By January 9, eight days after California’s updated plastic bag ban went into effect, the change was obvious in grocery stores across Santa Barbara.

At Sprouts, Ralphs, and Pavilions, checkout lines moved without the usage of familiar bagging of thick plastic “reusable” bags — the kind the state now says were rarely reused at all. Some shoppers arrived prepared, unfolding canvas totes or nylon sacks. Others skipped bags entirely, loading groceries directly into their carts and then into their cars. And at least one shopper arrived with a homemade bagging attachment fashioned from an old toolbox, clipped onto his cart so he could pack groceries himself.

California’s revised carryout bag law, which took effect January 1, eliminates the exemption that allowed thicker plastic bags to be sold as reusable. State officials say the change closes a loophole that undermined the original intent of the law.

At Sprouts, where plastic bags had already been phased down, an employee said the store simply allowed its remaining supply to run out. “We ran out exactly on New Year’s Eve, and by New Year’s Day, we were in compliance.”

That approach aligns with how grocery stores across California prepared for the change, according to Nate Rose, vice president of communications and public affairs for the California Grocers Association.

“In theory, groceries have been working to go through those plastic bags and sell them to customers as they were allowed to until January 1 of this year,” Rose said. “Grocers order those bags by the shipping container, so the goal was to move those through the system in anticipation of making the full switch to paper bags or reusable canvas types.”

Rose said grocery operators supported the updated law and worked with state lawmakers as it took shape. “We supported the legislation,” he said. “We worked closely with Assemblymember Rebecca Bauer-Kahan alongside Senators Ben Allen and Catherine Blakespear to arrive at a policy that worked for environmental advocates, customers, and grocery store operators.”

Many stores now sell reusable felt bags — at Sprouts, they cost 25 cents — and also provide compostable produce bags. At grocery stores like Trader Joe’s and Whole Foods, they had already been using paper bags for years. According to guidance from CalRecycle, retailers are allowed to sell paper bags, often for a fee, and reusable bags made from cloth or other durable materials. Plastic carryout bags, regardless of thickness, are no longer permitted.

Among shoppers, reactions ranged from indifference to ingenuity. Several shoppers waiting in checkout lines said they supported the change, even if it meant occasional inconvenience. Some described forgetting their bags and opting to carry groceries by hand rather than purchase another reusable one.

At Ralphs, one shopper drew attention for using a self-built bagging station attached to his cart, designed to hold plastic bags he brought from home. Asked about it, the shopper said he resented being told what to do by legislators.

Other customers nearby described the scene as ironic rather than defiant. One shopper said the man was “doing exactly what the legislation was meant to do: eliminating new plastic bag usage and urging people to bring their own bags.”

Rose said that while the law reflects the same goals as California’s original plastic bag ban, changing habits can take time — particularly after disruptions during the pandemic where there were fears that bringing your own bag may aid the spread of COVID-19.

“The spirit of the law is very much the same as what we did 10 years ago — to incentivize people to bring their bags from home and to reuse them,” he said. “But policies are living things, and you do need to revisit them from time to time to see if they’re still having the impact they were designed to have.”

Rose said there was growing concern that the thicker plastic bags were no longer being reused as intended. “There was a sense that even though the bags were reusable, people were using them in a disposable fashion,” he said. “Some of that may go back to the pandemic, when shoppers weren’t allowed to bring reusable bags into stores for a period of time. That may have broken the habit.”

Environmental groups say the amended law reflects years of data showing that thicker plastic bags did not meaningfully reduce waste. A 2025 peer-reviewed study found that plastic bag bans lead to a 25-47 percent reduction in plastic bags in the environment where implemented, according to Ocean Conservancy.

“By removing the exception for thicker plastic bags, California will finally live up to its intended goal of eliminating plastic grocery bags,” said Dr. Anja Brandon, the organization’s director of plastics policy, in a statement released January 1. “Plastic grocery bags are not only one of the most common plastics polluting our beaches, but also one of the top five deadliest forms of plastic pollution to marine life.”

Ocean Conservancy’s research has shown that plastic bags are frequently mistaken for jellyfish by sea turtles and other marine animals, leading to fatal ingestion. The group estimates that Americans use roughly 100 billion plastic grocery bags each year, often for just minutes before disposal.

