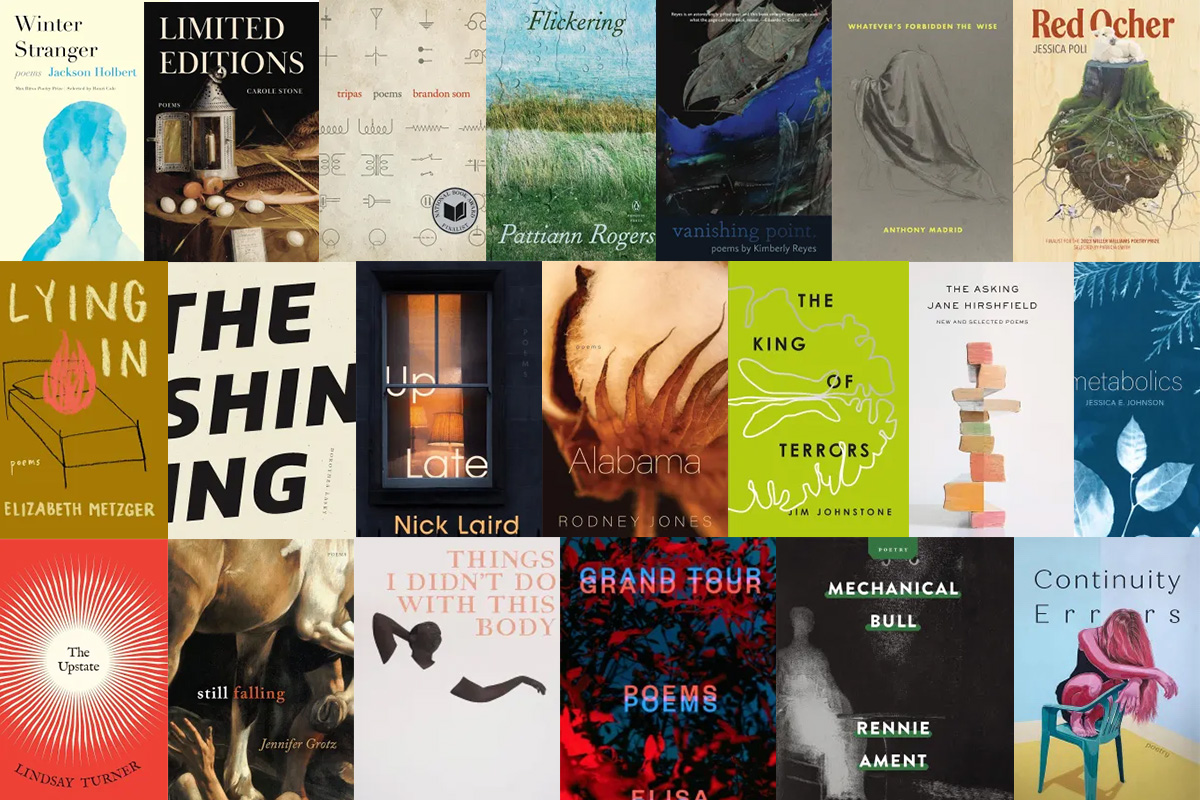

From Acre to Zagjewski: 31 Outstanding Poetry Books from 2023

Our Poetry Reviewer Picks His Top Titles for the Year

Every year, since 2014, I’ve set aside a couple of months to sit down with what amounts to a long shelf of books of poetry published in the past twelve months. My goal is to take stock of the art. It’s an ambitious and overwhelming endeavour, but I also consider it a great privilege to see what my fellow poets are up to.

It is a very time-consuming process. I begin by skipping around in each book, reading five or six poems to see if anything calls out to me. Those volumes that do are placed in one stack. Those that didn’t speak to me on the first go-round will get another look. Soon, I begin reading in earnest, steadily, from the opening poem in a volume towards its conclusion. Sometimes I’ll stop half-way through in a book that initially seemed magical but now seems less so. I rearrange my stacks, adding new favorites and removing those that didn’t quite pan out. While I generally recognize most of the poets’ names, I try not pay any undue deference to those who are especially famous.

