Can He Kick It?

Dos Pueblos High Football Star Josh Johnson, Now 38, Placekicks His Way Toward the NFL

“Maybe what I’m doing can be an inspiration to somebody.”

It’s a Wednesday morning, and Josh Johnson is practically all alone on one half of the Santa Barbara City College football field. As an ultimate Frisbee class congregates on the opposite side of the field and joggers circle the track, Johnson’s only companions are four National Football League-legit footballs — his only goal, to kick them through the yellow uprights.

Though the seaside air proves particularly gusty this morning and the goalposts stand a bit tilted from the winter’s stormy weather, Johnson easily gets the job done. He is automatic from 20 and 30 yards out — not even needing to step back, but simply pushing the balls through their targets with just a giant sweep of his right leg. Moving back to 40 yards, he goes through a more typical two-step-drop placekicking routine and hits 13 out of 21. That may be only a couple kicks above 50 percent, but Johnson’s goal this morning isn’t so much accuracy or distance — it’s form. “All I want to see right now is that end-over-end,” said Johnson, referring to the desired motion of the ball.

The exercise is not some personal contest for Johnson, nor is he out for just another morning workout. In fact, Johnson’s goal is much loftier. He intends to kick for a team in the National Football League before this year is up, as the oldest rookie ever to join the league. Call him crazy, but even at 38 years old, the 5’11”, 205-pound Johnson — who hasn’t kicked competitively since his days at Dos Pueblos High School — doesn’t give the impression that he is anything but serious. For five months, he has set most everything in his life aside and zoned in on this dream, one that he put on hold nearly 20 years ago when he gave up kicking after freshman year in college.

While there’s no doubt Johnson has a powerful leg and was a memorably outstanding kicker in high school, there remains a very thin chance that he — or anyone with the consistent ability to pummel a pigskin through the uprights — will ever play at a professional level. Of the 10,000 high school football players in America every year, only about eight eventually make it to the NFL — and they tend to be the best and brightest stars who continued to excel at big-name colleges and enter the league in their primes, not after taking 20 years off. Even then, prospective placekickers still are worse off, since most of the NFL’s 32 teams employ, at most, two kickers. That leaves 64 spots total, the overwhelming majority of which are already filled. As a former NFL kicking coach said, Johnson’s hardly got a chance.

But that’s all fine and dandy for Johnson. He’s well aware of the challenges, and his quest goes beyond kicking balls through posts. This adventure is about inspiration and realizing your full potential, and about following dreams, no matter the odds. “I don’t have the desire to play football just to play football,” said Johnson. “For me, it’s going to the top, all or nothing — NFL or bust.”

Kickoff

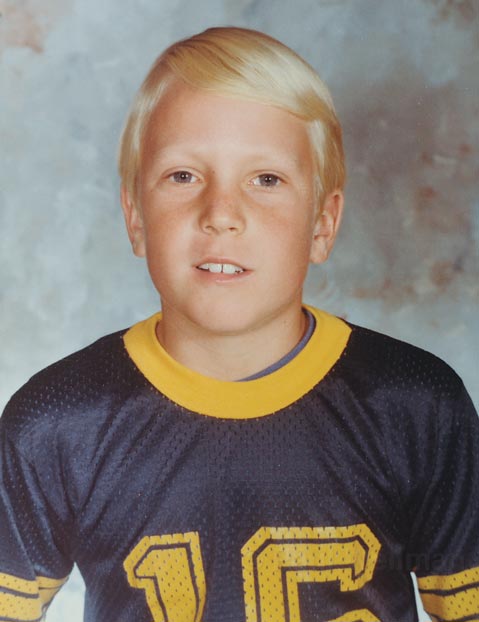

Born at Goleta Valley Hospital in October 1971 to a family with strong Santa Barbara roots — his family once owned plenty of land on the Mesa — Josh Johnson has lived in the Santa Barbara area most of his life, attending Kellogg Elementary and Goleta Valley Junior High. He started soccer at a young age and remembers, even then, having an abnormally strong leg. “As a kid, I scored a goal from half-field,” he recalled. “It bounced in front of the goalie, over, and in.” He also excelled at tennis, having grown up with a public court practically in his backyard, and was known to shoot hoops at the Boys & Girls Club. But it wasn’t until high school that Johnson found football because, according to a 1989 article in the Santa Barbara News-Press, his dad wouldn’t let him play.

On the gridiron as a Dos Pueblos High Charger, Johnson and his talents as an all-around athlete began to blossom, and he led the team as a quarterback all through his DP days. He discovered his knack for kicking toward the end of his junior year and then shined in the position as a senior. That season of 1989, according to archived News-Press statistics, Johnson kicked at least six field goals, skewering the uprights from lengths including 52, 47, 46, and 45 yards — standout distances for any kicker, let alone a high schooler. There’s no record of him missing a single one that year. “He certainly was an outstanding high school kicker,” said his former coach Jeff Hesselmeyer, who now coaches at San Marcos. “We were never afraid to try it. He was a good weapon to have.”

