The Kidnap Scam

One Montecito Family’s Tale of Terror

The call came at midnight as Audrey Tognotti and her mother strolled the Latin Quarter of Paris after a late supper. Audrey didn’t recognize the number, but she wasn’t surprised to get an international call while on vacation halfway around the world from her husband and kids. She picked up. The first thing she heard was a little girl screaming for help. Then a man’s voice: “We have your daughter.”

Audrey froze. She cried her daughter’s name — “Addy!” — and asked the caller what he wanted. “We have your Addy!” His voice was stern and carried a slight Spanish accent. “She was in the wrong place at the wrong time, and now we have her.” More screams pierced the background.

For the next two and a half hours, the caller kept Audrey on the line. He shouted commands. He threatened her daughter’s life. Not for one moment did Audrey doubt that her daughter was in grave danger. She told herself she must follow the kidnapper’s orders not to hang up until the ransom was paid and Addy safely returned. Not once did it cross her mind that the call was a hoax, an elaborate extortion scam carried out from Mexico by organized criminals armed with disposable cell phones and a list of numbers with 805 area codes.

Audrey’s midnight call was just one in a recent spate of virtual kidnappings, as the FBI calls them, in Santa Barbara County and other nearby regions. During the first 10 months of this year in the U.S., there were 112 kidnappings reported to the FBI, 19 of which were virtual. Not all virtual kidnappings are reported to the FBI, however, and according to the agency’s press office, “[We] believe that a significant number of virtual kidnappings are still going unreported.”

Closer to home, the Santa Barbara Police Department and Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s Office have each reported a handful this year — “Enough for us to be concerned,” said Kelly Hoover, the Sheriff’s Office’s public information officer. Law enforcement officials believe most of these attempted extortions fall flat, as targeted victims hang up at some point. Some calls, however, escalate rapidly as callers prey on all parents’ greatest fear.

But Audrey Tognotti and her husband, Mike Tognotti, knew nothing about these scams. For them, the situation quickly developed into a perfect storm of desperation and despair, peaking in intensity with Audrey in Paris, believing her daughter was gone, and Mike in Santa Barbara, wiring ransom payment to Mexico City. In the end, with all family members safe and accounted for — the incident recognized as nothing more or less than a horrible scare — the Tognottis agreed to tell their story. To talk about it publically, they said, would help them process lingering trauma, bring clarity to vague news reports, and, most importantly, get the word out that families ought to be vigilant, even with something as innocuous as an incoming phone call.

Audrey’s Angels

A few seconds after the call came in, Audrey’s mother, Suzanne Danielson, watched fear flood her daughter’s face. Audrey cried into the phone, “How much do you want? … But it’s the middle of the night, and I can’t get any money. … You have to call my husband. … Please let me talk to my daughter!” Danielson slipped into a state of expedited efficiency. “I knew I had to do something fast,” she remembered. “You don’t cry; you just get it done.”

Motioning to her mother, Audrey fished a pen from her handbag and wrote “CALL MIKE” on her arm. Danielson ran into the closest café, where she recognized the Canadian owner of the nearby Abbey Bookshop, Brian Spence. In broken French, she offered him 100 euros to use his phone for an emergency call. Spence rushed Danielson to his bookstore. On the way, he recognized a couple he knew: an American and his girlfriend, who both work at the U.S. Embassy in Paris. The couple had been out enjoying Nuit Blanche, an annual all-night art festival. When they understood the situation, they offered to help. Danielson — a dedicated follower of television’s Forensic Files and thriller novelists Ken Follett and Robert Ludlum — asked to see their IDs before launching the first surge of spontaneous teamwork.

Danielson had left her phone in the vacation flat, and like so many of us these days, she didn’t have family phone numbers committed to memory. Spence handed her a landline and fired up the shop computer so she could pull up Mike’s cell number and email. The couple with the U.S. Embassy located their contact there, a man known as Jimmy, who asked Danielson the names and possible whereabouts of family members back home in Santa Barbara. Jimmy then called Santa Barbara’s Sheriff’s Office to report the kidnapping.

