Ordained Pastor Comes to Santa Barbara to Talk White Christian Nationalism

‘American Heresy’ Author John Fanestil to Discuss Ways This Strain of Christian Thought Has Taken Root in American Life

Unfortunately, the event on 2/25 has been cancelled due to illness.

White Christian nationalism has influenced American life in a multitude of ways, from how it was promoted by the Federal Bureau of Investigation to its role in the January 6 insurrection.

In the words of John Fanestil, an ordained pastor in the United Methodist Church with a PhD in American history from the University of Southern California, White Christian nationalism is a deeply rooted and distinctly American strain of Christian thought that produces what he calls “bitter fruits”: violence, nostalgia, racism, and propaganda.

It is a story of White racism, American nationalism, and Christian superiority perpetuated by White Christian Americans: the United States is in a privileged position over the other nations as if God has a preference for the U.S. and the white Christians who presumably founded it.

As witnessed on January 6, this way of thinking is in a season of “renewed flowering,” Fanestil says.

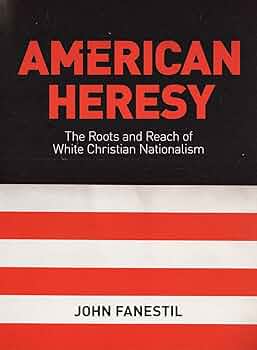

Fanestil is the author of American Heresy: The Roots and Reach of White Christian Nationalism, a book that explores the roots of White racism, political violence, and conspiracy thinking, tracing them to the early English Protestant colonization of North America.

Fanestil will be speaking at Santa Barbara First United Methodist Church on Sunday, February 25, at 6 p.m. He sat down with the Independent ahead of his talk to shed some more light on the enduring legacy of this “uniquely American brand of Christian heresy, which has always been a part of American public life.”

How is this way of thinking embedded in American history? Think of a tree with very deep roots and branches. And that tree goes through seasons of flowering, where it becomes more visible. So January 6 was just the fruit — I call them the bitter fruits — of what is deeply rooted in American culture.

For instance, I’m of the mind that I don’t think of Donald Trump as a particular outlier in American politics or American public life. I think he’s part of a very long, deeply held tradition.

You know, I’m 62 years old, and in my lifetime, you can go from people like Joseph McCarthy to George Wallace and trace this brand of religiously identified nationalism with strong inflections of White racism that have always been a part of the American public landscape. One of my key arguments is that what we’re seeing today should not be as surprising as people seem to find it.

You can trace it from slavery to Jim Crow to mass incarceration. That entire stream of our history is shaped by this religious background and this White racism, which is not an authentic expression of the Christian faith. But many Christians have embraced it as such. Hence the title, American Heresy. Those are heretical Christian ways of thinking, but they’re very American ways of thinking.

How do you think this affects the perception of Christianity or the Christian community? A big part of my intention with religious audiences is to confirm and affirm that this is a threat to authentic Christianity as much as it is a threat to a more humble — if you will — brand of patriotism.

I draw distinctions in the book between what I call sweet fruit and bitter fruit. I consider, for instance, patriotism a sweet fruit but nationalism a bitter fruit.

But for folks who identify as Christian as I do, I think it’s incumbent upon us to recognize that there are authentic expressions of the Christian faith and idolatrous or heretical expressions of the Christian faith. And we have to be vigilant that we don’t succumb to the temptations of these bitter fruits. I’m using religious language, right?

So, for instance, in the book I talk about the idea of law and order, which is a part of this tradition brought over to North America by the English colonists. And the commitment to order is a good thing. We want to live in an orderly society. But the shadow side of that — the bitter fruit that comes with it — is violence, exercised to reinforce what we perceive to be order.

You see that violence played out in our public square all the time. We live in a very, very violent society. And you see that through expressions like “stand your ground” or, you know, “man up.” These are all very powerful expressions because they speak to a mentality that is rooted in the English Protestant language and culture, which is a very powerful motivator.

The pattern of public violence that characterizes our nation is the idea that every threat is a mortal threat and must be met with force. The patriarchal idea of being willing to “man up” and exercise violence for the cause is not unique to America by any stretch, but it’s a very American way of thinking. And it has some sweet fruit, in terms of people who were willing to risk their lives for the sake of this country.

But it also helps to explain why so often young, White men exercise violence against others, because they perceive themselves somehow to be under threat or they perceive their turf to have been encroached upon by somebody who’s somewhere they “aren’t supposed to be.” And they think that they have to exercise violence to enforce those kinds of boundaries.

For those of us who profess the Christian faith or identify with Christianity, how we choose to practice our faith and express our faith is very, very important. We must be honest with ourselves, and again, to use the religious language of repentance, we must recognize our own complicity in these ills. The challenge we all face is seeking to exercise the veteran, truer parts of our faith.

Do we see this way of thinking in some parts of the church more than others? This way of thinking is most commonly identified, and rightly so, with the evangelical branches of the American Christian family tree. White evangelical Christians are just the easiest folks to identify, who are inheritors of these ways of thinking.

But many White Americans who no longer identify with Christian traditions still were shaped by this culture and have these attitudes handed down to them across generations. They still bear within them many of these habits.

