The Santa Barbara Independent’s Local Heroes of 2016

Twenty Local Heroes Who Make a Difference

As Will Rogers once famously said, “We can’t all be heroes, because somebody has to sit on the curb and clap as they go by.” Well in this, the annual Thanksgiving issue, the staff of The Santa Barbara Independent once again seeks to honor some of the truly great heroes living among us. These are the men and women whose work helps keep decency, kindness, and generosity alive in our county. They are the men and women who, just going about their daily lives, bring us closer together, replenish the spirit of community, find ways to help the vulnerable, and give a voice to those in need. Most are not public figures and few have accomplished earth-shattering feats, but all have stepped up to do their very best. We are humbled by and grateful for their efforts, and we hope you will join us on the curb to clap and cheer for The Santa Barbara Independent’s Local Heroes of 2016.

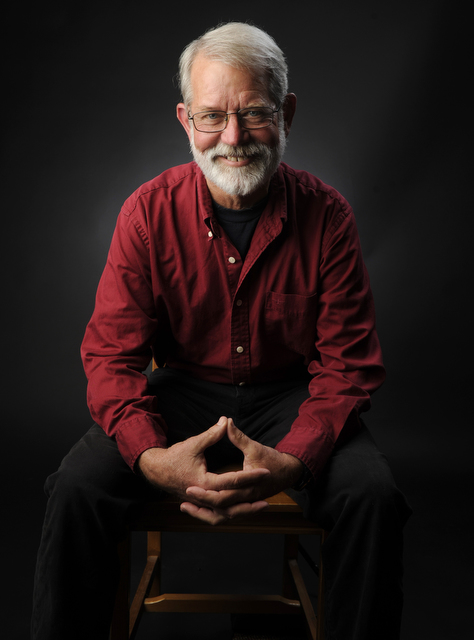

Dennis Apel: Peaceful Warrior

Denis Apel is endowed with an easy laugh but a very stubborn conscience. A peace activist with the Catholic Worker Movement, he is perhaps best known for his civil disobedience, having been arrested in front of Vandenberg Air Force Base more than 20 times. He recently spent four months locked up in a federal detention facility for crossing Vandenberg’s “green line” while observing the 70th anniversary of A-bombing Hiroshima. For two weeks, he was held in quasi-solitary confinement because he wrote about his jailhouse experience in the pages of The Santa Barbara Independent. “We’re not as free as we like to think we are,” he noted afterward. Apel famously sued the government for dictating where he could and could not protest and took his case all the way to the Supreme Court, where it was shot down. But more quietly, Apel and his wife, Hortencia Hernandez-Apel, have been providing free food, emergency housing, medical treatment, English instruction, and advocacy work from their Guadalupe headquarters for immigrant farmworkers.

As a result, 150 families a week can eat, hundreds of women fleeing abusive relationships find shelter, and six doctors are on call to make sure the sick get care. A truck salesman in a previous incarnation, Apel knows how to bargain, so now area hospitals provide $45,000 surgical procedures at reduced charges. In addition, he and his wife offer advocacy services, helping people secure workers’ comp protection and Social Security payments. For 20 years the Apels have been helping those living outside the system. “They were on the margins long before we came. They’ll be here after we’re gone,” he said. But in the meantime, it’s his mission to see they’re served. “They’re human beings. They need to be treated as such.”

Yvonne Ashton: Micheltorena Mediator

Every atom needs a nucleus. For the Micheltorena Street Neighborhood Association, it was Yvonne Ashton. She led the successful charge to stop a City Hall plan for an east-west bike lane that would cannibalized about 80 on-street parking spaces along Micheltorena Street. Most impressive was how she helped make the bike-lane proposal bigger, better, and safer. Ashton chuckles that she was “just an idiot in the room,” taking notes and reporting back. One look into her wintery blue eyes, however, says otherwise. Last October, City Hall suddenly announced it was re-striping four blocks of Micheltorena from State Street to Castillo Street to create a new bike lane. By February, the City Council was poised to vote. Many neighbors were outraged at the loss of parking. Ashton — who owns several commercial properties in Santa Barbara — put her money where her mouth was, hiring an attorney, a land-use consultant, a political consultant, and a traffic engineer. Thanks to these early interventions, fatal flaws in the city’s proposal quickly came to light, and the City Council was forced — admittedly, at the last minute of a late-night meeting — to explore new design options.

