Dancing on Walls, Bridging Divides

Exhibition at UC Santa Barbara’s AD&A Museum Explores, Celebrates 20th-Century Dance, Working Across Cultural and Racial Barriers

UCSB’s AD&A (Art, Design & Architecture) Museum’s current major exhibition extends its attention yet further afield from art proper in the form of Border Crossings: Exile and American Modern Dance, 1900-1955.

What might seem, at least on paper, as something of a non sequitur — dance being a medium all about motion and bodily kinetics in real time, confined to the walls of a museum space — springs surprisingly to life in this flexible art space. As manifested by curator Ninotchka Bennahum, the show makes liberal use of archival photography, explanatory historical texts, occasional costumes, and the all-important source of filmed dance sequences through the decades.

The exhibition tells of a story in motion on multiple fronts as well as marginal zones creeping toward the centers of attention in the dance world. Walking through the galleries becomes a polyrhythmic pageant from many sources beyond the white culture, and delivers choreographic essence in the moment, beyond just the detailing of vibrant and revolutionary histories of key figures.

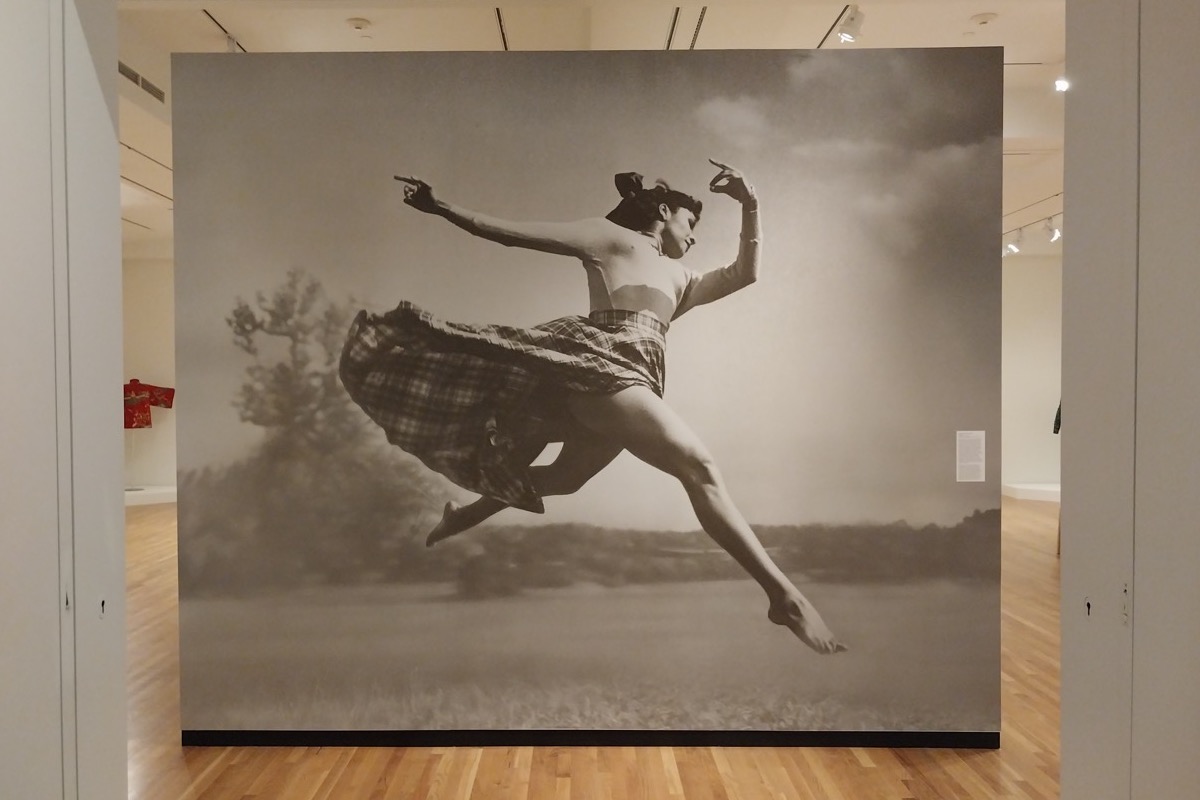

Perhaps the primary focus goes to Katherine Dunham, dancer and mover-shaker and spearhead of many dance groups and projects, including a role as director of the WPA Theater Division. Fittingly, her lithe, airborne body is seen in a vast photograph on a wall facing the main gallery entrance, and we learn of her extensive work in bridging cultural-racial divides in American dance. The House Committee on Un-American Activities gave her the inverted badge of honor of censorship and funding withdrawal after she played a lynched Black man in 1951’s Southland.

Prominent game-changers and artists are given due prominence in the show, which showcases the bold efforts of Modern Dance artists, choreographers, and activists from the BIPOC domains to break down prejudicial barriers, to “cross borders,” and also to redefine said borders. As choreographer Michelle Manzanales noted, “I am not crossing borders. People have drawn borders across me.”

Border Crossings manages to touch on many of the prominent hybrids in modern dance that developed early in the 20th century, including the oldest dance traditions in North America, the Indo/Hispánico/x dances of Native Americans. Dance gradually and then exponentially expanded its scope by incorporating traditions from Africa, Latin America, Spain, and those working in the vein of radical and civil rights projects.

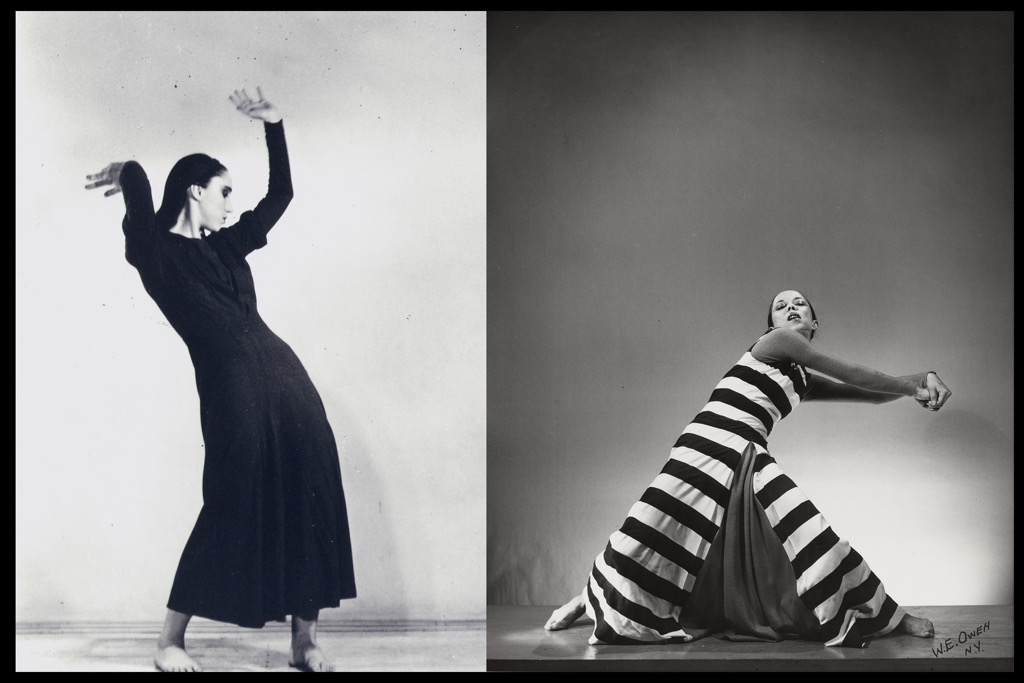

Pearl Primus was a Black activist choreographer and dancer, working very much within the parameters of the mantra of “dance is a weapon of social change.” Among her choreographic works were the charged ’40s dances Strange Fruit (based on the chilling Billie Holiday song about a lynching) and The Negro Speaks of Rivers. Referring to multiple issues, Anna Sokolow’s The Exile (A Dance Poem) addressed the Nazi invasion of Poland in 1939 as well as Mexico’s denial of 30,000 would-be Jewish refugees during WWII.

Telling quotes punctuate the visual displays in the show. Early 20th-century Black dance sensation Aida Overton Walker, seen in a striking photo of her 1911 performance of Salome, said in 1905 that “I venture to think and dare to state that our profession does more toward the alleviation of color prejudice than any other profession among colored people.”

Mary Hinkson, one of the four grad students as University Wisconsin — Madison who created the first interracial modern dance troupe in the ’40s and later joined Martha Graham’s company, said in 1951 that “we will have to speak of the ‘Negro dancer’ until people are finally considered only on the grounds of their talent and merit.”

Incurable seekers of local color (guilty as charged) will take delight in coming across Louis Horst’s dreamy photograph of Santa Barbara–bred dance icon Martha Graham, seen blissfully embraced by the apex of the Pyramid of the Sun at Teotihuacan, outside Mexico City. As she said of that journey, which takes on a dance-like visage in the photograph, “It was striking going up those steps and arriving at the top to be absorbed in a very hallowed place,” and also asserted that “a great deal of what I do today is not only American Indian but also Mexican Indian.”

Graham was one of many artists, in dance and other disciplines in the first half of the tumultuous 20th century, who recognized that some of the richest ideas and energy sources come from the confluence of life outside of presumed borders — geographical and internal.In a final analysis, through this fascinating exhibition, these museum walls speak truths and shiver with action, beyond the worlds of AD&A.

‘Border Crossings: Exile and American Modern Dance, 1900-1955′ is on view through May 5 at the UCSB AD&A Museum. The Museum is open Wednesday to Sunday from noon to 5 pm. See museum.ucsb.edu.

You must be logged in to post a comment.