The timing of the new ban comes as reusable bags have taken on a cultural life of their own, particularly at Trader Joe’s. The grocer has long relied on paper bags at checkout while selling reusable canvas totes, some of which have become viral collectibles. Limited-edition releases, including mini totes and seasonal designs, have repeatedly sold out.

Rose said the transition has cost implications for smaller and independent grocers, particularly when it comes to paper bags. “Paper bags are a lot more expensive than the reusable plastic bags were,” he said. “Some smaller grocers are paying over a dollar per bag. Grocery stores operate on incredibly thin profit margins — about 1.6 percent — so if you’re selling a bag for 10 cents that costs over a dollar, you’re losing money.”

Despite the potential added cost, across California the adjustment is underway, as required by law. However it looks in practice, the result is the same: goodbye to plastic bags.

Premier Events

Fri, Mar 06

2:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Music & Meditation SB – Concert March 6, 2026

Sat, Mar 07

9:00 AM

Carpinteria

El Carro Park Cannabis Career Fair – Carpinteria

Sat, Mar 07

2:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Autobiography of a Yogi, the Legacy of Yogananda

Sun, Mar 08

6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

6th Eco Hero Award Brock Dolman & Kate Lundquist

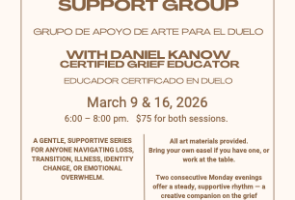

Mon, Mar 09

6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

ART 4 GRIEF Support Group

Fri, Mar 06

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

An Evening with Steep Canyon Rangers

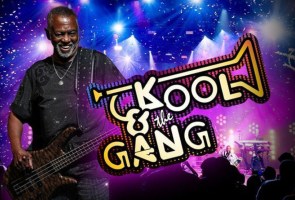

Fri, Mar 06

8:00 PM

Santa Ynez

Funk Band Kool & The Gang at Chumash

Sat, Mar 07

12:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Spring 2026 Healing Arts Faire

Sat, Mar 07

7:00 PM

Carpinteria

The Magic’s In the Music

Sat, Mar 07

7:30 PM

Goleta

UCSB Arts & Lectures Presents Arturo Sandoval Legacy Quintet

Sat, Mar 07

7:30 PM

Goleta

Jazz Concert with Wayne Bergeron

Sun, Mar 08

10:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Fairytale Weekend at the Zoo

Sun, Mar 08

1:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SB Craftivists “Resist with Love KNOT Hate Knit-In

Sun, Mar 08

4:00 PM

Santa Barbara

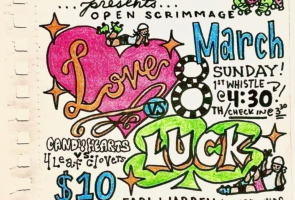

Brawlin’ Betties: Love v. Luck Scrimmage

Sun, Mar 08

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

SBAcoustic Presents Natalie Gelman & Mark Legget

Fri, Mar 06 2:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Music & Meditation SB – Concert March 6, 2026

Sat, Mar 07 9:00 AM

Carpinteria

El Carro Park Cannabis Career Fair – Carpinteria

Sat, Mar 07 2:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Autobiography of a Yogi, the Legacy of Yogananda

Sun, Mar 08 6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

6th Eco Hero Award Brock Dolman & Kate Lundquist

Mon, Mar 09 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

ART 4 GRIEF Support Group

Fri, Mar 06 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

An Evening with Steep Canyon Rangers

Fri, Mar 06 8:00 PM

Santa Ynez

Funk Band Kool & The Gang at Chumash

Sat, Mar 07 12:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Spring 2026 Healing Arts Faire

Sat, Mar 07 7:00 PM

Carpinteria

The Magic’s In the Music

Sat, Mar 07 7:30 PM

Goleta

UCSB Arts & Lectures Presents Arturo Sandoval Legacy Quintet

Sat, Mar 07 7:30 PM

Goleta

Jazz Concert with Wayne Bergeron

Sun, Mar 08 10:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Fairytale Weekend at the Zoo

Sun, Mar 08 1:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SB Craftivists “Resist with Love KNOT Hate Knit-In

Sun, Mar 08 4:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Brawlin’ Betties: Love v. Luck Scrimmage

Sun, Mar 08 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

You must be logged in to post a comment.