Although Ashton herself doesn’t ride, cyclists — both commuters and former racers — played key roles in the opposition team she helped sustain. Together, they negotiated a deal with City Hall and Bicycle Coalition advocates to locate a new east-west bicycle boulevard along Sola Street that would separate cars from cyclists more safely, extending it several blocks farther east than the original Micheltorena Street plan. Because of these changes — coupled with the broader base of community support they engendered — City Hall just won under $5 million in state transportation grants.

Kristianne Clifford-Schell: Freedom to Forgive

Kristianne Clifford-Schell was a Goleta kid and a self-described daddy’s girl, whose father died of a stroke when she was 12. Soon after, she began filling the hole in her heart with drugs and alcohol. Ten years of heavy use combusted in a six-week, meth-fueled spree that left a man dead. Clifford-Schell was sentenced to 15 years to life in prison. That was 1995.

A decade into her sentence, Clifford-Schell attended a self-esteem workshop for “lifers” put on by the Freedom to Choose Project, a support organization created 12 years ago by two Santa Barbara psychologists. The women learned how to start forgiving themselves and how to move through their denial, shame, and guilt and find value in the rubble of their lives. “All I could do was cry,” remembered Clifford-Schell. “I think that was the first time I had allowed myself to feel emotion since I was arrested.” Among the workshop literature was a motivational maxim she’d never forget: “Be the change you wish to see in the world.”

In the years since, Clifford-Schell has truly become that change. She was paroled in September 2012 and is now Freedom’s program coordinator, connecting the organization with prisoners around the state. For security reasons, former convicts typically aren’t allowed back inside detention facilities. Knowing how much more meaningful the workshops would be coming from a reformed convict, Clifford-Schell repeatedly petitioned the state before she was allowed inside. “I spent 18 years trying to get out of prison, then spent the last four years trying to get back in,” she laughed. Soon, she’ll start a pilot program here at the Santa Barbara County Jail. “If I can help someone not make the same mistakes I did,” she said, “then that’s what I have to do.”

Ann Lippincott: Mental Health Matters

Inspired by her own mentally ill daughter, Ann Lippinncott — who spent 34 years at UCSB teaching teachers how to teach — created a 6th grade curriculum to destigmatize mental illness. Lippincott emphasizes three startling but obvious truths: One in four families will experience a serious mental illness. For half of those afflicted, symptoms present by age 14. And the sooner the treatment, the better the outcome. There have been programs designed to teach mental-health awareness since 2000, but they’ve been lining the school district’s circular file because no teacher has any extra time to give to another subject. So Lippincott crafted a highly interactive curriculum on mental illness but packaged it as part of the state’s mandated Common Core program for English Language Arts. The program started in 2008, involving just one classroom and a handful of students. Today, it’s taught in 35 classes to about 1,000 students. When studying mental-health issues, 6th graders are taught to take notes, read texts, make oral presentations, work in teams, create posters, and, of course, use similes, such as — as one student put it — “having attention-deficit hyperactive disorder is like an ant farm in your head.” Students learn the symptoms for major mental illnesses and that they can affect anyone — not just the homeless. Lippincott and her group of dedicated volunteers stress that mental illness does not define who you are. “It’s not something you are,” she said. “It’s something you have.”

Pat McElroy: Fixing the 9-1-1 Lifeline

You might not know it, but 9-1-1 systems across the country — including California’s — are a mess. They’re so old and outdated that they can’t pinpoint the location of emergency calls made from cell phones, and they regularly misroute calls to dispatchers in the wrong city. Wires get crossed, precious minutes tick by, and ambulances are delayed. The Federal Communications Commission estimates that more than 10,000 Americans die every year because of this.

“Think if 10,000 people were dying every year from the Zika virus,” said Fire Chief Pat McElroy. “That wouldn’t be acceptable. This shouldn’t be acceptable, either.” Since 2014, when a 24-year-old Santa Barbara woman died in her parents’ arms as they frantically repeated their home address to a dispatcher in Ventura, McElroy has led a crusade to modernize the state’s 9-1-1 system. His brother’s untimely death under similar circumstances three years earlier drives his efforts, too. “How can Uber and Domino’s find you, but 9-1-1 can’t?” he asks.