Ultimately, I end up with 31 single-author volumes of poetry, one for each day in December. (Even then, I’m still switching books in and out at the last minute.) It’s a lot of poetry, but poetry is poorly reviewed in the U.S., and I would rather cast light on too many books than too few. Besides, my reviews are necessarily short. Ideally, they are windows into the volume’s form and content–just enough information to kickstart a reader into buying the book.

Over the years, I’ve occasionally included a volume because of its scope and brilliance, although I didn’t truly love it. That’s not the case this year. I can’t wait to return to each of these books, to revisit the pleasures they’ve already given me and to find new ones that I missed.

Mothersong by Amy Acre (Bloomsbury)

Mothersong lives up to its title’s promise: with a strong sideline commentary on absent fathers and the harm they wreck upon their families. Acre writes with an angry humor that’s hard to resist because of its brutal honesty, as in “Dead Disney Mothers”: “the good queen, mother of snow white: it starts and ends / here—acicular prick in a tall tower, bae bled cradleside // name unknown, mother of a deer: a swallowed sound / like the world’s choke, deadheaded on a douchebag’s wall.” Nevertheless, the general movement of the book is toward understanding and acceptance of the indomitable force of a mother’s love for her child, called out in the volume’s final poem, “T-Minus Zero”: “when she comes / you won’t remember if she cried / because / look / look at the day / arriving / someone is here.”

Mechanical Bull by Rennie Ament (Cleveland State)

Ament’s poems remind me a little of the absurdist fables of James Tate. Maybe it’s the sense of play apparent in titles like “Hildegard Von Bingen at the Beach” and “Murderer Walks Everywhere, Carrying a Grain of Self,” yet Ament’s world is wilder and less reality-adjacent than Tate’s. The opening lines of “Osip Mandelstam,” for example, are “Lone spine. Pomme de man. Poet del sol / met Stalin, ammoniated tampon.” Evidently the rule for the poem is that all words must be made up of letters from the title, which leads to some unexpected insights about the Russian poet, not to mention the Russian dictator—“ammoniated tampon” seems just the right sobriquet. And yet the poem is always on the edge of veering out of control: “A slap is a memo: spin. Ode to a noise. Ode / to a lemon. Ode to Osip, nimmed.” Funny weird, funny ha-ha, funny questionable, and funny good.

A Film in Which I Play Everyone by Mary Jo Bang (Graywolf)

Here are the first eight lines of “A Set Sketched by Light and Sound”: “Outside, there’s barking. The radio’s on / loud but no one is talking. The long day / is darkening. Two silver stars are parking / at the curb, a long silent line. Reading / Charles Lamb, on the truth: ‘They do not so properly affirm, as annunciate it.’ Like / an angel, I wondered? Like a Gabriel / telling a girl the facts of life.” Reading the poems in Bang’s new book is a bit like dreaming, or a bit like listening to someone think, or like remembering disparate events in one’s life, or, perhaps more accurately, like listening to oneself think about disparate memories from one’s life that have been filtered through dreams. In short, it is far from a logical and linear experience, but reading the book does what poetry is supposed to do: it helps us navigate the world in a new way.

Some of the Things I’ve Seen by Sara Berkeley (Wake Forest)

Berkeley’s day job is as a hospice nurse, and many of the precise, imagistic and sensitive poems in Some of the Things I’ve Seen allude to this work, which is both incredibly draining and infinitely fulfilling. In “Hospice Nurse,” she tells us that “When I show up for death / I take off my thousand pound weight // so I go in light.” In “Strangers’ Doors,” she admits, “Fear keeps me tall / and knowledge keeps me slow and still, / treading gently,” though she is honored to “stand witness / in the bethel of their suffering / and in the sanctuary of their ease.” Ultimately, the lessons she learns can be summed up in the last words of a dying patient: “Everything. Alright.”

