Grave Disability Law Poses Grave Problems for Santa Barbara County’s Mental-Health System

County Agrees to Delay Implementation of New State Law That Could Expand Involuntary 5150 Holds Tenfold

In a head-on collision between good intentions and the stubborn facts of life — and death — on the streets, the Santa Barbara County supervisors voted to defer implementation of a new state law that would greatly expand the number of people who can be held against their will and forced into involuntary treatment for severe substance-abuse issues. In addition, the new law — Senate Bill 43 — would allow the county to hold and treat people against their will if they can’t provide for their own health care and medical treatment.

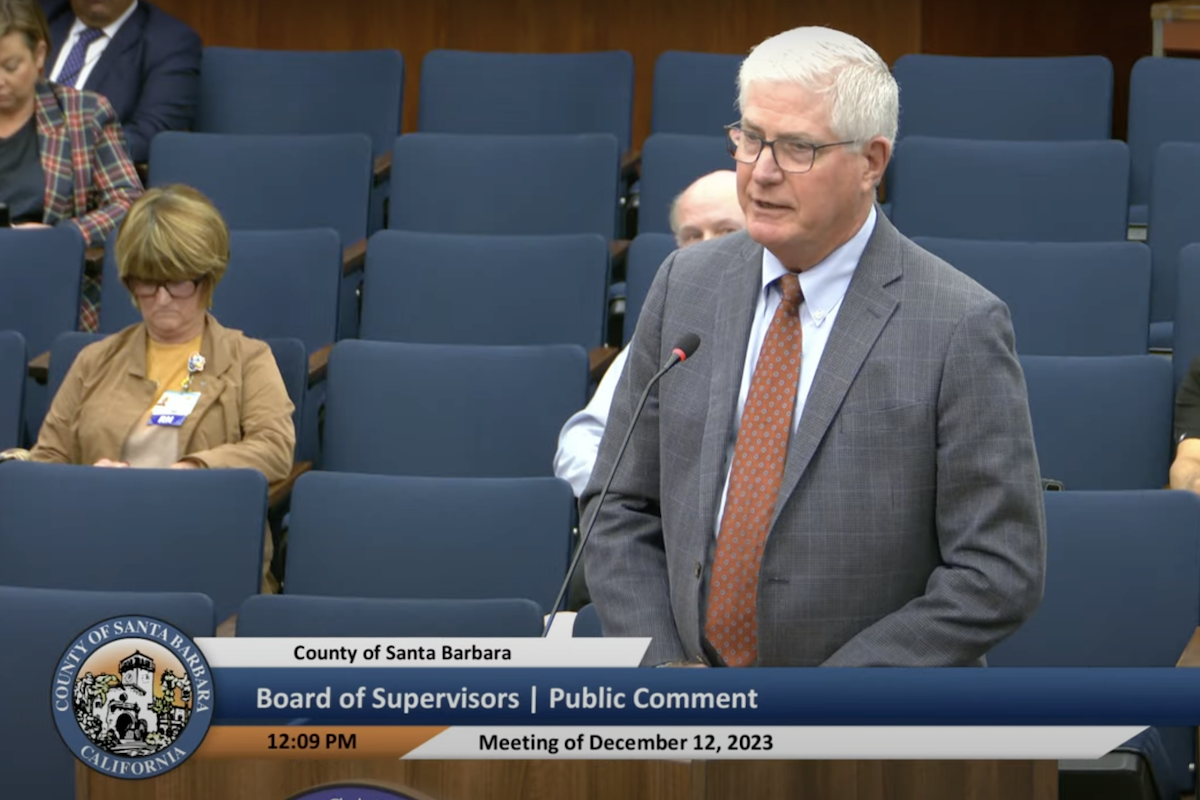

If implemented, these changes would expand by tenfold the number of people currently held for treatment against their will than the current law allows, stated Toni Navarro, chief executive for the county’s Department of Behavioral Wellness. Last year, Navarro said, 425 people in Santa Barbara County were placed on what are called 5150 holds. The county has only 16 beds for such holds. If that number were to increase to 4,250, the supervisors were told by an executive team dispatched from Cottage Hospital — including CEO Ron Werft — the emergency rooms would be overwhelmed, and chaos would ensue.

The law that authorized such holds has not been amended since it was first enacted 55 years ago. The new law — unanimously approved by both houses of the state legislature and signed in October by Governor Gavin Newsom — seeks to address the upwelling of addiction, mental illness, and homelessness engulfing California’s cities by expanding what qualifies as “gravely disabled.”

While Navarro said she supported the law’s intent, she asked the supervisors to wait until 2026 before implementing it. Her department, she acknowledged, was already under stress. Early next year, the supervisors will be examining how the delivery of crisis services can be improved. At the very least, Navarro said, she needs time to craft a plan and to hire the skilled staff necessary to make it happen. That’s not possible by January 1, 2024, when the new law goes into effect.

Already 38 counties have indicated they intend to defer implementation. The latest startup date allowed by the legislation is January 1, 2026. Even then, it will be a stretch. The big hang-up is where to send people involuntarily held for treatment.

“These facilities do not exist in the state of California,” Navarro stated. “Anywhere.”

An even bigger stretch, she added, is whether involuntary treatment programs work in treating serious substance abuse. Based on her limited research — “Don’t quote me,” she said, only partially in jest — Navarro said involuntary treatment programs tend to yield higher rates of relapse, recidivism, overdose, and death. This grim assessment was later echoed by Dr. Paul Erickson, head of Cottage’s Psychiatry and Addiction Services Department.

“It’s an idea that has appeal,” Erickson said, “but it has not succeeded in any states that have tried it.”

Making the case for sooner rather later was Lynne Gibbs, mental health advocate and policy specialist for the National Alliance on Mental Illness. Gibbs dismissed Navarro’s prediction of a tenfold increase of involuntary holds as a “hysterical overestimation.” Behavioral Health, Gibbs added, “has a history of ideological opposition to any even temporary form of involuntary care.” Gibbs cited a handful of specific cases in which those experiencing extreme duress were not deemed 5150 worthy and later died or suffered dire consequences.

Supervisor Bob Nelson — moved by Gibbs’s testimony — expressed opposition to any delays beyond six months. Where were all the people going now, he asked one nurse with 45 years of ER experience, who would be creating so much chaos in the hospitals because of SB 43?

“They’ll be on the streets,” she replied.

The most conservative member of the board, Nelson is also the most open to coercive treatment. The county is spending millions on homeless care, he noted, but treatment remains a critical missing link. Some people will refuse treatment, he noted, and need to be pushed.

Ultimately, the supervisors voted 4-to-1 to give Navarro the two-year extension she sought but put her on notice that she needed to show up in July — six months from now — with a well-thought-out game plan.

“Sometimes you have to go slow in the beginning,” said Supervisor Joan Hartmann, “so you can go faster later on.”