Santa Barbara officials unveiled a new climate adaptation plan Tuesday that outlines some significant infrastructure changes to safeguard the city’s wastewater systems from rising sea levels and intensifying storms — changes that could cost up to $130 million over the next two decades.

The Wastewater and Water Systems Climate Adaptation Plan, publicly released December 9, stems from a broader citywide resilience program launched in 2021. The plan focuses heavily on the city’s vulnerable infrastructure — including the El Estero Water Resource Center, which sits just south of Highway 101 in a historically low-lying estuary near the waterfront.

While the El Estero Water Resource Center is often pictured as vulnerable to sea-level rise, its most immediate threat isn’t from future tides, but from the influx of water that comes from extreme storm events. The facility was originally constructed on slightly elevated ground within a historically low-lying estuary, which now acts as a sort of island. That gives it some protection — for now — from direct ocean flooding and groundwater inundation.

“We’re not trying to make a decision right now to move El Estero,” said Joshua Haggmark, Santa Barbara’s Water Resources Director. “But we are preparing for the fact that, toward the end of the century, we may not be able to access the site — and we definitely don’t want to wait until it’s flooded to figure that out.”

El Estero treats approximately 6 million gallons of wastewater per day, serving as a linchpin in the city’s public health and environmental protections. But during extreme weather — such as the record-setting rainstorm this November — the facility was pushed to capacity, processing 30 million gallons in a single day.

At issue is not just rainfall, but infiltration. Santa Barbara’s sewer system is gravity-fed, which means water — including rain or seawater — can seep in through failing pipes, manholes, or aging lateral connections.

Currently, the plant faces seasonal challenges when heavy rainfall overwhelms the system. But the city is looking ahead: sea-level rise, more intense bursts of rainfall, and storm surge are all expected to accelerate in coming decades.

“The death knell is when we get seawater coming in,” Haggmark said. “The salt will kill the bacteria we rely on to treat our waste.”

The plan lays out short-, mid-, and long-term projections based on current climate science:

- Now–2050: Expecting up to 0.8 feet of sea-level rise, with more intense rainfall events.

- 2050–2075: Planning for up to 2.5 feet of rise and increasing flood frequency.

- By 2100: Worst-case projections show 4.9 feet of sea-level rise, which would place the El Estero facility and much of the Waterfront at risk of routine inundation.

“Extreme rain events are so much more likely now,” said Melissa Hetrick, the city’s Adaptation and Resilience Manager. “We’re seeing more moisture held in the upper atmosphere, which means bigger bursts of rain, even when total annual rainfall doesn’t change much.”

To combat that, the city is exploring pressurizing the sewer system in low-lying neighborhoods, sealing manholes, lining aging mains, and increasing system storage. Hetrick cited New Orleans as examples of successful low-pressure systems.

“We’re trying to be proactive,” she said. “If we start early, we have more options.”

The plan’s most eye-catching line item is the possibility of relocating El Estero, a project that could cost up to $850 million. While that decision isn’t imminent, city staff emphasized the need to identify potential future sites now — ideally in areas not vulnerable to sea-level rise.

Among the options? The city’s 110-acre municipal golf course.

In the meantime, the city is pursuing “protect in place” strategies: building floodwalls, elevating key electrical infrastructure, and improving emergency access roads over the next 25 years. These upgrades are necessary, officials say, to avoid catastrophic overflows and protect critical systems during high-impact events.

“When we max out capacity, it leads to overflow,” Haggmark said. “And that’s the big fear.”

The adaptation effort is currently being funded by state and local grants, with support from agencies including the California Coastal Commission and the State Coastal Conservancy. To date, the city has secured roughly $5 million and is applying for more.

The plan is now open for public comment for 60 days, with presentations scheduled for the Water Commission on December 18, Planning Commission in early 2026, and City Council in April for final approval.

In the next 20 years, the city estimates it will need:

- $2–3 million for studies and design

- $50–130 million for infrastructure upgrades

- Additional staffing and technical capacity to carry the work forward

Despite the daunting projections and dollar signs, both Hetrick and Haggmark underscored the importance of starting now — and taking it step by step.

“We’re looking at this day by day,” Haggmark said, “but with the long term in mind.”

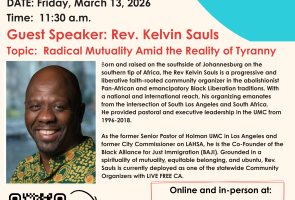

Premier Events

Thu, Feb 26

11:00 AM

Montecito

La Casa de Maria – Lunch and Learn

Sun, Mar 08

6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

6th Eco Hero Award Brock Dolman & Kate Lundquist

Mon, Feb 23

6:30 PM

Santa Ynez

FREE Concordia Handbells in Concert

Mon, Feb 23

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SBCC Big Band Jazz at SOhO

Tue, Feb 24

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Banff Mountain Film Festival World Tour: 2 Nights!

Wed, Feb 25

4:00 PM

SANTA BARBARA

Career Exploration Fair: For Teens & Young Adults

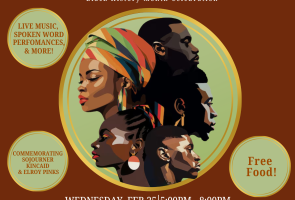

Wed, Feb 25

5:00 PM

Isla Vista

Forward Ever Backward Never

Wed, Feb 25

6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Creative Exploration

Wed, Feb 25

8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Salvidoria, Orangepit!, & Magnetize at SOhO

Thu, Feb 26

1:00 PM

SANTA BARBARA

Shocking History of Electricity in Santa Barbara

Thu, Feb 26

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Anniversary Screening – Connectivity: “Chulas Fronteras”

Thu, Feb 26

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Beautiful Borders: Texas-Mexico Crossings in Film

Thu, Feb 26 11:00 AM

Montecito

La Casa de Maria – Lunch and Learn

Sun, Mar 08 6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

6th Eco Hero Award Brock Dolman & Kate Lundquist

Mon, Feb 23 6:30 PM

Santa Ynez

FREE Concordia Handbells in Concert

Mon, Feb 23 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SBCC Big Band Jazz at SOhO

Tue, Feb 24 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Banff Mountain Film Festival World Tour: 2 Nights!

Wed, Feb 25 4:00 PM

SANTA BARBARA

Career Exploration Fair: For Teens & Young Adults

Wed, Feb 25 5:00 PM

Isla Vista

Forward Ever Backward Never

Wed, Feb 25 6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Creative Exploration

Wed, Feb 25 8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Salvidoria, Orangepit!, & Magnetize at SOhO

Thu, Feb 26 1:00 PM

SANTA BARBARA

Shocking History of Electricity in Santa Barbara

Thu, Feb 26 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Anniversary Screening – Connectivity: “Chulas Fronteras”

Thu, Feb 26 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara