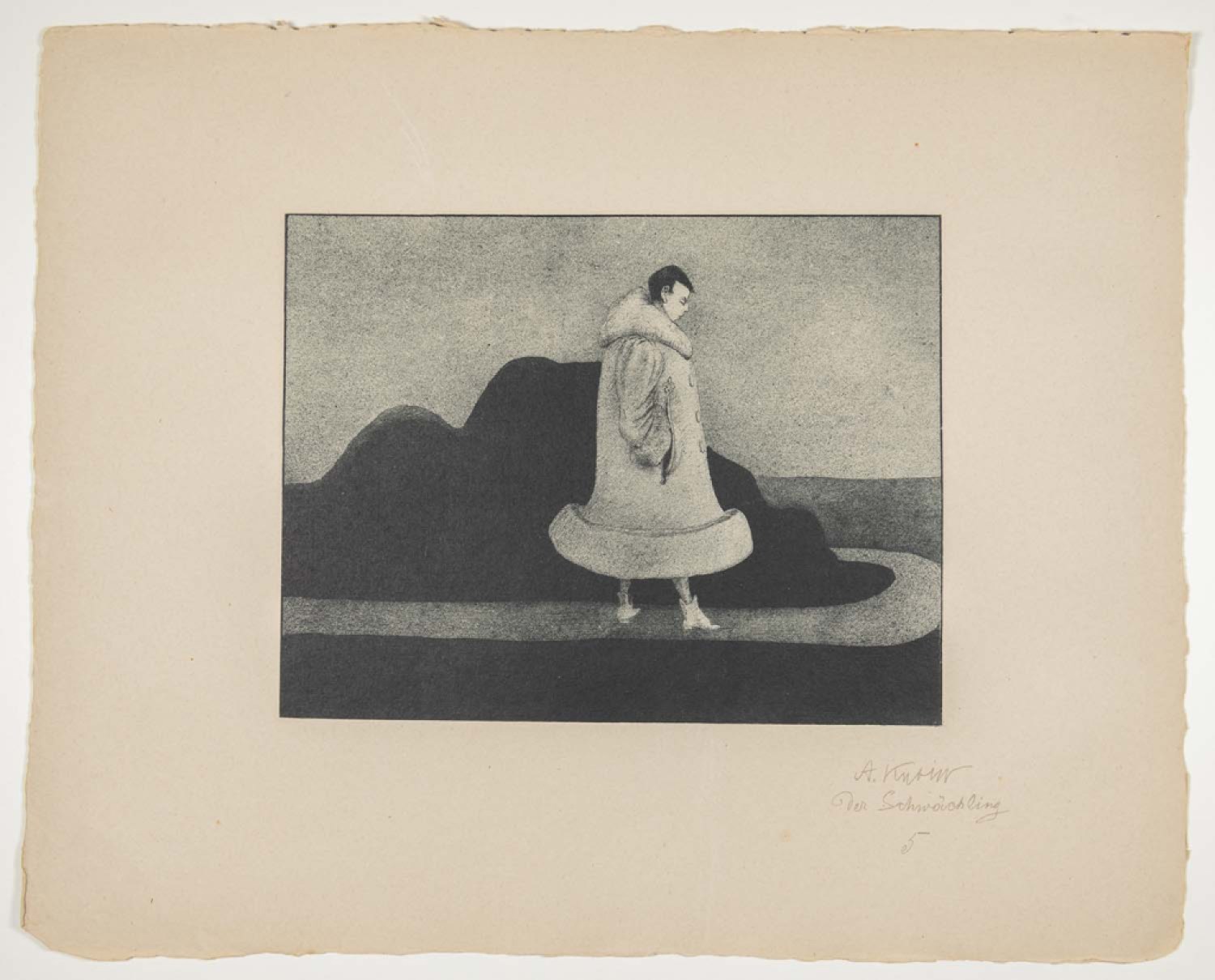

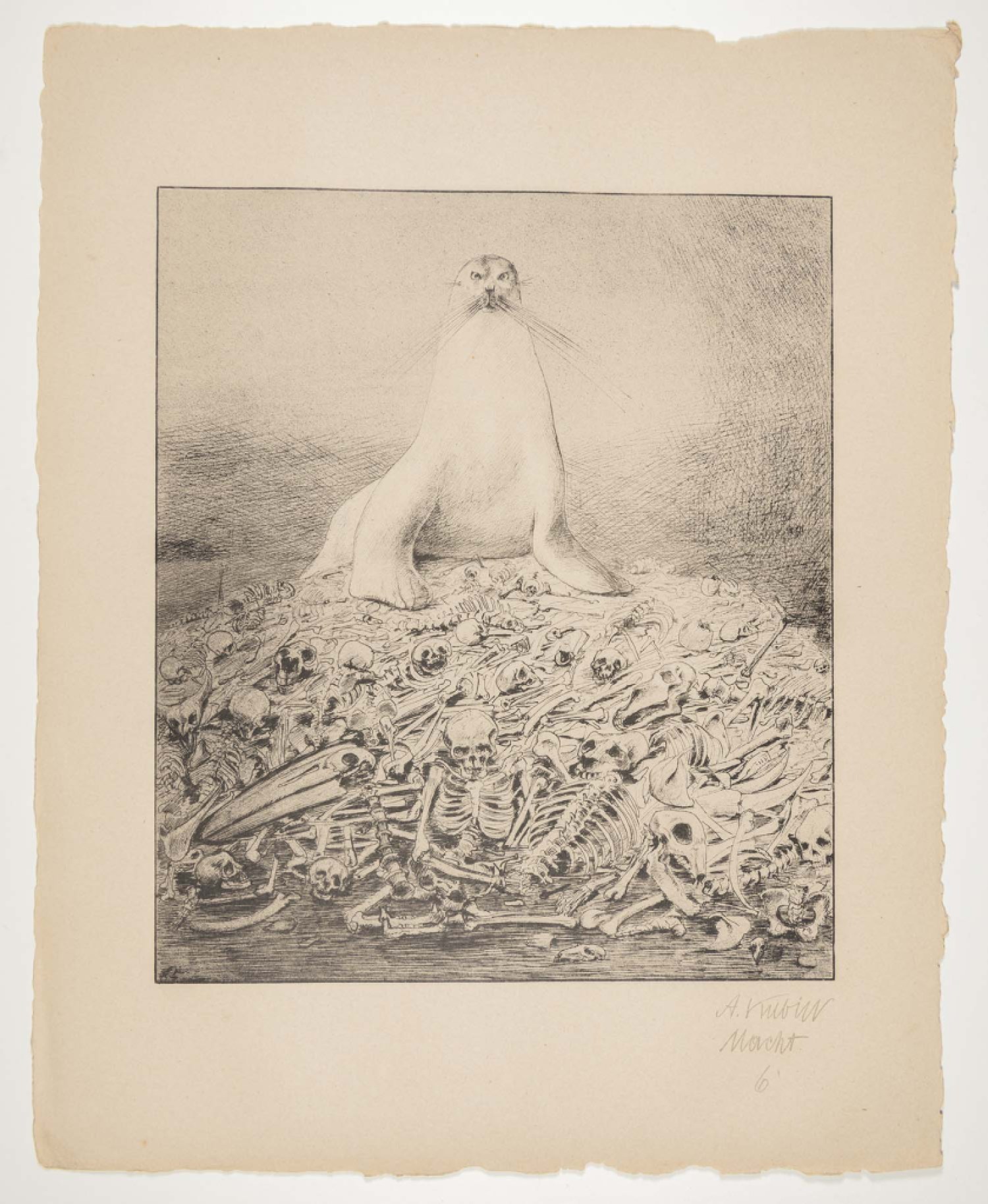

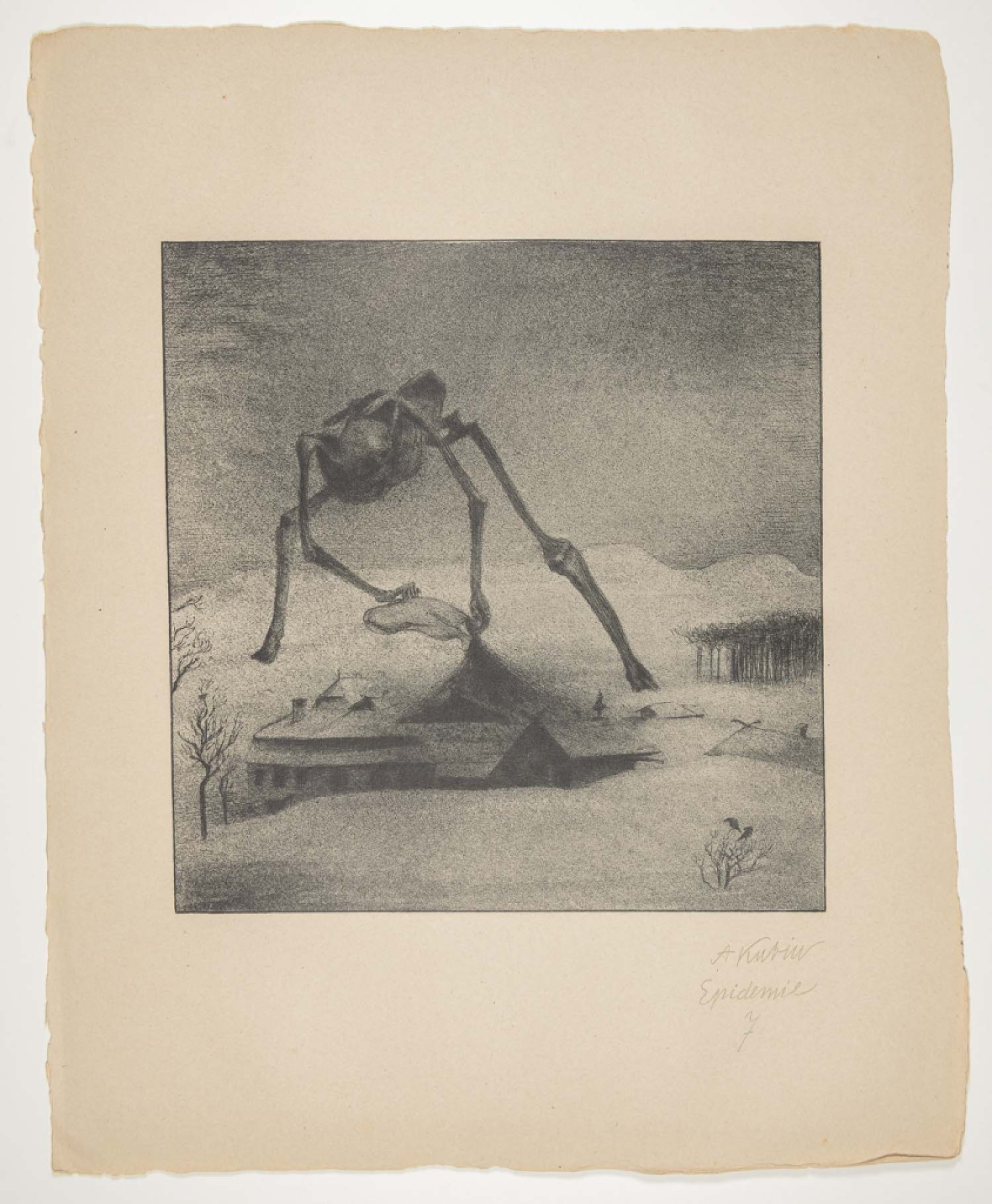

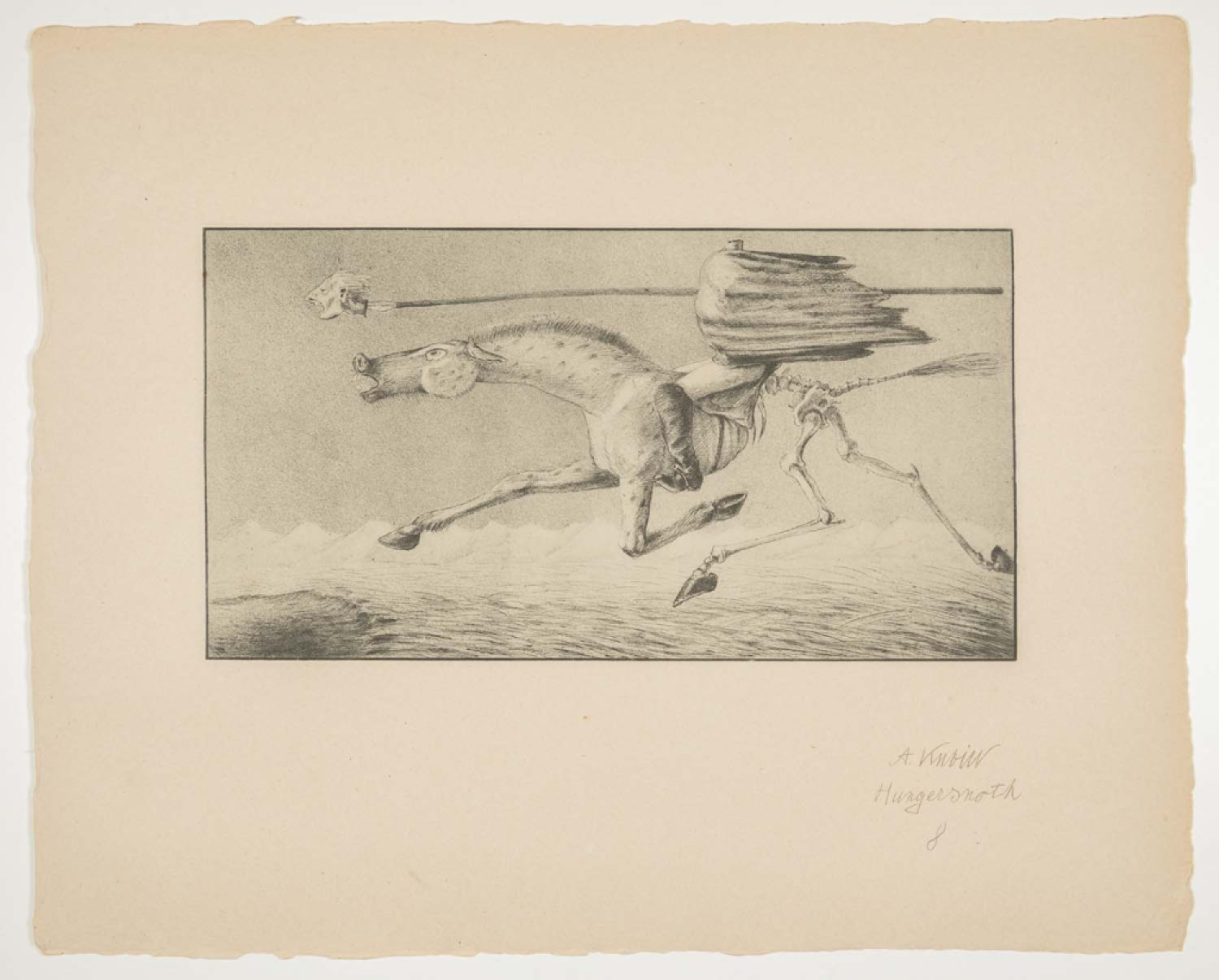

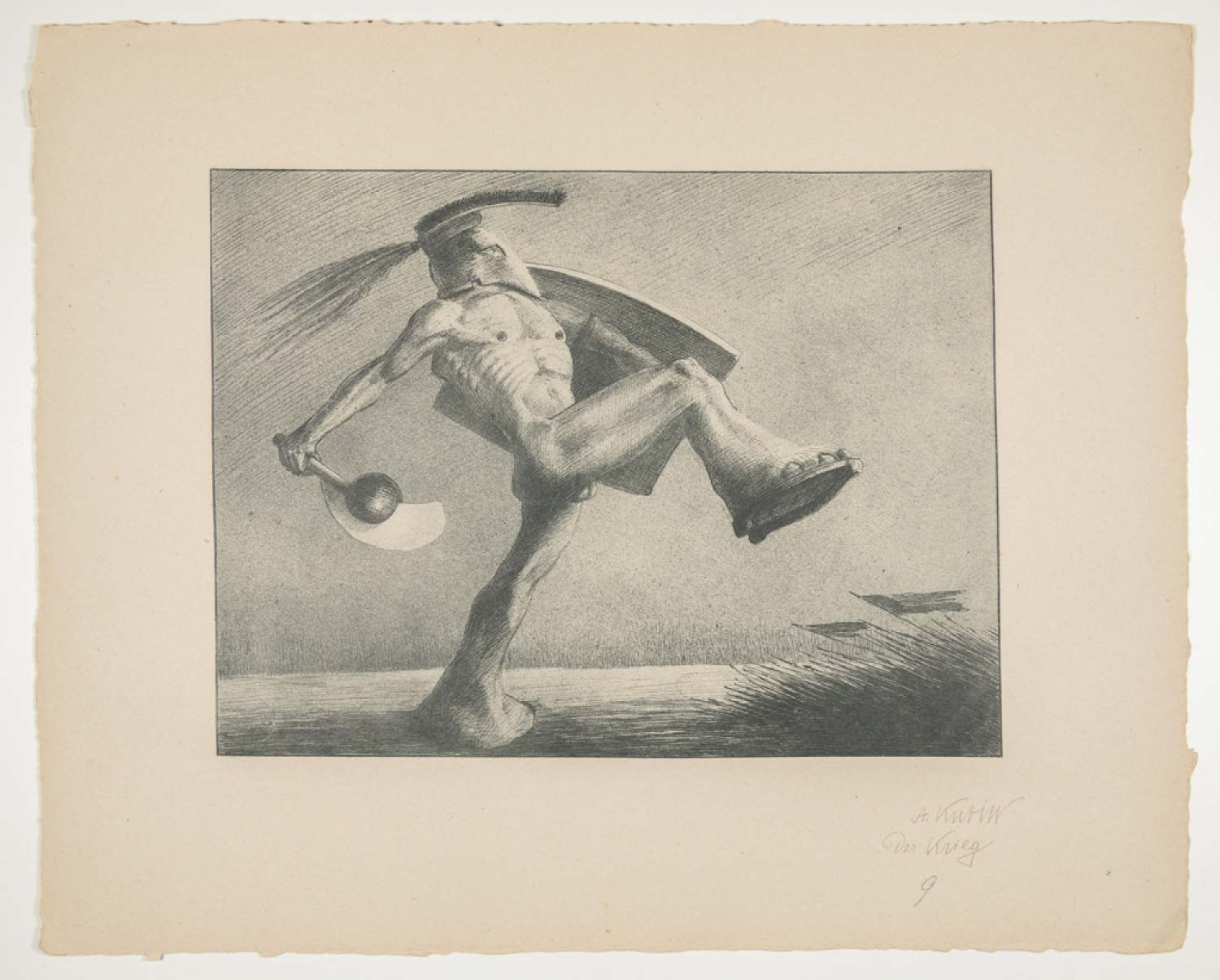

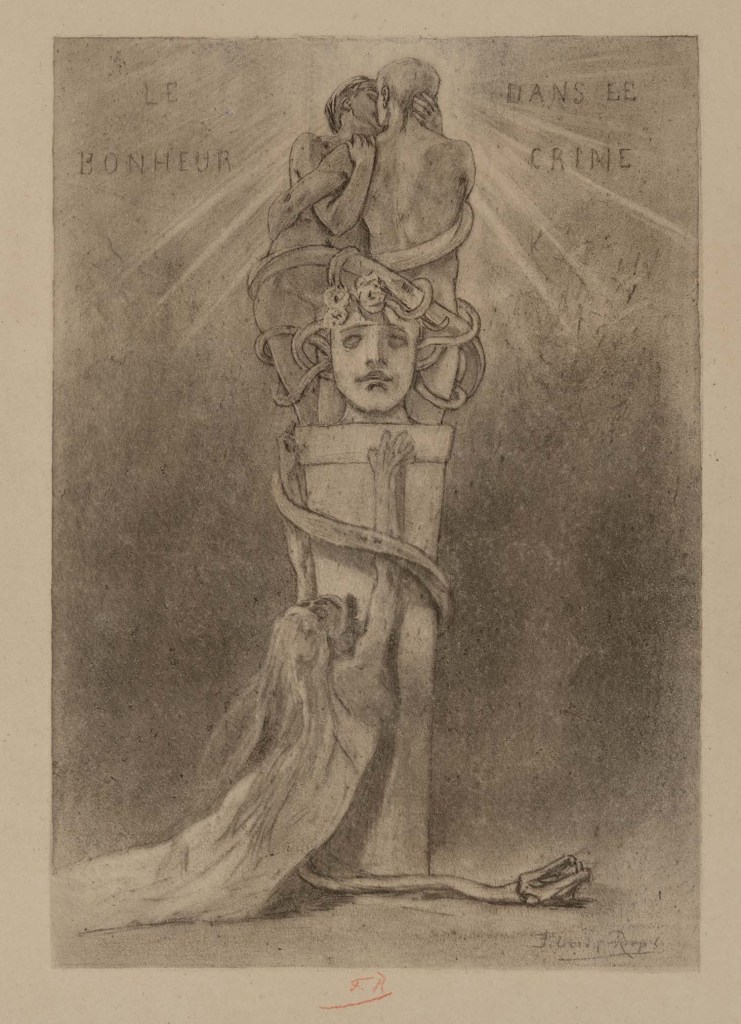

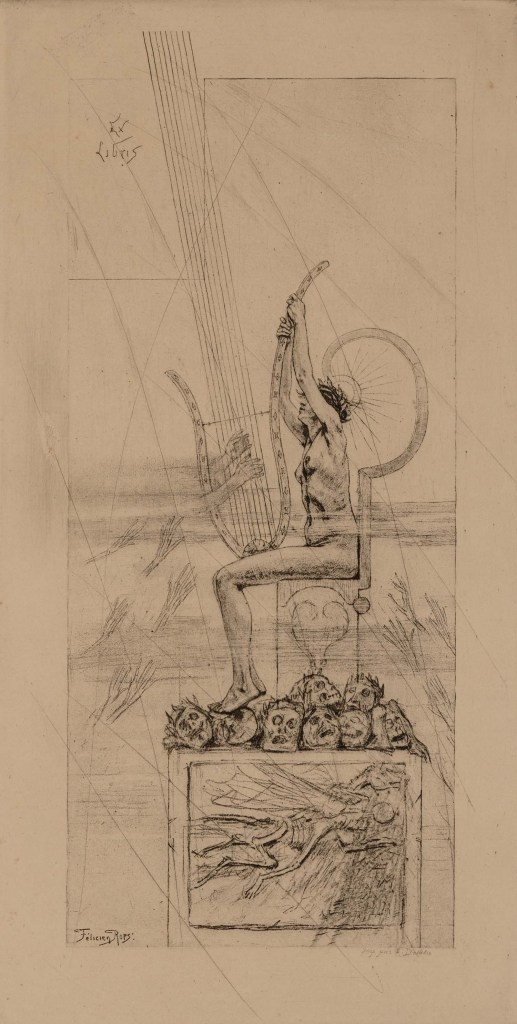