One day prior to practice, while warming up with field goals as usual, Johnson nailed a 50-yarder. Then, with teammates watching, he backed up to the 50-yard line and teed up the ball for what would be the equivalent of a 60-yard kick (because the end zone is 10 yards deep). Knowing that the longstanding NFL record was just steps further at 63 yards, everyone there that day still remembers Johnson lining up the kick, making solid contact, and then watching the ball bounce off the crossbar and through the uprights. “He’d always just size it up and kick the crap out of it,” said his former holder, Eric Eremia, who also recalls Johnson’s punting prowess, including one 67-yarder. “In a lot of ways, his kicking and punting kept us in games.”

Though Johnson received walk-on offers from USC (he couldn’t afford the yearly tuition) and several Division I schools, he opted for San Diego State, which is also where his friend and DP’s star running back Marcus Preciado decided to go. Because the Aztecs already had a scholarship kicker named Andy Trakas on the roster, Johnson was redshirted, so he wouldn’t see any game time all year. Meanwhile, the coaches made him train as a punter rather than placekicker, a move Johnson “never understood,” especially when he thought of himself as the better kicker.

The final straw came when the Aztecs traveled to Florida to play the vaunted University of Miami Hurricanes on December 1, 1990. The game was tight, despite the vast difference in records and reputations. Trakas missed three field goals in the fourth quarter, and the Aztecs ended up losing by two, 30-28. “I’ll never forget that,” Johnson said. “I could’ve helped win against Miami at Jack Murphy Stadium.”

When the season ended, Johnson began feeling burned out by football, largely because he believed that he’d never get a chance to kick. He wanted to move on and did so by transferring to Humboldt State, where he majored in sociology and pursued another passion: music. The band he formed ended up only playing in front of parties and some clubs, and after graduation, Johnson hopped from odd job to odd job as he traveled from country to country. In between writing music and forming bands, Johnson also sold cars and worked for a veterinarian.

Game Time

When his dad died in 2002, Josh Johnson went on a soul-searching mission and started taking life more seriously. He wound up in Phoenix, Arizona, where he attended the Motorcycle Mechanics Institute. “I’d always been a motorcycle guy,” said Johnson, who worked at a Harley shop in Nevada before being offered a job at the Santa Barbara Harley store, where he worked until 2006 as a finance manager.

Around that time, Johnson began thinking about his father, who died at age 59 from skin cancer that wasn’t spotted until its late stages. He remembered the impact his father, an elementary school principal, had on so many people and wondered whether he should use his own athletic talents while he still had time. “What if I only have 20 more years?” he remembered thinking. Serendipitously, the “athletic thing started coming back,” said Johnson, who started feeling guilty for not pursuing that side of his life. “It’s now or never,” he told himself, and he decided in December 2009 to see what he had. He kicked a few times and saw he still had a leg on him. “Alright, it’s still there,” Johnson told himself. “I got a long way to go, but it’s still there.”

Johnson’s high school teammates have always known it’s there, and few doubt that he had the leg to kick professionally. He was the consummate athlete, one said, talented and gifted beyond anyone he had ever met. They just wonder what took him so long. “It’s really something he should’ve been doing all along,” said Eremia. “When you see someone have that talent, you wonder why you would stop.”

The question for Johnson is whether his stopping will ultimately affect his chances of starting in football games ever again, and for an NFL team, no less. A land of 350-pound beasts who sprint like the wind, make more money than corporate executives, and get watched by millions of fans every fall weekend, the NFL is no joke — pressure is intense, and opportunities are few and fleeting. And while the kicker may only spend mere seconds on the field even in a game when his team needs him the most, the final score often comes down to the stroke of his leg.

Take the playoff game last fall, when San Diego Charger kicker Nate Kaeding stepped onto the field as one of the most successful kickers in NFL history, having put 87.7 percent of his kicks through the uprights. With less than five minutes left, his team was down by 10, and a field goal would put them within one possession and an opportunity to win the game. Despite an hour-long battle of two 11-player teams, everyone was relying on Kaeding, who was usually a sure-thing but had already missed two field goals earlier in the game. He missed again, and the Chargers lost by three.

While established pros like Kaeding can survive even such a serious snafu, the NFL is notoriously harsh on lesser kickers. Just last season, when Dallas Cowboys kicker Nick Folk missed seven of his last 11 attempts, he was fired. His replacement was Shaun Suisham, a kicker who’d lost his job with the Washington Redskins only two weeks earlier when he missed a game-winning, 23-yard field goal. A few weeks later, Suisham missed two more field goals, and the Cowboys fell in the playoffs. Due to that, Suisham’s contract was not renewed by the Cowboys, and he’s now a free agent, angling for another kicking job much like Johnson is.