Although a solution is still frustratingly far off, McElroy has succeeded where tech engineers and state bureaucrats have failed: He’s articulated the complicated issue in digestible terms and is successfully raising awareness about its real toll on human lives. He also had a hand in new legislation to bring the public lifeline into the 21st century and is regularly bird-dogging Sacramento to fix individual routing problems in Santa Barbara as he discovers them. “We need a systematic approach,” he said of the state’s obligation to public safety, “not a pain-in-the-ass fire chief playing Whac-A-Mole.”

Willie Poindexter: Teacher of Kindness

“I just loved on those kids,” Willie Poindexter said about how he was able to reach through invisible bars and touch the troubled teens he counseled at Los Prietos Boys Camp in Santa Barbara’s backcountry. “My secret is that I listen,” he said. “Extra big patience. I listen to them.”

Poindexter has since retired from Los Prietos, and, as a master teacher in kung fu, he now teaches probation officers the rules of and procedure for arresting a suspect. But his greatest impact lives on in the talks he had with Los Prietos’ young men about fatherhood. “Boys, you know, boys just think it’s a macho thing to have a child,” he said. “I got really personal with them. In a really kind way, I’d say what a responsibility they have. Things change when you have a child. You can’t do that when you’re in trouble.”

Raising self-esteem and creating “an environment where they feel good about themselves” was Poindexter’s specialty. “Every day they’re challenged with their self-esteem,” he said of the young women in Probation and at Juvenile Hall, “especially the girls. I was a court officer, and they all knew I had a daughter — 5 or 6 at the time. One of them asked, ‘Hey, Willie. What would you do if your daughter was locked up?’ I said, ‘I would tell her I loved…,” and she was in tears before I got all the words out.”

Some newcomers to Los Prietos couldn’t figure out why Poindexter was so gentle but had widely admired his martial-arts skills. He’d use humor to defuse the ones who wanted to fight, and the kids would ask, why not kick ass? “It’s not like that,” he’d reply. “You do the opposite. You just have all this love inside of you, and you just can’t keep it all to yourself. It’d be like having a party without anyone there. You got to have other people there.”

Jeff Shaffer: A Helping Hand

For nearly 15 years, Jeff Shaffer was a pastor at Community Covenant Church in Goleta. Then, in 2002, while contemplating centuries of religious art at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, he had what he describes as “a calling.” The message was clear: Instead of inviting people to church, get out and spend time along the margins, where people need the most help. Shaffer started by serving homemade spaghetti to the homeless at Pershing Park. He was consistent and funny and a really good listener. Before long, his Uffizi Mission Project — now called the Uffizi Order — gained momentum, attracting volunteers and other outreach groups to the table. To coordinate resources, he helped start Common Ground in 2010. Shaffer says the meal sharing, which has since expanded to Alameda Park, “is really a vehicle to build relationships” with Santa Barbara’s homeless. Once that foundation is established, support networks aim to keep a person on track through phases of ascension, from sobriety to shelters to employment to — and this one’s the toughest — affordable housing. That final piece of the puzzle is a pillar of his coordinating work countywide with the Central Coast Collaborative on Homelessness. And it also informs his newly forged collaboration with the Resiliency Interventions for Sexual Exploitation (RISE) project to find housing for survivors of sexual exploitation and human trafficking. The calling continues.

David Asbell: Directing the Lobero

It was almost exactly 20 years ago that David Asbell accepted the position of executive director at the Lobero Theatre. The venerable structure on East Canon Perdido Street was on the verge of one of its all-time least successful ventures, an ill-fated attempt at establishing a professional repertory theater. If it had gone forward, it would undoubtedly have bankrupted the Lobero within a matter of months. Asbell, freshly arrived from Atlanta, already knew something about Santa Barbara — he had grown up working in his father’s orchid greenhouse on the Mesa — and he knew a lot more about the performing arts.

A veteran of stage management with more than a decade’s experience with the Atlanta Ballet and earlier with a Shakespeare festival in Birmingham, Alabama, he not only brought the kind of savvy that only comes from working backstage, but he also brought a profound vision of what the Lobero Theatre could become: Santa Barbara’s beating creative heart. With characteristic humility, he points to the venue’s 600-seat capacity as the key to its success, but those of us privileged to spend many captivating evenings there know better. By establishing a welcoming atmosphere and by being open to a creative team that includes such area luminaries as Hale Milgrim, Dianne Vapnek, Peggie Jones, and Stephen Cloud, Asbell has turned the Lobero into what we need most, in good times and bad: a blessed community of like-minded people, alive to the arts and ready to listen and share the love of great music, ideas, dance, and theater.