Alone in the alley outside her flat, Audrey kept her line open, clinging to the only connection she had to her 10-year-old daughter. The supposed kidnapper learned she was in Paris with her mother, but Audrey lied about her mother’s whereabouts, saying she was asleep. Audrey was then ordered to go into the apartment to charge her phone. There she changed into warm, comfortable clothes for what she expected to be a long and scary night ahead.

She realized that with the banks and wire services closed in Paris, ransom payment for Addy’s return was now entirely up to Mike.

‘We Have Your Wife’

Mike Tognotti and his eldest daughter, Sofia, were in the checkout line at Ralphs downtown that Saturday afternoon when the call came in from an international number. He picked up. “We have your wife,” said the caller. Mike’s heart rate spiked, and he paced nervously as the caller barked orders. Sofia grabbed the groceries, and they went outside. For a moment, he heard a frantic plea, sounding like his wife’s voice on a speakerphone, “Mike, this is Audrey. Just cooperate, and everything will be okay.” Mike called out her name. Nothing. The caller shot back: “Go to the bank! Now!”

Mike muted the call just long enough to break down the situation to 14-year-old Sofia and to tell her to pull her younger sister, Addy, from ballet class, a few blocks away. Back on the phone, the caller yelled at Mike. “Don’t do that again! Who’s with you?” Mike said he was alone.

When Sofia returned with Addy, the three drove toward Bank of America on State Street. Mike, following instructions, updated the caller with his exact location. Addy, frightened and confused, turned to her big sister for comfort. “Sofia was stoic, calm, and poised,” Mike remembered. “She really helped her sister and me get through this.”

They arrived at the bank. It was closed. A big withdraw was out of the question. Looking back now, Mike says he was in such a state of stressed-out urgency that he didn’t find it odd that the kidnapper of his wife would settle for as much cash as he could gather from multiple ATMs. After Mike made two withdraws from B of A, the caller told him to go up State Street one block and then right on Carrillo to Union Bank. Mike felt as if the caller were watching his every step. (He knows now that the caller had likely pulled up his location on an online map, pinpointing nearby ATMs.) At Union Bank, Mike frantically cut to the front of the line, stunning a tourist couple with the terrible news of his wife’s kidnapping.

With $1,000 in hand — $900 from ATMs and another $100 pitched in by Sofia, who had been planning to buy her first puppy later that day — Mike and his daughters headed back down State Street to the Western Union inside Rite Aid. With the end now in sight, both daughters by his side, Mike had followed orders, remaining on the phone line and staying focused. He had also ignored incoming calls, including one from his mother-in-law in Paris, saying Addy had been kidnapped.

While Mike had been frantically gathering the ransom payment, Audrey had walked to a nearby church. She sat on the steps and prayed, curling up against the cold. A random person materialized from the night and gave her a seat cushion. Keeping her on the line, the caller told Audrey to tell stories about her family. She talked about get-togethers. She sang. She prayed some more. She asked if Addy was okay. The caller said that his men were playing with her — but it wasn’t the sort of playing a mother would approve of. Then she heard more screaming.

Federal Agents

Extortive phone scams have evolved over the years and have taken many forms, according to Erik Arbuthnot, an international violent crime specialist with the FBI. They began showing up more than a decade ago, when Mexican families living in the U.S. were getting calls from Mexico saying that family members there had been kidnapped or imprisoned. Another approach involved friends and family members of people vacationing in foreign resorts. In those cases, an employee at a vacation resort would sell to the scammers the phone numbers and names guests had given the hotel as emergency contacts. These days, the trend is to target wealthy area codes — Santa Barbara, Beverly Hills, West Los Angeles, and Montgomery County in Texas — and cold-call in English. “Their goal is to steal money,” Arbuthnot said. “And they’re good at creating a real level of panic.”

Instilling panic works to the caller’s advantage. For example, that screaming girl in the background could compel a parent to call out to his or her child. And just like that, the caller learns her name. Once the panic sets in, it’s easier for the caller to keep a parent on the line — by threatening to kill their child, for example — which allows time for the gathering and wiring of ransom payment.