Feast by Ina Cariño (Alice James)

Many of Cariño’s poems are concerned with the uses and abuses language, in particular, the adoption of a English by a Tagalog speaker. Not surprisingly, process can be traumatic: “I dream in a different dialect / sift my mother’s stout syllables / plump honorifics / from the language of my colonizers / what is left? / glossy contractions / shiny / subjunctive / grammar that belongs / to the anthropology of the pale.” Race and language are inextricably intertwined in Feast, and Cariño’s mordant sense of humor often shines through even when the situation is grim. After an evening with her white boyfriend’s racist parents, for instance, she decides that the milk smell of white people, lauded by “a brown sister,” isn’t so wonderful after all: “when milk turns sour ferments blooms fetid under the nose / the only thing to do is pour it down the drain.”

Sweet Shop: New and Selected Poems by Amit Chaudhuri (NYRB)

There’s a lot of humor in these poems from nearly forty years of writing. One of my favorites is “Our Parents,” which begins: “How embarrassing they are! / Some of their views / can be extraordinary. / Increasingly, we were torn / between protecting and / disowning them / for at least fifteen minutes.” That same humor, filtered through a more refracted lens, can be found in an extended series of Questions and Answers. “Q. How do you know if you’re an experimental filmmaker? A. If, after decades of making cinema and receiving acclaim and honours, the Damocles of uncertainty hangs on you as you begin your new film just as it did when you’d made your first, if there is no guarantee that it will be shown in cinemas or even seen, you can conclude with some certainty that you’re an experimental filmmaker.” Of course that desire to push past boundaries without any assurance of reward applies equally to a poet like Chaudhuri who, fortunately for his readers, does not shy away from risks.

Standing in the Forest of Being Alive by Katie Farris (Alice James)

Standing in the Forest of Being Alive began as a prize-winning chapbook, and the book-length version retains the original’s intense focus. The subject matter is grim—during the pandemic and Trump’s presidency, “six days before [her] thirty-seventh birthday,” the poet learns she has breast cancer—but her account of her treatment and mastectomy is studded with humor and passion, as in the opening lines of “An Unexpected Turn of Events Midway through Chemotherapy”: “I’d like some sex please. / I’m not too picky.” Good poetry seldom doubles as good instruction, but Farris’s poems provide a solid guide to how one might survive cancer and even thrive in the face of its myriad challenges and terrors.

Grand Tour by Elisa Gonzalez (FSG)

“Reader, I want you to know you are reading a poem,” Gonzalez writes. “What is the point of talking otherwise?” Originally, I misread point as pain, and that makes a kind of sense as Gonzalez writes frequently about the subject, whether it be heartache or her abusive father or the death of her brother, to whom the book is dedicated. Yet she writes with equal passion (and precision) about everything from the joys of sexuality to a hawthorn tree felled by an ice storm: “Over the carcass roamed / my ungloved palm. / My tender, curious fingers.” We may no longer judge poets by the elegance of their verse, and that’s a shame, for Gonzalez’s poetry is as graceful as it gets.

Still Falling by Jennifer Grotz (Graywolf)

In her book’s final poem, Grotz, Director of the Breadloaf Writers’ Conference, quotes Robert Frost without mentioning his name: “Earth’s the right place for love.” Frost’s poem, “Birches,” continues: “I don’t know where it’s likely to go better.” Grotz’s poem ends with these lines: “This world, the living, the mind where / the literal and figurative collude. Not death / where darkness and silence and dust are / only darkness and silence and dust.” It’s an instructive difference. Frost dismisses the question with a casually calculated—and very catchy—Yankeeism, but Grotz doesn’t take the easy exit. Instead, her poem, “In Sicily,” like so many of the others in Still Falling, nudges at and beyond the edges of perception in language that is gratifyingly grounded in the real world.