Bruce and David Corwin: Open-Armed Theater Owners

Santa Barbara’s movie houses are all owned and operated by Metropolitan Theatres Corporation, and we are lucky to have such a magnanimous monopoly. That’s thanks to the Corwins, the fourth-generation theater family from Los Angeles who first entered the Santa Barbara scene in 1948.

Led today by Bruce and his son, David, the Corwins constantly give away thousands of tickets to students and nonprofits, such as Unity Shoppe and Girls Inc., and frequently grant other organizations the use of their facilities for film festivals (including, most recently, Pacific Pride’s OUTrageous and the African Heritage Film Series), fundraising concerts, educational lectures, and more. They were also integral in starting and growing the Santa Barbara International Film Festival, and every year they open the entire Arlington Theatre to the community for free-to-see top family films while enjoying free popcorn during the festival’s AppleBox series.

“We’ve always been involved in the community,” said Bruce, who also engages in a wide range of philanthropy around the country, from donating to UCSB and Wesleyan University to supporting Jewish causes, health foundations, and research on multiple sclerosis (MS), which he’s battled for many years. “The bottom line is that making money has never been that important to me in particular. It’s important to show leadership and involvement with the nonprofit world. That’s what we’ve tried to do.”

“He’s so selfless,” said David of his dad, noting that Bruce frequently gives career guidance to young people and even basic help to those suffering from MS. “I walked into his office one day, and he was in there literally showing a woman how to shoot a needle into an orange.” Raised in such an environment, David is naturally inclined to help nonprofits raise money by using his family’s venues, despite the challenges that presents to their bottom line. “I’m the more straightlaced numbers person, and he’s the creative giver,” said David. “Over time, we have found a happy middle ground.”

Joan Fairfield: Witness Advocate

Pinned to a corkboard in her office is a collection of photographs of the dozens of people Joan Fairfield has guided in her role as the victim witness advocate at the District Attorney’s Office. Over the years, she has kept in touch with some victims because they had to return to court to testify at parole hearings. But many maintained a personal relationship with her long after their case closed.

In 1979, Fairfield was hired by then-district attorney Stan Roden after she had been a stay-at-home mom for 18 years. “She was genetically wired for the job,” Roden recalled. A victim advocate must delicately balance an understanding of legal language with compassion for people often just scarred by a violent crime. For 37 years, Fairfield has done both.

For Fairfield, the job is equal parts fascinating and encouraging. “I am constantly impressed by what people can overcome and how powerful the human spirit and human body are,” she said. She has found that victims “are just like the rest of us — different in every way.” Some are doe-eyed and innocent-looking as one would expect, but others are more complicated. So Fairfield must alter her approach depending on with whom she is working. For instance, recently in her office, a young girl proved to be resistant. “I said to her, ‘I’m going to talk to you like your grandmother: You are precious, you should be cherished, people love you. Please know you are worth being cared for — not abused.’ I hope she believes those things, because I believe it.” With other clients, she has to be firmer: “Look, this is the way things work. You have a subpoena. It’s not an invitation to a party. There is no RSVP.” Ultimately, she said, “I try to be real with people.”

Alagie Jammeh: Fighting for Human Rights

In 2014, Gambian Alagie Jammeh, a UCSB student, posted on Facebook: “No one should be denied their fundamental human rights because of their sexuality.” This drew outrage from his home country, where same-sex relationships are illegal. His own family disowned him, and the government revoked his scholarship. As a result, Jammeh lost his apartment, had to sleep in his car, showered at the Rec Center, and feared for his life. Eventually he was granted asylum. Jammeh stands as a hero to many as someone who dared to speak his beliefs; he has received phone calls from LGBTQ people around the world, and it is their stories that continue to motivate him.