Think of habits of mind and habits of heart, these ways of thinking and viewing the world. It’s not just White Christians, and certainly not just White evangelical Christians, who have these habits of mind. But they are perhaps most strongly concentrated and expressed in White conservative, evangelical Christian circles.

In some ways, this stuff is practically mainlined into the bloodstreams of participants through the preaching, symbolism, and practices of the church. I mean, some churches are almost transparently White Christian nationalists.

Do you think that other Christian churches have a responsibility to try to combat this? Yes, I think we all do, in our own way. I would describe myself as a White progressive Christian, but I recognize my complicity in a lot of these systems myself. I don’t pretend that I’m immune from all this.

I think it’s incumbent upon everyone … to recognize that these are powerful forces in our culture and that we’re all subjected to them, we’re all exposed to them, and we all are susceptible to participate in them.

So I think it’s not as easy as good guys and bad guys. It’s much more about ways of thinking that are very, very American. And all of us who are American are susceptible to some more than others.

What do you hope to achieve in Santa Barbara? My hope is to engage people in conversation because I think understanding these roots can help us be more self-aware — help us participate in public life more productively.

I reflected in one of the chapters that I was raised in La Jolla, a privileged, White liberal enclave within San Diego. And it’s that way because of long patterns of racial segregation in San Diego, that are characteristic, again, of American life: the ways that our public life was shaped, the ways that freeways were built, the ways that communities were redlined and segregated. I enjoyed a life of privileged upbringing, in part because of those forces.

I also was raised in a community that was overwhelmingly White in which White racism was very much part of the culture there. No matter what our social positioning is, we’ve all been raised in a society in which these kinds of forces have shaped our public life, and therefore we’re all shaped by them.

What can audiences expect? One way I try to open conversation is to ask people to reflect more seriously on the religious influences of our national heritage, rather than pretending it’s an either-or, yes-or-no question to acknowledge.

Again, my fundamental argument is that the religious influences in our national heritage are very, very powerful. But they cut both ways. They are the source of much that is good about our nation and much that is bad about our nation.

And if we try to wash the religious influences out of our national heritage, we’re failing to understand how American culture works.

All the numbers of church-going are down and younger generations are less and less religious, all those things are true. But that doesn’t mean that we’re not in a nation that was influenced by religion. Quite the contrary, we’re in a nation that was powerfully shaped by religious forces and influences.

But then, to pretend that those religious influences and forces were only good and that this was a divinely sanctioned nation, that’s equally wrong.

And we have to understand our shared national inheritance has much to commend and much to lament. And I’m thinking there, for instance, of White racism, the conquest of native lands, practices of slavery, and racial segregation and continued racial discrimination, et cetera, et cetera, those are all things that are also powerfully fueled by this religious inheritance.

Is our nation’s religious heritage something that we should just wish away? No. Is it something that we should glorify and pretend to exonerate at every turn? Also no.

That’s why I’m trying to invite people to consider these things more soberly, and with a little bit more complexity, instead of pretending everything can be answered with simple yes or no questions.

Unfortunately, the event on 2/25 has been cancelled due to illness.

Premier Events

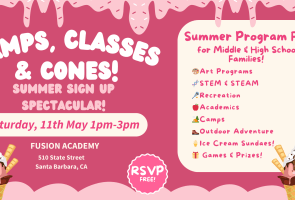

Sat, May 11

1:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Camps, Classes, and Cones! Summer Program Fair

Wed, May 08

7:30 PM

Goleta

Susan Magsamen and Ivy Ross

Thu, May 09

11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Friendship Center’s Mother’s Day Celebration

Thu, May 09

7:00 PM

Goleta

Dos Pueblos High School Presents: “Anything Goes”

Thu, May 09

7:00 PM

SANTA BARBARA

San Marcos High School Theater Presents, “Singin’ in the Rain”

Fri, May 10

10:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Covenant Living at the Samarkand Spring Art Show

Fri, May 10

12:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Mother’s Day Weekend at Art & Soul

Fri, May 10

6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Crepe Paper Flowers Workshop

Fri, May 10

7:00 PM

SANTA BARBARA

San Marcos High School Theater Presents, “Singin’ in the Rain”

Fri, May 10

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Nic & Joe Play Roy

Sat, May 11

11:00 AM

Solvang

Moms 4 Mutts! Humane Society Fundraiser

Sat, May 11 1:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Camps, Classes, and Cones! Summer Program Fair

Wed, May 08 7:30 PM

Goleta

Susan Magsamen and Ivy Ross

Thu, May 09 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Friendship Center’s Mother’s Day Celebration

Thu, May 09 7:00 PM

Goleta

Dos Pueblos High School Presents: “Anything Goes”

Thu, May 09 7:00 PM

SANTA BARBARA

San Marcos High School Theater Presents, “Singin’ in the Rain”

Fri, May 10 10:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Covenant Living at the Samarkand Spring Art Show

Fri, May 10 12:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Mother’s Day Weekend at Art & Soul

Fri, May 10 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Crepe Paper Flowers Workshop

Fri, May 10 7:00 PM

SANTA BARBARA

San Marcos High School Theater Presents, “Singin’ in the Rain”

Fri, May 10 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Nic & Joe Play Roy

Sat, May 11 11:00 AM

Solvang

You must be logged in to post a comment.