Things I Didn’t Do with This Body by Amanda Gunn (Copper Canyon)

Like many poetry books published this year, Gunn’s Things I Didn’t Do with this Body tackles serious subjects: race, sexuality, gender, aesthetics, societal and personal depictions and interpretations of the body, and any number of other Big Themes; Gunn handles this repertoire with skill, verve, intelligence and wry humor. And yet what I love most about this collection is the granular details of her memories and descriptions. I wish I could quote the prose poem “Shalimar” in full, but I’ll settle for the middle part, after the protagonist has learned she has cancer: “Each day she woke, bracing herself for the smaller disasters of dying. A broken foot, a snapped finger, the Tareytons she had to give up. She held her Bible and prayed until morning wore itself thin, through soap operas and mock judges, through Wheel of Fortune and the news.”

The Asking: New and Selected Poems by Jane Hirshfield (Knopf)

Like Charles Wright, Jane Hirshfield in some ways keeps writing variations of the same poem, over and over, book after book, year after year. And like Wright, she benefits enormously from the fact that the poem she keeps writing is so damned good. The work of both poets is deeply spiritual, but Hirshfield, a Buddhist, tends to focus inward, on the insights that can be gained from meditating on a limited group of objects or moments. Like Zen koans, her poems’ “meanings” often aren’t obvious, although there is clearly something to be learned from each of them. Take “A Day Is Vast,” from 2011’s Come, Thief: “A day is vast. / Until noon. / Then it’s over. // Yesterday’s pondwater / braided still in my wet hair. // I don’t know what time is. // You can’t ever find it. / But you can lose it.” Over the course of a large, career-spanning collection like this one, these little poems accrete like a coral into a reef that is magical and magnificent.

Winter Stranger by Jackson Holbert (Milkweed)

The environment described by Holbert in Winter Stranger is one of working class lives, pills and incarceration; dangerous rivers cut through the landscape; young men “bucked / hay our skin was hard we touched our palms / together speeding down the highway we turned / the headlights off and felt a little holy we were strong / but we were thin we slept on couches / we tore rotten stumps with our big hands.” It’s a vivid, enclosed, mostly rural world, and the content would be more than enough to make for a strong debut, but Holbert has also managed to absorb the formal lessons of entire schools of poetry, so that there are not just echoes of those he namechecks, like C.D. Wright and Adrienne Rich, Rilke and Éluard, but also Seamus Heaney, the greatest poet of the past fifty years, who has seldom had an acolyte so thoroughly absorbed by yet strangely free of the Master’s influence.

Metabolics by Jessica E. Johnson (Acre)

Composed of longish sequences mostly consisting of prose poems, Metabolics covers a range of topics in language that is both allusive and concise. Of smartphones, Johnson writes: “We used to place the telephones in cradles but now they are no longer baby-like no they are thin portals to vast streams the way in dreams a small thing unlocks something very large.” Of motherhood, she writes: “Despite so many attempts to resolve this tension, sometimes you are you and also sometimes mother just as light can be both particle and wave.” The poems are weighed down with the heaviness of being human on a post-hope planet, but there are still moments of guarded optimism, as in the final two lines of the book: “Sometimes the center isn’t you. / Or you are something more than you imagined.”

The King of Terrors by Jim Johnstone (Coach House)

Early on in The King of Terrors, the terror is the Covid pandemic: “First there was fear. Fear of being shut in, a continent of shut-ins, shut up. // Fear without breath.” But soon enough the book’s central terror emerges, a meningioma—a slow-growing brain tumor—along with the author and his doctors’ attempts to deal with the malignancy. Johnstone’s poems often contain a great deal of white space, which makes sense, considering how empty the present and future often seem to cancer patients. And rarely has a poet written with such insight and precision about the surgical process itself: “Take the stones from my pockets / and suspend me // headfirst // in artificial sleep. / Shake my temples dry. // On the table I’ll be given a choice: to finish, noun and verb, // or return— // snowfall brushing away the past, / the present, these words.”

Alabama by Rodney Jones (LSU)

Jones has chosen an apt title for his book. While he currently lives in New Orleans and occasionally mentions the city, he was born and raised in rural Alabama, and this volume is very much a bildungsroman about Jones’s transition from dutiful farm boy to a devotee of Jung and existentialism and the much-celebrated poet he is now. Still, his country upbringing is never far from his memory and aesthetic concerns. Imagistic free verse poems are interspersed with brief, untitled, italicized prose memories. In one, Charles Simic refers to him as “peasant poet.” While Jones jokes that he prefers the term “postmodernist outdoorsman,” he clearly takes delight in his roots. You can hear that tongue-in-cheek pride in another prose anecdote: “1976 I am teaching the sonnet to high school juniors. One says, ‘We can’t do this. It’s too hard. We’re not from New York. We’re from Alabama.’”