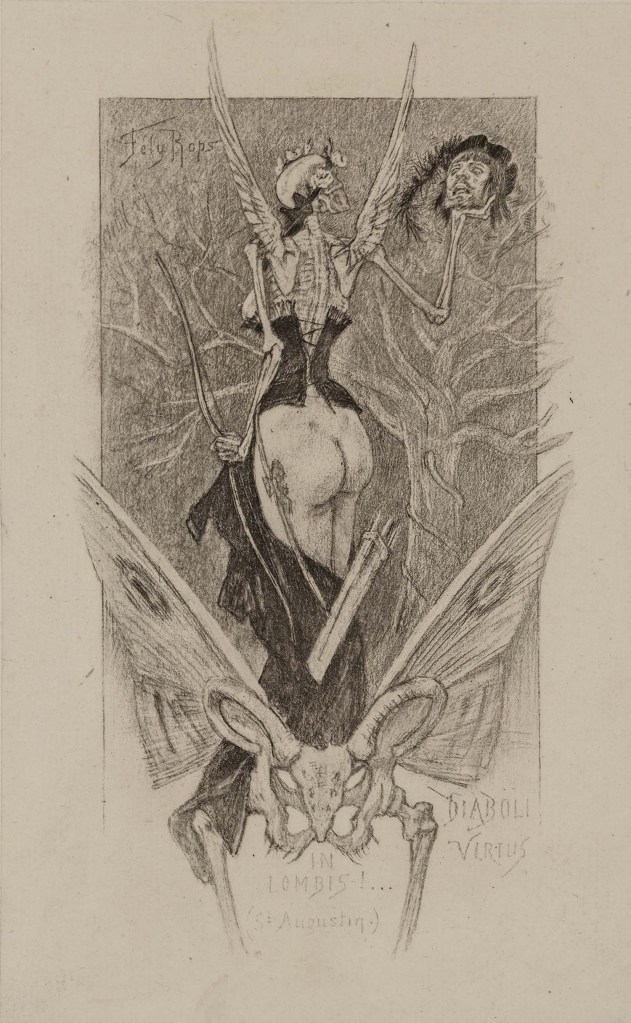

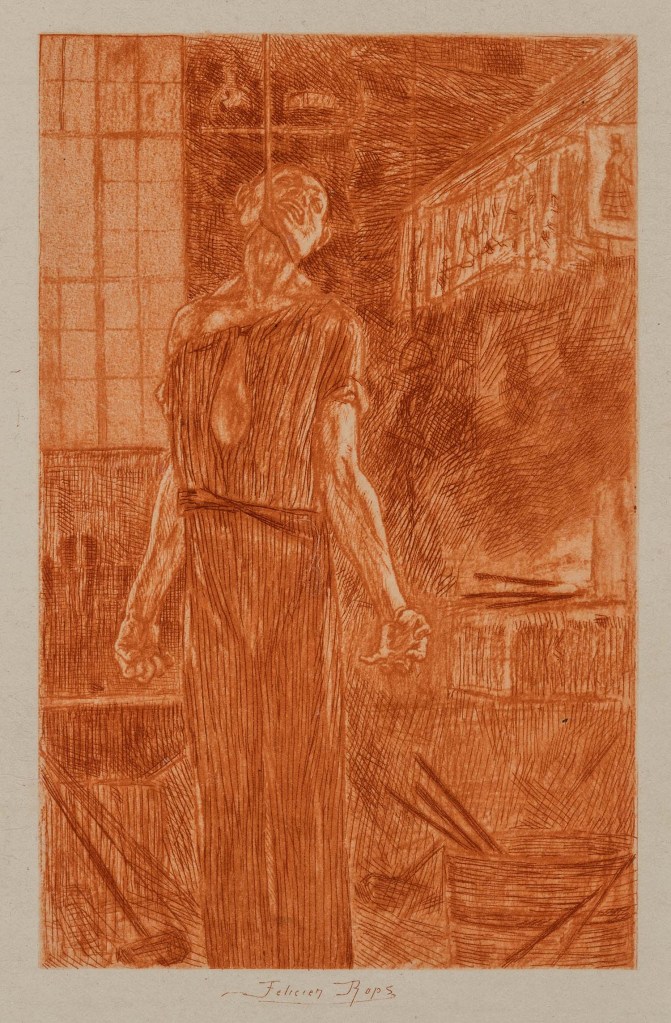

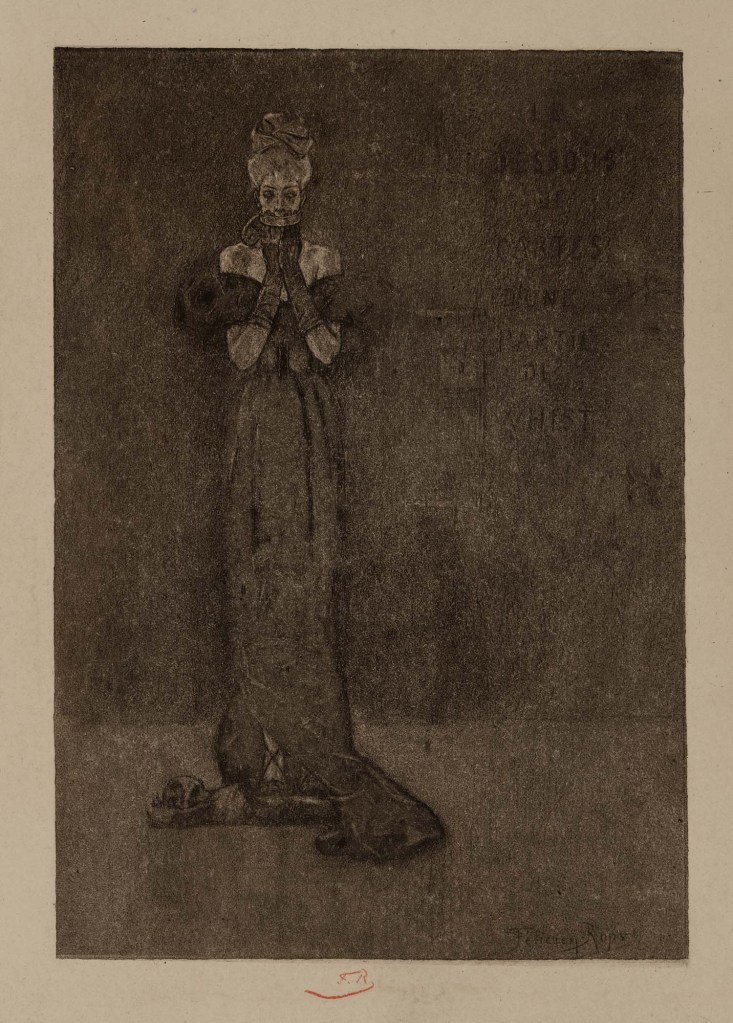

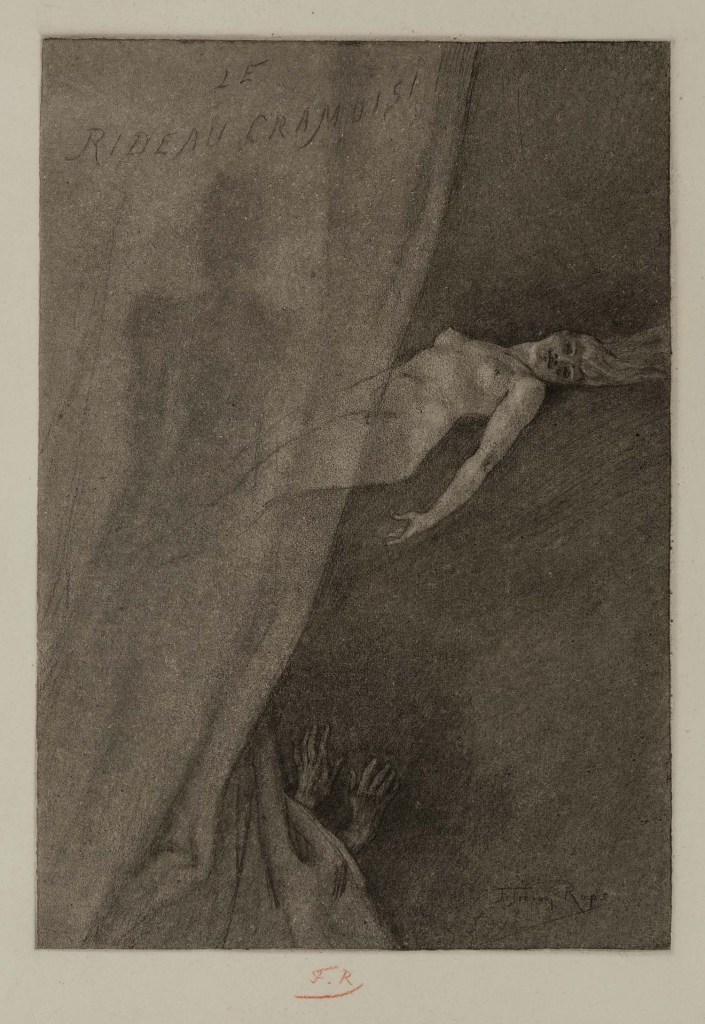

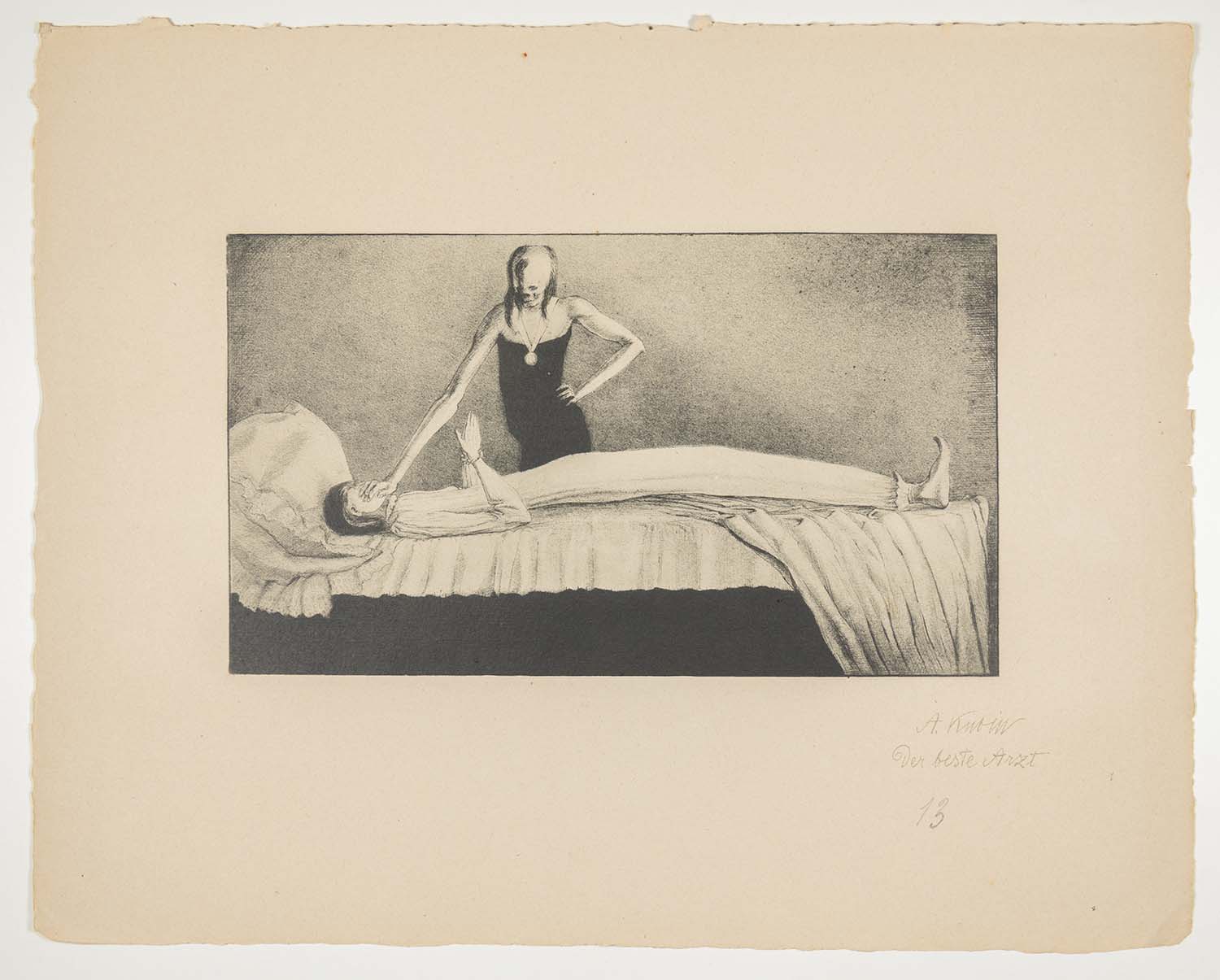

The show also benefits from the inclusion of several small and understated etchings by the lesser-known but intriguing Belgian