“You cannot just stay quiet, because there is someone who, all his life, has been struggling, trying to fit in this society that will never accept him, that will kill him,” he said. “I feel I have a duty … for thousands and millions of other people around the world that don’t have the platform or environment to express themselves, to be themselves, to smile, to go to work and come home and be loved by someone who will love them back. They are part of this society, and it is our responsibility … to say, ‘I will fight for you. I will fight with you. I will go to things that will make you the same as me.’” Jammeh is not concerned exclusively with LGBTQ rights but also the rights of “women, children, and religious minorities” and is hoping to work with a human-rights organization after graduation. Jammeh feels sad to leave UCSB and the community he found there, but he is grateful for what it taught him: to examine his inherited beliefs and change them for the better. “This university taught me to question everything,” he said. “It’s the best thing I have learned in America.”

Gary Sangenitto: The Bass Player

Bass players have no business being named a Local Hero, according to Gary Sangenitto. And he should know — this father of two has been the bass man in a dizzying number of Santa Barbara–based bands over the past five decades and counting. “I am a roofer and a musician,” offers Sangenito. “I have had all my friends do better than me. I am not even the lead guitar guy, you know. I play bass.”

Arriving to town from San Francisco’s East Bay as a freshman at UCSB in 1971, Gary has been calling the South Coast home more or less ever since. His unbridled love of music and his unflinching willingness to share that passion has shaped much of his time in town and has provided the soundtrack for an unfathomable amount of fun. His band résumé includes well-known outfits of the past and present such as The Tan, The Wedding Band, Ulysses Jasz, and Tortilla Flats to name but a few. And then there are the countless ways he uses music to give back and grow the community, such as lending musical equipment and gear for events large and small, playing in the house band for youth empowerment program AHA!, or, when his children were still young, playing in the Grateful Dads band at Roosevelt Elementary School. And then there is his personal collection of more than 20,000 albums. “I have a hard time saying no,” he said.

But more to the point, Sangenitto has a hard time not being an excellent human. “I always tell my kids, ‘It’s not about the money.’ You can find that dollar somewhere else.” He explains with an air of unworried ease that can best be described as Buddha-esque, “It is more important to find what you love and then find a way to share that with the world. Oh, and don’t forget to listen.”

Jason Emrich: An Answered Prayer

Smart money says, if you’ve been to Santa Barbara’s Home Improvement Center with even a modest amount of regularity over the past two decades, then you already know the world-class helpfulness that is Jason Emrich. Tall with sympathetic brown eyes, a gentle disposition, and a warm smile, Emrich has been a mainstay at the hardware store’s paint department for much of his 24 years as an employee. His near-clinical attention to detail, coupled with a vibrant and genuine commitment to customer service, transcends the retail experience. It is not hyperbole to say that Emrich’s palatable humanity often elevates the simple act of buying some new paint for your bathroom into something both memorable and refreshing. But his value to his coworkers and customers goes beyond the base requirements of his job — far beyond. Consider the fact that each week Emrich reaches out to one of his former bosses, a man long since retired and relocated to Florida, to read him books over the telephone now that his eyesight is failing.

The youngest of three, Emrich, born and raised in Goleta, was 24 when he first landed at the Home Improvement Center. What was initially meant to be a six-month temp job at the register soon turned into a career. It had been a dark time for the devout Catholic, and “I was asking the Lord for something to help me on my path,” recalls Emrich. “I definitely got what I was asking for.”

The Dos Pubelos graduate, who is often approached by grateful past customers while just waiting for his order at a coffee shop, is uncomfortable with the praise. “Just always trying to slow down, be present, and do better” is what Emrich offers as an explanation for his success. “Learning about people and myself, that is what it all comes down to no matter what job you do.”

Jennifer Parks: Our Motherly Mortician

Modern Americans are so removed from death that a motherly mortician seems more fantasy than reality. But that’s the work of Jennifer Parks, the general manager and funeral celebrant at McDermott-Crockett & Associates Mortuary.

“We get to be their storyteller,” said Parks of the deceased people that she cares for and their grieving families, many of whom are devastated by sudden loss. “We speak for them when they cannot breathe. We hold together every piece of their heart.”

Formerly a doula in San Francisco, Parks initially turned down the job when it was suggested by a friend whose family owned the mortuary, but in 2004, she gave into her “servant’s heart” and accepted. She’s embraced the role ever since, even when that means doing plaster casts of dead infants’ feet or tending to the young victims of some of Santa Barbara’s worst tragedies. She also stands in for the unclaimed deceased of the tri-county region each year when their ashes are spread at sea, hosts an extravagant Valentine’s Day party for those who’ve recently lost their sweethearts, and runs a quarterly series of life-skills classes, such as cooking for one.