It’s exactly those sorts of high-profile struggles that caught Johnson’s attention. For eight straight years in the NFL, the percentage of successful field goals crept higher. But then last season, success dropped by 3 percent. Johnson’s former teammates have also noticed a slide in NFL kicking. “Every time I see a field-goal kicker miss a kick, I think, Josh Johnson could’ve made that kick,” said Eremia, which is no small statement, since the two hadn’t spoken in years until recently. Former teammate David Zuniga agreed. “Whenever I see someone line up for a long field goal,” he explained, “I remember that long field goal in practice.” Johnson’s kicking, in fact, is one of two things that Zuniga said he’ll never forget from his high school days. (The other is watching Oxnard’s Rio Mesa High School standout Dimitri Young, now a pro baseball star, hit a homerun out of Dos Pueblos’ park.) “When we were in the huddle for extra points, he would joke about which cheerleader he should hit,” Zuniga laughed. “He literally had that sort of talent.”

Of course there’s no drastic dearth of talent in the NFL, either — despite 2009’s 3-percent drop, kickers still made 81 percent of field goal attempts. Plus, there are plenty of able-footed kickers in the Canadian Football League, on European teams, and in the Arena Football League. In other words, there’s a lot of competition for one, maybe two, open kicking spots in the NFL.

One expert put a sobering perspective on Johnson’s chances. “I’d say he has no chance,” assessed Gary Zauner, who coached special teams in the NFL for 13 years and continues to train kickers at all levels. “There are too many good kickers that don’t have a job.” The chasing-the-dream story is nothing new to Zauner, who appreciates such undertakings but doesn’t look at them too seriously. The only time he personally would work with a man of Johnson’s age, explained Zauner, is if they had years of NFL experience and were, say, retired but wanted to make a comeback.

Zauner admits that there are some teams with two kickers, typically in which the younger player does the kickoffs and the older, more experienced one focuses on field goals. Even that, though, probably doesn’t help Johnson’s chances. “If a guy is a great kicker, he can still have a say in wins and losses, despite his age,” Zauner explained. “But you gotta be around a long time to deserve that opportunity.”

Ask Johnson what his chances are, and he sees things in a different light. “The only way I can answer that is 100 percent,” he said. “Honestly, if I didn’t think I could make the NFL, I wouldn’t even try.”

And it seems that fate — combined with Johnson’s hard work — is putting him in a position to be seen and perhaps beat the odds. He’s been able to attract a decent amount of media attention from throughout Southern California, including one online interview that caught the eye of famed kicker Morten Andersen, one of the best NFL field-goalers ever. If Andersen — who’s since contacted the DP grad — thinks Johnson has what it takes, it might just take one phone call to get an audience with an eager general manager. “Little things like that keep falling into place,” said Johnson.

Then there’s the possibility of an NFL owner wanting to drum up publicity for his football team. “Stranger things have happened,” said Johnson, who’s been researching which teams need kickers next season. “All it’s going to take is a general manager thinking outside the box.”

Sudden Death

Johnson’s first official big chance comes on May 29 at a regional combine in Los Angeles, where NFL hopefuls come from all over the West Coast to try out. Unlike the other positions, kickers aren’t graded on 40-yard dash speed, weightlifting, or agility, but strictly on the distance, hang time, and accuracy of their kicks.

Specifically, the kickoffs are graded 50 percent on distance and 50 percent on hang time — to get a “pro prospect” grade, the ball must hang at least 3.85 seconds and sail more than 62 yards. But if Johnson really wants a chance, he’d better hang the ball in the air for 4.05 seconds and fly it 67 yards. Then comes the field goal round, in which kickers must attempt eight kicks from 30-55 yards and then another two from 45 and two from 50 yards. The final grade is weighted much more heavily toward field goal kicking, with kickoff ability accounting for only 30 percent of a kicker’s tally. Should a kicker achieve a promising score, he’ll qualify for the national combine in Indianapolis on June 18 and 19, where he’ll be tested again, but this time under the watchful eyes of professional scouts and coaches.

Until the May try-out, Johnson is surrounding himself with a team of coaches — known without irony as “NFL or Bust” — that is designed to get him in shape both physically and mentally. He works out four days a week with a personal trainer, kicks every other day, and has employed a chiropractor, massage therapist, and specialist focusing on mental strength. His dedication has even translated to living out of his RV in order to save the money that he’s paying to the supporting squad. Said Johnson, “You gotta jump in with both feet.”

Johnson’s friends from high school and since say his drive has never been stronger, and that though they know he’s a restless spirit, they believe he’s setting an example for people to follow their dreams, no matter the outcome. For Johnson, his late father never strays far from his mind. “He was an inspiration to tons of people,” said Johnson. “Maybe what I’m doing can be an inspiration to somebody.”

“Josh is living and breathing this every minute of the day,” explained friend Richard Girard, who’s been known to shag balls from behind the uprights. Added former teammate Zuniga, “He’s got this thing deep in his heart, and I just really hope he succeeds.”