Up Late by Nick Laird (Norton)

There are plenty of strong poems in Up Late, poems about the night sky in Tyrone and talking to the sun in Washington Square and Sesame Street and our impending environmental catastrophe, with “all the experts / flabbergasted at how the losses multiply, and wait to devastate, and the wheels // are coming off this thing.” But they all pale in comparison to the title poem, a lament for the death of the poet’s father, surely one of the major elegies of this century. Partly the poem’s brilliance is due to Laird ability to evoke his father in relatively few words—“After your stroke you were born once more / as smaller, greyer, softer, and after Mum died, / left bewildered, adrift, ordering crap online / and following the auctions, the horses, the football, / the golf.” Just as important, though, are his reflections on the form itself: “An elegy I think is words to bind a grief in, // a companionship of grief, a spell to keep it / safe and sound, to keep it from escaping.”

The Shining by Dorothea Lasky (Wave)

“Icky lousy horrible dread / Is what I feel every day of my life / So I wrote a book so scary / It would mimic real life / In all the worst ways,” Lasky writes in “Going through a Mountain,” and there are certainly moments of great discomfort and fear in her latest book. But there’s a great deal of dark comedy, too. How often, for instance, does a poet use the adjective “icky” to modify the noun “dread”? I chuckled often at Lasky’s use of colloquial language to undercut pretension. In the beginning of “Twins,” for instance: “Man in an Easter suit / Leans into me / To kiss me // But I am not in the mood for that.” And the climax of the dreamlike “Blue Hallway”: “I am painting an orange / Suddenly someone gasps / ‘An orange is genius!’ // Then I start crying and crying / I’ve always secretly known / That I was a genius // I was just waiting for this moment / All my life I was just waiting / To be in this hell here.”

Whatever’s Forbidden the Wise by Anthony Madrid (Canarium)

The English-language poetry scene is currently dominated by book-length sequences with high-flown philosophies, so a poet who rhymes, and one who does so with a ribald, sometimes nonsensical sense of humor, is the true rebel of the moment. Such a poet is Anthony Madrid. In “Once Upon a Time,” he riffs on Prince’s “When Doves Cry”: “Maybe I’m just like my mother. / She’s never satisfied / Maybe I’m just like my father: / Always a bridesmaid, never a bride.” The next stanza ups the ante: “Maybe I’m just like my cat: / Licking invisible balls. / Perhaps you’ll reflect upon that, / Next time you’re screening your calls.” There is some true balderdash in this book, but like a Shakespearean fool, Madrid has plenty of useful counsel to offer on the sly. If you’ve been waiting for the contemporary heir to Edward Lear, wait no longer.

Lying In by Elizabeth Metzger (Milkweed)

“You want to know what I actually love?” begins the poem “Marriage.” “It is the mind I don’t have access to.” It’s an intriguing statement, yet one Metzger seems to be writing against throughout Lying In. Instead, her goal seems to be to inhabit the world through the eyes (and bodies) of her children, her parents, her husband. She manages this feat through her powerful imagination, which allows her to insinuate herself into the lives of those she cares about, though it is nearly always in an unorthodox fashion. In “For My mother Wanting Children,” the speaker admits, “Once or twice I dreamed you asked me / to open some incision / and tuck myself in. The worst part was // I had to fit. The best part was you were a body.”

perennial fashion presence falling by Fred Moten (Wave)

“Some ekphrastic evening,” Fred Moten writes in “epistrophe and epistrophy,” referencing both the rhetorical term and Thelonious Monk’s classic composition, “this’ll be both criticism and poetry and / failing that fall somewhere that seems like in between.” Indeed, Moten’s latest book is full of ideas and ruminations in a variety of registers. It’s a big physical object with even bigger philosophical and aesthetic aspirations. By turns tender and grating, comic and melancholy, this may be the closest thing to jazz alphabetic language is ever likely to get.