Though she’s not a grief counselor, she often acts as one, providing a “lifeline” to parents, siblings, children, and spouses of all ages as they weave through the funeral process. “Really listening is the most important thing,” she said. “People want to tell their story, that they were here and they were important.” To her, it’s very similar to her past career in childbirth. “This work is sacred, whether you’re coming in or going out,” said Parks. “This is incredibly personal and intimate, and it’s a huge gift to be able to hold them in my hands.”

Doug Mershon: Tutor and Friend

For the past six years, Doug Mershon has commuted from his home in the mountains to Santa Barbara’s Lower Eastside, where he volunteers five days a week at Franklin Elementary School. The kids always light up when he arrives, screaming, “Mr. Doug! Mr. Doug!” The schoolchildren’s happiness may seem a bit odd, though. After all, he’s there to teach them the most-feared subject of all: math. But with a tutor like Mershon — reliable, determined, patient, and kind — the kids’ fear fades and the learning begins. “I help them with their basic skills to keep them from slipping behind,” says Mershon, a retired electrician and a former teacher, credentialed at UCSB. Lately — in addition to a Habitat for Humanity bathroom renovation for an elderly disabled couple — Mershon’s been working with a handful of Franklin 3rd graders during recess and then helping out in a 4th grade classroom.

Sometimes he’s tutoring and reviewing test scores with big groups; other times, it’s just one-on-one. Either way, the extra push he provides goes a long way toward instilling the kids with a sense of identity and self-worth in classrooms with 28 students per teacher. “The kids appreciate the individual attention,” he says, “and they like it when I speak a little Spanish, too.”

Magda Barnes: Awash in Love

Clean clothes: a necessity, perhaps taken for granted by some, but for many Santa Barbarans it poses a real and costly struggle. That’s why Magda Barnes helped launch the S.B. chapter of Laundry Love, a network of community partnerships nationwide between volunteers and laundromats, offering free clothes washing and drying and soap to the homeless and those living below the poverty line. Barnes launched Laundry Love six years ago at the House of Laundry on Milpas, helping to improve the daily lives of many.

Barnes credits her mother for raising her with a spirit of service, encouraging her when she was a kid to engage with her community, whether through her church or the Rescue Mission. Her early experiences taught her to “be patient and be caring and compassionate” toward others. “As a Christian, that’s part of my belief model: what Jesus did, to love even the most unlovable.”

So much of what Laundry Love offers, Barnes says, is a sense of community — a chance “to be seen, to be heard, to be loved, and to be accepted for a couple hours.” It not only serves the homeless, but it also helps to bridge gaps in communities where interpersonal and institutional barriers have created voids. “The only way to change that is if people are united and make the step towards understanding each other.” Barnes is now off to Dubai to continue her mission of service in a different community, but her work will continue. All interested readers can form a Laundry Love in their own neighborhoods.

Mark Asman: A Priest for All Seasons

A priest for most of his adult life, Mark Asman, the recently retired pastor of Trinity Episcopal Church, has taken on the struggles of the voiceless, whether it’s the hungry, the homeless, the poor, the young, or the LGBTQ.

“When I came to Santa Barbara in 1994,” Asman said, “the city was divided over an ordinance to ban sitting as a way to criminalize the homeless on State Street.” He’s quick to praise the religious and business leaders who helped found the Casa Esperanza homeless shelter in 1999 as a better solution, but everyone agrees that most of the credit belongs to Asman. Trinity was already active in social justice before Asman became pastor, including opening a community kitchen that evolved into today’s Transition House. But he nudged things a little further, including increasing Trinity’s support for Planned Parenthood and leading the church to become one of the first to open its parking lots for overnight stays for the homeless. He praised his congregation for accepting him as an openly gay priest and for supporting same-sex marriages. “Rather than civil unions, we would perform marriages.” The first one was 17 years before it was finally legalized in California. “What quietly frustrates me,” he mused, “is how many people perceive Christianity, and religion in general, to be irrelevant at best and dangerous at worst. For people of faith to be absent from issues of great justice is not where we should be. We should be on the forefront.” He sighed deeply, distressed by the national election result and how seriously it would affect Dreamers — college students attending public institutions without legal papers. “It’s another thing to see lives ruined by this man.”

