Santa Barbara Junior High School Principal Daniel Dupont remembers when the numbers began to drop. But he has also seen them begin to creep back up. “I am exceedingly proud that enrollment has continued to grow while I have been principal,” he told the Independent. “As of this morning, we are slated to have nearly 570 students next year; that’s great growth.”

Dupont credits proactive outreach to feeder elementary schools and what he calls the “Condor Advantage”: strong teaching staff, unique learning support periods, and a close partnership with Santa Barbara High School.

Despite these actions, the light at the end of the tunnel is not as bright as it seems. Context: Back in 2017, Santa Barbara Junior High had 759 students. This year, it has 502. The coming gain is hopeful, but still far from recovery.

In most California districts, enrollment decline means a direct hit to budgets because schools receive funding based on average daily attendance. But Santa Barbara Unified School District (SBUSD) is community-funded, meaning the majority of its revenue comes from local property taxes rather than per-student state funding. In other words, the district isn’t in immediate financial peril from shrinking numbers. The significance is different — it’s about shifting demographics, uneven enrollment, and campus-level imbalances.

SBUSD’s student population has dropped by more than 2,000 students in the past 10 years, shrinking from 15,593 in 2015 to 13,336 in 2025, according to California Department of Education data. At the same time, the share of socioeconomically disadvantaged students has risen from 52 percent to 61 percent. Behind both striking statistics are a number of complicated drivers, including birth rates and movement out of and within the district.

The contraction of an enrollment dip and a demographic shift is complex. It is not because more low-income families are arriving, but because middle- and upper-income families are more likely to leave. The result is a district that is both smaller and serving a student body with greater needs.

This can be seen at S.B. Junior High. In 2017, its student body was 30 percent white and 63.6 percent Latino. By 2023, it was 19 percent white and 74.5 percent Latino. For the incoming 2025 class: 12 percent white, 83 percent Latino. According to Dr. Lanny Ebenstein, a local economist, former S.B. school boardmember, and current UCSB professor, this shift is partly about transfers — often from higher-income families — to La Colina Junior High.

La Colina’s racial and ethnic makeup has been relatively stable in recent years, according to Principal Jennifer Foster. In 2024-25, the school was 39.9 percent Latino and 50.6 percent white, compared to district averages of 59.6 percent Latino and 31.2 percent white. Foster said La Colina receives many transfer requests each year. It appears test scores and perceived higher academic performance are the draw.

La Cumbre Junior High, a mere 3.5 miles away from La Colina, has held steady in size — around 450 students — but its percentage of socioeconomically disadvantaged students has grown from 85.9 percent in 2017 to more than 91 percent in 2024.

External factors are also driving declines. “It’s a super multifaceted problem. Declining enrollment is a trend that has been predicted for many years, just based on declining birth rates,” said Dr. Heather Hough, Senior Policy and Research Fellow at PACE (Policy Analysis for California Education), a Stanford-based research center focused on statewide education trends, equity, and funding. “It really accelerated during the pandemic. Another driver of declining enrollment besides birth rates is relocation out of high-cost areas. We saw a lot of migration out of those high-cost areas into lower-cost areas, some of that in the Central Valley, but also out of state.”

Of the 388 students who withdrew from SBUSD last year, 55 transferred out of California. Hough and Ebenstein both note Texas is a top destination, luring families with a lower cost of living. While private schools like Laguna Blanca have grown from 355 to 450 students since 2020, only 37 of those 388 departing SBUSD students enrolled in local private schools.

“The high cost of housing affects families across the socioeconomic spectrum,” said Ebenstein. “Even in Montecito, the price of housing has gone up so high that higher-income families cannot afford to stay.” As for the remaining 333 students who left SBUSD this past year, 55 percent went to another public school in the state, 9.5 percent to private schools, 9.5 percent out of the country, and the remaining 11.3 percent is unknown.

Back to what is happening within the S.B. schools system, at the high school level, the picture is mixed. Dos Pueblos High School has grown slightly (from 2,057 to 2,075 students since 2017) while seeing its socioeconomically disadvantaged student population rise from 35 percent to 64.5 percent.

Santa Barbara High School has dropped slightly in enrollment (from 2,112 to 2,046) while its share of socioeconomically disadvantaged students climbed from 48 percent to 61.9 percent.

San Marcos High School saw a similar trend — its student population slipping from 2,192 to 1,943, and now serving 58.8 percent socioeconomically disadvantaged students.

On state assessments, 68 percent of Dos Pueblos students met or exceeded standards in English language arts/literacy, compared to 37 percent at Santa Barbara High and 50 percent at San Marcos.

The disparities are even sharper at the junior high level. On 2024 state tests, 68 percent of La Colina students met or exceeded English language arts standards, compared to 33 percent at S.B. Junior High.