“The FBI’s recommendation is that if you get a call like this, hang up, locate your family members, and call the police, in that order,” said Arbuthnot. His advice is part of an ongoing, multi-agency effort called Operation Hang Up, initiated by a task force that includes representatives from the IRS’s Criminal Investigation division, the U.S. Border Patrol, and Los Angeles city and county detectives, among others.

But what about following a wire transfer into Mexico and closing in on whoever is there to physically retrieve it? “My short answer to that question is that I don’t have jurisdiction in Mexico,” Arbuthnot said without elaborating. “Trying to follow a payment across an international border becomes complex.”

Try to imagine a successful arrest of a hastily arranged wire transfer to Mexico City, for example: It would have to include a law enforcement agency knowing about the wire before it was sent, or very soon thereafter, and it would require coordination with Mexican authorities. If that international, multi-agency effort was capable of achieving the speed and accuracy necessary to intercept a money-wire recipient, how likely is it that such mobilization even makes sense when there are real kidnappings and other violent crimes that need attention?

“Due to the fact that the scheme is primarily perpetrated remotely and via burner phones, it is difficult to bring charges and/or prosecute a case fully,” said Lourdes Arocho with the FBI’s press office, via email. “[As of September 2016], the FBI does not have an example of a virtual kidnapping case that has been prosecuted and adjudicated.”

Officer Tonello, SBPD

After wiring the $1,000 to Mexico City, Mike remained on the line. He needed to hear that Audrey was going to be okay. The caller told him to rip up the Western Union receipt close to the phone so he could hear the evidence being destroyed. Mike simply crumpled it loudly; he wanted to preserve it for a potential investigation and maybe even get his $1,000 back.

According to Sarah Meske, Western Union’s communications director, refunds are available to senders who cancel a transaction before the money’s been picked up. “Western Union is firmly committed to preventing the misuse of its service, [and] more than 20 percent of our workforce is engaged in enforcing compliance,” she added. “We continue to work closely with law enforcement across the globe, including ongoing cooperation with active police investigations in the fight against all illicit activity.”

Since 2012, according to Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) documents, Western Union has been under investigation by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which “believes that [Western Union] bears responsibility for principal amounts of what it alleges to be hundreds of millions of dollars in fraud-induced money transfers … .” Earlier this year, the FTC told Western Union it was in violation of federal law “by failing to take timely, appropriate, and effective measures to mitigate fraud in the processing of money transfers … .” Since then, Western Union has been in discussions with the FTC “to reach an appropriate resolution,” according to SEC documents.

When Mike and his girls arrived back at his pickup truck, he spotted a Santa Barbara Police Department squad car nearby. “Mr. Tognotti ran up to me pretty frantically, and his two girls seemed pretty shaken up,” remembered Officer Matt Tonello, who was in the area on patrol. As Mike replayed the details of Audrey’s kidnapping and ransom payment, Tonello got suspicious. A kidnapping in Paris with a wire to Mexico? Tonello knew it was phony. He’d heard of schemes like this and had experienced something similar firsthand five years ago when he and fellow U.S. Marine Reservists checked their cell phones at a border crossing between Hungary and Romania. Their data chips were hacked, and their parents back home started getting calls that their deployed sons had been kidnapped.

Tonello wanted to prove to Mike that Audrey was okay. He asked Mike for her number. Mike was apprehensive; he put his caller on mute and argued with Tonello that it wouldn’t go over well with her kidnappers if she got a call from a cop. But Tonello planned to play it cool. He’d pretend to be an old friend, calling to remind her to bring back a few nice bottles of French wine.

Mike agreed, and Tonello made the call. When Audrey picked up, two things quickly became apparent to the 11-year law-enforcement veteran: Audrey was not in danger, and she was beside herself with grief.

It turned out that just moments after Mike had wired the $1,000, Audrey’s caller had told her that Mike had not cooperated and that little Addy would pay the ultimate price and her body dumped somewhere in Mexico. Then he hung up. “I fell to my knees and cried and cried,” Audrey remembered, a tremendous sadness overcoming even now.

