The ‘Forrest Gump’ of Santa Barbara History

Joseph Chapman’s Story Is a Pirate’s Tale of Redemption

On November 6, 1822, the chapel bells hanging in the adobe-brick belfry of Mission Santa Inés rang out lustily in the middle of the day. Their chiming chorus announced to the wild countryside of the Santa Ynez Valley that vows had been exchanged and a union had been blessed.

It was a Wednesday, though it is unlikely the happy couple chose weekday nuptials to save money. The bride, Maria Guadalupe Ortega, was a daughter of one of the founding families of Santa Barbara. She was the granddaughter of Captain José Francisco de Ortega, who discovered San Francisco Bay as a scout for the Portola expedition, built El Presidio de Santa Bárbara, and stood as her first comandante. Captain Ortega would go on to receive 25 miles of Gaviota coastline in recognition of his service, a land grant he named Nuestra Señora del Refugio.

The groom? He was a pirate from Boston nicknamed “El Diablo,” who four years earlier had taken part in a violent raid on the Ortega Ranch.

As the message of the Mission bells resounded through the nearby Santa Ynez Mountains, the wedding guests, glass of Angelica in hand, must have had some stories of their own to tell about this deliciously scandalous match.

One favorite tall tale for this extraordinary romance began the day the groom was seized at Rancho Refugio during the infamous sea-pirate invasion of December 1818. Sentencing came swiftly: He was to be dragged to his death by ropes tied to horse saddles. That’s when the lovely young Maria, the belle of California, took a liking to the blue-eyed American in chains and convinced the Spanish corporal to stay the execution. It’s one of many legends surrounding Joseph Chapman, the first permanent English-speaking resident of Alta California.

Born in Boston the year the Constitution was signed, Chapman apprenticed as a carpenter and blacksmith, but he longed for the sea. He boarded whaling expeditions that took him down the Atlantic seaboard and then joined the crew of the Argentine ship Santa Rosa in 1817, which sailed round the Horn to Hawai‘i, known at the time as the Sandwich Islands. That is where Chapman’s story enters murky waters.

Popular accounts, and Chapman’s own side of the story, claim he was shanghaied into service in the Sandwich Islands by the dreaded Franco-Argentine pirate Hippolyte Bouchard. Bouchard, fresh from sailing for Napoleon against the English Navy, had crossed the ocean to fight in Argentina’s independence revolution against Spain, now boasting Argentine citizenship and letters of marque to attack Spanish ships and settlements.

Chapman, in this version, was the maritime adventurer turned reluctant buccaneer, forced into service by the cutthroat Bouchard. This story may well have saved his life when he made land in California. But a recently discovered document reveals Chapman voluntarily joined Bouchard’s freebooters and set sail for the Pacific coast on a Viking-like assault of the Alta California Missions and quest for the Spanish treasures kept within.

Willing pirate or not, Chapman didn’t seem particularly good at this work. Historical accounts of his piracy career diverge, but they all agree on one point: Chapman kept getting captured.

He was first mate on the Santa Rosa, while Bouchard captained his black ship Argentina with 350 men. Their first target was Monterey, the capital of Spanish California, and in the waning moonlight of November 20, 1818, the two ships quietly anchored off the coast. At dawn, the Santa Rosa opened fire on a garrison at the Presidio, who had been warned of the invasion, and Chapman’s ship incurred significant damage from their return volley.

While most of the crew swam to the Argentina, Chapman and two others rowed in to surrender and were taken into custody. But a few days later, Bouchard landed 200 men and raised the Argentine flag over the Presidio for six days before setting the fortress ablaze, pillaging the town, and reclaiming his prisoners, including Chapman.

Captain Ortega’s Refugio Ranch was the next raiding port of call, famed not only for its natural wealth but also for its reputation as a smuggler’s paraiso. Now Santa Barbara was on high alert, and Antonio Lugo, the mayor of Los Angeles, lay in wait with 50 men, with additional reinforcements assembling at the Presidio under José de la Guerra. Bouchard’s men stormed the ranch, and when they found all its treasures already removed to the Presidio, they slaughtered all the horses and livestock and then set an angry sail for San Juan Capistrano.

Chapman’s piracy days ended at Refugio cove. Some stories say he surrendered on the beach, some say he marched six miles over the mountains and surrendered at Mission Santa Inés, and others say he went ashore to find water with a fellow pirate named Tom Fisher, the first African-American man to set foot in California, where they were nabbed by Lugo. I suspect this was where his desperate claim to have been kidnapped in Hawai‘i saved his life, along with his experience as a carpenter and blacksmith.

Chapman’s swashbuckling skills were suspect, but his building skills soon became legend. And with ax, timber, and stone, he built up youthful Alta California and made his own path to redemption.