Red Ocher by Jessica Poli (Arkansas)

The book contains eleven centos, quite a lot of borrowing for a first book, and yet even in these poems of appropriated lines, we hear Poli’s voice, which, to paraphrase one of her poems, might be described as Pennsylvania backwoods elegiac. My favorite poems, though, are composed by Polis herself: “The Morning After,” about a duck bursting from the narrator’s hands after its head is cut off; “Ode to Seventh-Grade Girls,” in which, after her period stains her clothes, the narrator’s classmates, shield, rather than shun her; and “On Desire,” where the narrator and her friends are told press their ears to the ground to feel the blast of a miners’ charge, and “the dirt rose / against our faces— / a small wave hurrying / through the earth, / a short, chaste kiss.”

vanishing point. by Kimberly Reyes (Omnidawn)

It’s easy enough to experiment for experiment’s sake, but in vanishing point. (the period at the end of the title is very much intentional) Reyes’s assays beyond traditional poetry-making are clearly in service of a larger goal, the re-creation and repudiation of history’s injustices. vanishing point. includes color FBI sketches and black and white etchings, and three times in the book, you turn the page to find a QR code that takes you to a video poem on YouTube. Reyes also makes extensive use of dark and light gray to emphasize irony and erasure, so that readers must strain their eyes to recover text that has been or is being expunged from the historical record. Additionally, her many residences and fellowships, including a Fulbright in Ireland, enrich the book’s already bountiful content.

Flickering by Pattiann Rogers (Penguin)

With all signs pointing to pending climate doom, more and more poets have taken to writing about the natural world as though it were a subject newly relevant. These latecomers seem a bit, well, jejune, when compared with Pattiann Rogers, who has been investigating the science of creation and extinction for more than forty years. In her latest book, Rogers continues her winning mix of observation, information and imagination. Flickering is full of examples of her craft, but I’m especially drawn to the opening lines of “The Extinct, Giant Creatures of North America”: “They were here, all right, the bone-weight, / reek, and sheer of them, the tremor / of their presence stirring in daylit water / or moonlit water—crocodiles with curved / spikes like oxen horns; four-finned beasts / with round elephant bodies, lizard eyes, / rows of razor teeth, necks 23 feet long.”

Your Kingdom by Eleni Sikelianos (Coffee House)

“You know that science metaphors matter,” Sikelianos states towards the beginning of Your Kingdom. And towards the end: “language / is a lingering we keep hoping will draw / up exigence like water / from a well, metal / dust toward magnetite.” In between, in this ambitious book that reads like a book-length poem, we are shown, again and again and again, how—through language—humans can access “the brimming bag of time” and connect with every step of evolution and the biological world: “all the syntax in mouse song sounding out some- / where between bird-syllable and your thumb scrubbing a glass clean.”

Tripas by Brandon Som (Georgia)

Family is the central unit in Tripas, especially the poet’s Chicana grandmother and Chinese American grandfather and father. Their stories intertwine throughout the book, are are told in poems that are ambitious yet carefully wrought. Whether it is memories of his family’s store—“At his register, my father kept a ballpoint / for IOUs & cashed checks tucked / behind his ear”—or his grandmother’s years of working in a Motorola plant amid “chemicals that poison, cause cancers, / numb the senses of smell & taste”—Som weaves together disparate narrative and biographical strands into saga that feels both contemporary and timeless.

Limited Editions by Carole Stone (CavanKerry)

Throughout Limited Editions, Stone, like her great predecessor Jane Kenyon, finds solace in the quotidian. The poems’ speaker admires “ceramics / in cabinets, on shelves”; she enjoys walking “in the park, / pass the bocce court, / the fenced-off playground”; she takes pleasure in television “Mysteries—the detective / and his sidekick, a man and a woman, // attracted to each other” though they “never sleep together.” In “Be Happy,” she watches as “Steam rises from the teakettle, / a car starts up—a neighbor going to the 7-11.” It’s all so mundane, and yet even as she pours “grief into a wineglass,” the speaker reminds herself of “the beautiful children // in strollers I stop to ogle. The yellow forsythia, the peonies deep red, suddenly here.”