Realizing that Audrey was not in danger, Tonello quickly went off script, explaining to Audrey that he was with the S.B. Police Department and that he was with Mike and the girls. Audrey didn’t believe him. Tonello handed his phone to Mike, who was still on the line with his caller. “Audrey! Thank God! Are you okay?” Mike said into Tonello’s phone as he hung up on his caller. She said, “What do you mean am I okay? What about Addy!”

“She’s right here with me,” Mike replied, perplexed.

Audrey didn’t believe him. She was sobbing on a Parisian sidewalk, in the middle of the night, halfway around the world, and she’d just been told that she’ll never see her daughter again, alive or dead. Mike put Addy on the phone. Audrey still wasn’t convinced. She shook her head and looked around her, noticing Spence and the couple from the U.S. Embassy who just so happened to be walking past the bookshop at a critical moment. The thought crossed Audrey’s mind: Maybe these people are in on it …

Mike called her back from his own phone, told her the date of their wedding, where it was held, what they had said to each other at the birth of their firstborn, intimate facts that he hoped would convince Audrey he was who he said he was.

A call came through on Mike’s phone — an overseas number. Mike put Audrey on hold and picked up. It was a man claiming to be with the U.S. Embassy in Paris. Mike didn’t believe him and hung up. Back with Audrey, Mike tried FaceTime, but there was no connection. He tried to text her a picture of him with the girls, but it didn’t go through. Finally, he posted a proof-of-life photo on Facebook, where Audrey was finally able to see it. At last, a flood of relief.

The Final Sweep

In Paris and Santa Barbara, phones got passed around as the family reconnected. “We were so relieved,” remembered Danielson. “And I’m the grandma, so I worry about them all.” In the bookstore, there were big hugs all around. “They seemed like angels,” Danielson about the helpful strangers. “After it was over and we were all standing there in the middle of the night, I thought they would disappear before my eyes.”

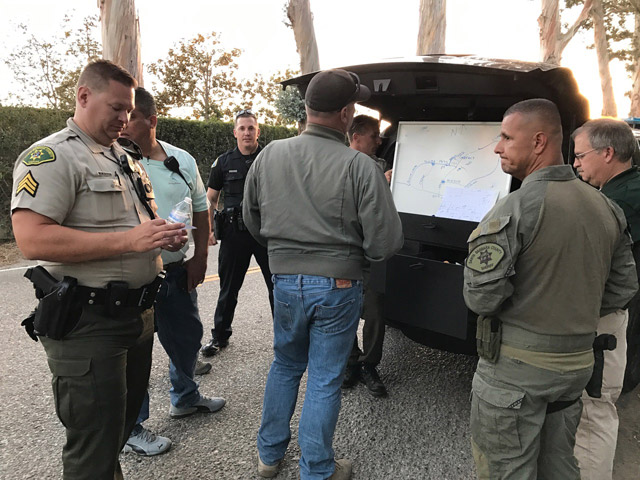

Meanwhile, outside the Tognotti’s Montecito home, the Sheriff’s Special Enforcement Team (SET) and Hostage Negotiation Team were preparing for the worst. They had gotten a report from the U.S. Embassy in Paris of a kidnapping, possibly carried out by a Mexican cartel. The already tense situation was exacerbated by the close proximity of the Tognotti’s home to that of an alleged bookmaker for an East Coast gambling syndicate who was arrested for corruption and money laundering in 2012.

When Tonello got the news, he notified Sheriff’s Office dispatch that the Tognottis were safe, and then he escorted Mike and the girls home, where they found the street taped off and SET officers wrapping up their sweep of the empty house: all clear.

Mike decided it was too much anxiety for the whole family, so he called a friend, who put Mike, the girls, and their pets all up for a few nights. In the coming days, however, Mike began to share his story with fellow school parents and church groups to let them know his family was okay and to get the word out about virtual kidnapping.

Back in Paris, Audrey and Danielson decided not to let the terrifying experience cut short their Parisian vacation. After all, it was Danielson’s surprise birthday trip, and they’d only been there three days. They had a lot more sightseeing and celebrating to do. The next night, Audrey and Danielson took their “angels” out to dinner. It was a five-hour feast.