Antonio Lugo took his Yankee prisoner back to Los Angeles, where he put Chapman to work building adobe houses and felling timber in the San Gabriel Mountains. He was called “El Diablo” for his gritty language and his Shining-like fury when his axe met a sturdy oak — but soon the Angelenos also knew him as “Blond Joe” or “José el Ingles.” He supervised the construction of the first church in Los Angeles, which also loaned the burgeoning pueblo its name, La Iglesia de Nuestra Señora Reina de los Ángeles, dedicated in 1822 and still standing near Olvera Street in downtown L.A. During his time living in Los Angeles, Chapman was also the very first American citizen to plant a vineyard in California. But it was the grist mill he built for Mission San Gabriel that would bring him back to Santa Inés and Maria Guadalupe.

His San Gabriel mill was a New England design, with a brick water chute called a mill race that rotated a vertical waterwheel, which then turned two millstones to grind corn and wheat into flour. The padres of Mission Santa Inés coveted similar engineering for a fulling mill — which tightened and softened fabrics in a potent cocktail of urine and diatomaceous earth — so they borrowed Chapman, still on parole at Mission San Gabriel, for its construction.

It was likely at Mass one Sunday at the Mission that Blond Joe encountered Maria. One has to wonder how awkward those first courting dinners must have been at the Ortega Ranch he had once stormed on a bloodthirsty pirate raid. Perhaps the Mission fulling mill became his penance. The mill was completed in 1821, and in 1822 he was pardoned by the King of Spain, baptized at Mission San Buenaventura, and married to Maria Guadalupe Ortega at Mission Santa Inés.

If one of their wedding guests, back in November 1822, wandered out to the amphitheater of bluffs a few steps away from the bells of the Mission chapel, he would have just been able to make out, past the pear and olive orchards planted down the hill, the adobe tiles of Chapman’s fulling mill. It still stands as a symbol of a pirate’s redemption.

Adam McHugh became enamored with the history of Santa Barbara while researching his book Blood from a Stone: A Memoir of How Wine Brought Me Back from the Dead, which you can find online and at all the local bookstores. He lives in Santa Ynez now but used to live in the San Gabriel Valley, much like Joseph Chapman. Find him on Instagram @adammchughwine.

Premier Events

Sun, Apr 28

6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

AHA! Presents: Sing It Out!

Thu, May 02

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Things with Wings at Art & Soul

Sat, May 04

10:00 AM

Lompoc

RocketTown Comic Con 2024

Sat, Apr 27

11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Plant Fest

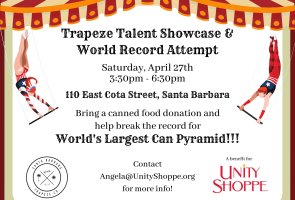

Sat, Apr 27

3:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Trapeze Co and Unity Shoppe Spring Food Drive

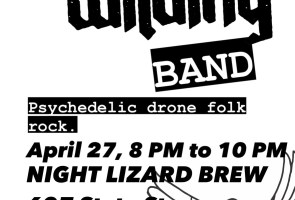

Sat, Apr 27

8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Beau James Wilding Band Live

Sun, Apr 28

11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Earth Day Festival 2024

Wed, May 01

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

American Theatre Guild Presents “Come From Away”

Thu, May 02

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

100th Birthday Tribute for James Galanos

Thu, May 02

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Meet the Creator of The Caregiver Oracle Deck

Fri, May 03

4:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Fair+Expo “Double Thrill Double Fun”

Fri, May 03

8:00 PM

Santa barbara

Performance by Marca MP

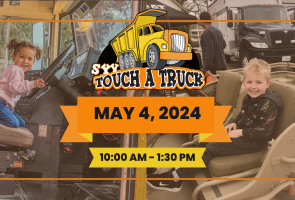

Sat, May 04

10:00 AM

Solvang

Touch A Truck

Sun, Apr 28 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

AHA! Presents: Sing It Out!

Thu, May 02 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Things with Wings at Art & Soul

Sat, May 04 10:00 AM

Lompoc

RocketTown Comic Con 2024

Sat, Apr 27 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Plant Fest

Sat, Apr 27 3:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Trapeze Co and Unity Shoppe Spring Food Drive

Sat, Apr 27 8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Beau James Wilding Band Live

Sun, Apr 28 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Earth Day Festival 2024

Wed, May 01 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

American Theatre Guild Presents “Come From Away”

Thu, May 02 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

100th Birthday Tribute for James Galanos

Thu, May 02 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Meet the Creator of The Caregiver Oracle Deck

Fri, May 03 4:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Fair+Expo “Double Thrill Double Fun”

Fri, May 03 8:00 PM

Santa barbara

Performance by Marca MP

Sat, May 04 10:00 AM

Solvang

You must be logged in to post a comment.