The Upstate by Lindsay Turner (Chicago)

“It was always a little like an outpost here,” Turner says of Upstate South Carolina, “The sun is big behind the smog / You fill out forms and then you die.” It’s a place of “dogfights in the mountain country where they found the dog beside the road / the edges turning yellow, strain in the house and over it.” But the poems in The Upstate move far beyond the northwest corner of the Palmetto State; in fact, Turner is one of those poets who appears capable of turning just about any observation or experience into a successful poem. At the end of the book, her simmering argument with capitalism explodes into a paroxysm of rage: “The money fishing in your toxic money Breathing / In your bed The money till it suffocates Is separated / By your money Is detained by it and for it Is mined / Is killed for.”

The Gentle Art by William Wenthe (LSU)

The Gentle Art records the poet’s journey in search of the truth about the brilliant and cantankerous American artist James McNeill Whistler. The title riffs on a volume of Whistler’s correspondence, The Gentle Art of Making Enemies, and the poems combine incidents from the artist’s life with Wenthe’s own observations and memories. Perhaps some of the longer pieces struggle a bit to fit biographical details into the constraints of verse, but there is some lovely writing in here, no more so than in the final lines, when Wenthe suggests that all of us, rather than looking for other half, “in the story / Plato put in Aristophanes’s mouth,” instead actually “spend / our days in search of our perfect / sorrow, suspecting that love’s / the likeliest place it would hide.”

The History Hotel by Baron Wormser (CavanKerry)

I have been reading and enjoying Wormser’s poetry for decades, though I’m not always sure just why. His speakers often seem to resemble himself: an intelligent, self-sufficient white man who has read widely (Wormser was a librarian for twenty-five years), and whose personal problems mostly seem solvable. The occasions for his poems vary greatly; indeed, they are notable for the lack of the single overarching obsession that has driven many poets to do their best work. And yet, poem by poem, there are nearly always lines or images that suddenly shock the work to life. In the title poem, for instance, Wormser writes of “October, the season of dying disappointments, / Beloved of gravediggers, poets, and dog walkers.” That’s a nifty and unexpected trinity, the sort of surprise found throughout The History Hotel.

Continuity Errors by Catriona Wright (Coach House)

Like a post-industrial feminist Rodney Dangerfield, the speaker in the poems of Continuity Errors can’t get no respect. In “Party On,” a female contingent faculty member surrounded by whingy angry men is somehow forced to play the improv comedy game of “yes and.” In “Species Loneliness,” the speaker, “like everyone else,” uses trees / as a metaphor for myself,” but those metaphors simply show “how bent / I’ve grown, how straggled my crown, how I gorge / my nutrients only to throw them back up.” And in “Surrender,” she happily gives herself up to the aliens who have come to claim her: “Tractor beam, whenever / you’re ready. // Clouds, please part / me from residual fear. // Cornfield, leave / no trace of my exit.” Wright balances deadpan humor with evident despair—a brilliant performance.

True Life by Adam Zagajewski (FSG)

Published in Polish in 2019, the work in True Life appears in English two years after Zagajewski’s 2021 death and feels like a gift from the recent yet irrecoverable past. Translated by the inimitable Clare Cavanagh, the poems are short—rarely longer than a page—and showcase Zagajewski’s low-key sagacity and trademark wit. Even outstanding books of poetry typically have their peaks and valleys, but this collection offers one strong effort after another, delivering “wisdom / (without resignation) … / a certain calm madness… / a moment’s joy / and melancholy’s dark contentment.” Rather than late work by a poet past his prime, the poems in True Life have all the energy and verve of someone just starting out, with his entire life ahead of him.

This review originally appeared in the California Review of Books.

You must be logged in to post a comment.