One less-discussed factor is transitional kindergarten (TK). “TK enrollment is now about 40 percent of kindergarten enrollment,” said Ebenstein. “It effectively added a half-grade to the system. Since TK didn’t exist in 2004 or even in the early 2010s, it camouflages the extent of decline in K–12.” In other words, overall headcount looks less steeply reduced because TK adds students who wouldn’t have been counted a decade ago.

Overall, he said, the district has experienced a steady decline: “The S.B. school district has gone down every year for the past 10 years. Sometimes 100 students, sometimes 300. It’s a long-term trend driven by birth data, immigration/emigration, and housing.”

So, what can be done? “Districts need to reevaluate whether their facilities match their programs,” Ebenstein said. “Reorganization and consolidation may need to be on the table.”

While parents might think that lower enrollment at their school would lead to smaller class sizes and better student-teacher ratios, that’s not how it actually plays out. “Declining enrollment does not directly impact class size,” said Ed Zuchelli, the school district’s chief of communications. “Rather, we allocate fewer teachers if a school has lower enrollment.”

Superintendent Hilda Maldonado echoed the sentiment: “With fewer students, we will need lower staffing, management, teachers, and support staff,” she said.

Despite these structural challenges, the district continues to perform well in key metrics. It has maintained a 92.4 percent graduation rate, above the state average of 86.7 percent. And 60.4 percent of SBUSD students are considered college and career ready, well above the state’s 45 percent.

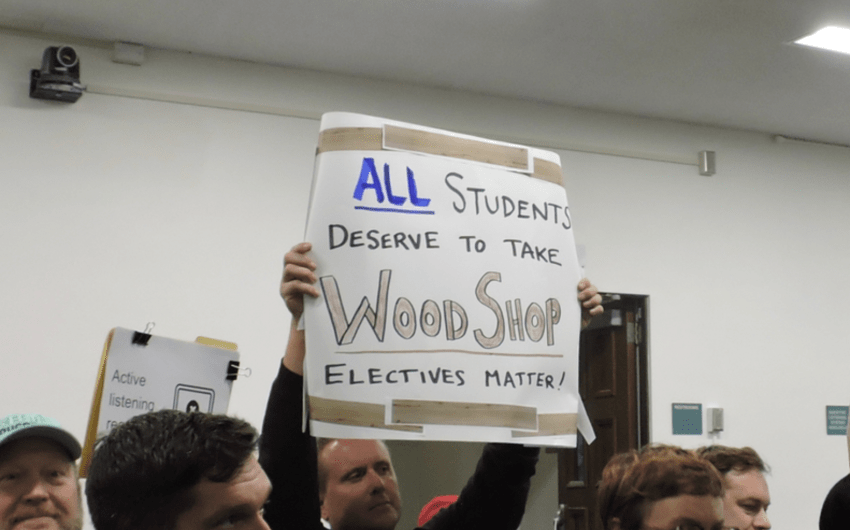

Programs at S.B. Junior High are pushing back. The school has preserved its Learning Support period and is piloting a districtwide math initiative called “A Small Test of Change,” designed to test interventions tailored to each campus. New academic pathways — including a revamped Health Careers Academy at San Marcos and dual enrollment with the community college — are designed to keep students engaged and in the district.

“Until we can have a more affordable city to live in, we may continue to see families moving out of the area, and only those who can afford the high cost will be able to stay,” Maldonado said. “Our students need job opportunities and internships in the city, county, and local businesses so that they can graduate prepared for the workforce.”

Premier Events

Fri, Mar 06

2:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Music & Meditation SB – Concert March 6, 2026

Sat, Mar 07

9:00 AM

Carpinteria

El Carro Park Cannabis Career Fair – Carpinteria

Sun, Mar 08

6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

6th Eco Hero Award Brock Dolman & Kate Lundquist

Fri, Mar 06

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

An Evening with Steep Canyon Rangers

Fri, Mar 06

8:00 PM

Santa Ynez

Funk Band Kool & The Gang at Chumash

Mon, Mar 09

6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Science Pub: Cyborg Jellies Exploring Our Oceans

Sat, Mar 28

All day

Santa Barbara

Coffee Culture Fest

Fri, Mar 06 2:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Music & Meditation SB – Concert March 6, 2026

Sat, Mar 07 9:00 AM

Carpinteria

El Carro Park Cannabis Career Fair – Carpinteria

Sun, Mar 08 6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

6th Eco Hero Award Brock Dolman & Kate Lundquist

Fri, Mar 06 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

An Evening with Steep Canyon Rangers

Fri, Mar 06 8:00 PM

Santa Ynez

Funk Band Kool & The Gang at Chumash

Mon, Mar 09 6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Science Pub: Cyborg Jellies Exploring Our Oceans

Sat, Mar 28 All day

Santa Barbara

You must be logged in to post a comment.