Patsy Dorsey: Running Wild

“The Patsy Dorsey waterfall effect is quite striking,” said one of her many friends. “It is felt all over town.” For 70 years, Dorsey, who grew up on Garden Street with six sisters and three brothers, has been deeply involved in Santa Barbara. And although she leads a fairly normal existence, she brings an unbeatable spirit to every aspect of her life. In many ways, she is the classic Local Hero. As a young person, she supported her gay brother before it was cool. After he died of AIDS in 1990, she rode in a benefit bike ride in his memory. Later, she raised four kids as a single mom, working multiple jobs, saving every dime, and eventually buying her own house. But she isn’t all about keeping her nose to the grindstone. In fact, she is unabashedly unbridled — in her sixties, she was still dancing freely at bars in Mexico. Asked if she always had a wild side, Dorsey said she thinks it seems to have flourished as she has grown older. “I’ve always been precarious,” she said, laughing. “Maybe a little too precarious sometimes.” In a less perilous vein, she founded the Nine Trails ultra marathon. Soon, she found herself running marathons and later 50-milers, and she kept her wild side alive by flashing her running crew every year at the 11th mile of the Pier to Peak run. Though she can no longer run these days, she’s proud that she has finished more than 100 marathons. And even though she describes herself as a “back-of-the-packer,” she can’t help but get a kick out of being the female winner of a 1990s Arizona marathon — of course, she was the only woman in it. When she started running, she recalled, very few women were signed up. Now she sees just as many women as men, if not more. “That is really inspirational,” she said.

Lee Heller: Animal Advocate

Although she was “the kind of kid who was always bringing home the stray dog,” it wasn’t until her early twenties that Lee Heller was introduced to animal-welfare issues. “In between college and grad school, I worked at the Chicago Anti-Cruelty Society. I was actually just a phone operator, but I saw firsthand what a big inner-city shelter was like,” she said. After earning her PhD in English and spending 13 years as a professor in Massachusetts, Heller left academia, moved to Santa Barbara, and focused full-time on her activism. “I got involved just walking dogs at the county animal shelter,” she said. “That led to fostering dogs and cats — one year, I think I fostered like 60 kittens in a season [for ASAP],” she said. Heller also helps behind the scenes, writing grants for area agencies, which are always in need of funds. “I’ve written grants for CARE4Paws, Diana Basehart, ASAP, Shadow’s Fund, Santa Maria Valley Human Society, and County Services, [among others],” she said. “I’ve probably brought in — if you added up everybody’s numbers — $300,000 or $400,000 in grant money into the community.”

Policy work is another part of her advocacy, which has included getting spay/neuter ordinances passed in Santa Barbara County and getting county legislators to endorse bills that protect animals, such as the recently passed California AB 1825, which redefines the assumption that any dog seized as part of a dog-fighting operation is classified as vicious. For Heller, activism comes naturally. “I was raised in a household where civic engagement was always ongoing. I was just raised believing that this was meaningful [work],” she said. “There are so many animal nonprofits, so many ways to match up what you care about with what an organization is doing, and it’s really exciting and wonderful, and what an opportunity to be part of that.”

Barbara Ireland: Fundraiser Extraordinaire

Barbara Ireland made a decision to help women with breast cancer after one of her close friends was diagnosed. Sixteen years later and Ireland’s name is now synonymous with an annual event that sees 500 or so folks gather to raise funds for cancer research. The Barbara Ireland Walk and Run for Breast Cancer was born in 2000, when Ireland approached the Dr. Susan Love Research Foundation and proposed doing a fundraiser in which all the money would go to breast-cancer research here in Santa Barbara. Love and her board liked the idea. “We started out doing a 13-mile walk in Montecito,” said Ireland.

These days, the event offers the option to walk or run one of three courses — a 5K, 10K, or 15K — along the downtown waterfront. When Love moved out of town in 2005, Ireland partnered with the Cancer Center, which does cutting-edge research in town. “They asked if I’d give them five years, and I said yes.” The five years turned into 11. “It’s been fun, and it’s been good, and we get some great people who come out the day of the walk,” said Ireland. “It’s such a loving feeling on that day; they are all there to help this cause, and they have a good time doing it.” This year’s event, which took place in March, raised nearly $69,000. As for the future of the Barbara Ireland Walk, she said: “As long as it’s still helping people, we will continue to do it.”

• View previous Santa Barbara Independent Local Heroes