Symbolist Félicien Rops, whose work here somehow juggles matters of elegance, eroticism, and mysticism. One wall of the show is devoted to the dizzying succession of the Rops-influenced Austrian artist Alfred Kubin’s dark fantasies and symbolic misadventures.

In the center of the Davidson Gallery, almost more a lobby area or entryway than official gallery space, we find the central — yet also decentralizing — sculpture “Chair and Fruit,” by Italian Giacomo Manzù, circa 1947. Serving as an apt introduction to the reality-upending nature of the exhibition, at large, Manzù’s gilded bronze sculpture is a quirky mash-up of a three-dimensional still-life fruit arrangement, metalized, and a gilded chair. The mix doesn’t compute, by standard contextual rules, but follows the kind of inner irrational order heeded by most of the artists in the show.

In other sculptural left turns, famed Russian constructivist Alexander Archipenko’s Torso in Space appears as a sleekly rounded, winnowed-down impression of a reclining female nude, as if alluding to sea-life ancestry — and hints of mermaid-hood. Just above the conspicuous Archipenko sculpture, legendary sculptor Henry Moore is represented, like a ghostly sentry, not in his classic three-dimensional mode but by faint drawings of bones in the countryside. The bones are decidedly Moore-ish, accentuating the archeological touch points behind his sculpture gardening.

Nothing is quite as it seems, or necessary in place by conventional standards in Iconography of Dread. Ultimately, this is art about both dread and its opposite — exploratory imagination and re-channeling of dreams, which sometimes leads to breakthroughs in the existential/mental fog. Art is there, for the expressive taking.

Iconography of Dread: Symbolism to Surrealism is on view at Santa Barbara Museum of Art (1130 State St.) through May 21. See sbma.net.