Rattlesnake Canyon Trail

The Basics

Distance-.75 to the first creek crossing; 2.5 miles to the connector trail leading to Tunnel Trail; 3 miles to the intersection with Gibraltar Road

Elevation Gain-200′ to the first creek crossing; 1000′ to the connector trail leading to Tunnel Trail; 1550′ to the intersection with Gibraltar Road

Difficulty-Moderate

Topo-Santa Barbara

GETTING THERE-From the Santa Barbara Mission drive up Mission Canyon Road to Foothill. Turn right, then left several hundred yards later (by the fire station). Continue up Mission Canyon past Tunnel Road to Las Canoas. Turn right and continue a mile and a half to an open area immediately preceding a narrow bridge. You’ll find a large sign there noting the start of the Rattlesnake Canyon Trail.

HIGHLIGHTS

Rattlesnake Canyon is filled with cascading waterfalls and deep pools. The alder cover provides shade and a lovely green canopy. If you hike up the creek from the trailhead or take one of the many side trails leading down to the creek you’ll find the remains of a dam built in the early 1800s to service the Mission. Within just a few minutes drive from downtown Santa Barbara you can be hiking up this picturesque canyon, lost in its wilderness beauty. A connector leading to Tunnel Trail makes it possible to hike all the way to the crest.

I have always loved the drive up Las Canoas to the Rattlesnake trailhead. The houses are beautiful and the countryside suggests a wildness unusual for its close proximity to the city. Situated on the back side of the Riviera, thick oaks are found on the shady hillsides in sharp contrast to the open wildflower and grass-covered slopes of the sunny side of the street.

Arriving at the entrance to the canyon is a treat in itself. The narrow, sandstone block bridge is quaint, a reminder of times when this was truly wild country. Skofield Park is on one side of the bridge, thirty-five acres with activities ranging from overnight camping to volleyball and BBQs. The wilderness park is across the road on the north side of the bridge. Its hiking trail which will lead you into the upper end of the canyon, and if your legs are willing, routes over into Mission Canyon or up onto Gibraltar Road for a bit of relaxation at the edge of the ice-cube shaped rock where climbers can usually be found clinging to the wall.

Rattlesnake Canyon has seen constant activity since early Mission days. In the 1790s, water was supplied to the Mission and the Presidio through a ditch from Mission Creek-thus giving Las Canoas it name: canoas in Spanish means “flumes.” These flumes funneled the precious water flowing down Rattlesnake Canyon into Mission Creek for use during periods of scarcity. Chumash helped dig the channel and lay the tiles lining the flumes and constructed a temporary dam of brush, earth, and rocks to store the water.

Eventually, in the years 1790 to 1795, artisans were sent from Mexico to assist in the building of houses and more permanent water storage facilities. Initially a large stone dam and an aqueduct were built in Mission Creek and in 1808 another dam was added in Rattlesnake Canyon. With Indian labor the fieldstone and mortar structure was built across the creek about a half mile up from Las Canoas Road.

While remnants of the dam still exist, sediments have filled in behind, eliminating the reservoir and carving a V-shaped notch in the middle of the dam. However, the pool below, shaded by alder and bay, and surrounded by wood ferns and the colorful tiger lily still provides welcome relief from the hot afternoon sun.

Rattlesnake Canyon’s more recent history is the product of a single family: the Skofields. Once the entire canyon was owned by Ray Skofield, a wealthy New Yorker who moved to Santa Barbara in the 1920s with his family, including son Hobart.

Hobart took on the role of caretaker for the canyon wilderness area. In the early 1930s he planted a number of pines and placing rawhide baskets on either side of his palomino horse, Hobart packed the young trees in them and started up to the meadow. But apparently the horse bucked part way up the trail when it caught sight of the trees waving from its backside. In the end, Hobart secured the aid of a friend and together they carried the trees the rest of the way, using an old ladder as a carrying platform.

During the next few years Hobart watered the pines faithfully until they were able to persist on their own. Unfortunately, these trees burned in the Coyote Fire. However, in 1966 the Sierra Club took on the project of replanting the pines. On two February weekends 100 holes were dug and six-inch Aleppo pines were planted. Water was carried up from the creek in one-gallon containers throughout the spring, summer, and fall until the following rainy season. As you walk past them when you are hiking in the upper canyon say thanks to Hobart and the Sierra Clubbers whose work made their existence possible.

In 1970, Hobart Skofield helped complete the transformation of the canyon by offering the upper 450 acres of the canyon for $150,000, less than half its appraised value, on condition it be made into a wilderness park.

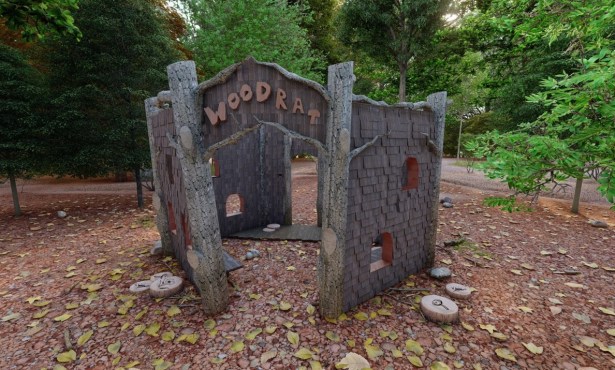

That is why, today, when you visit the canyon, you will see the sign prominently displayed which proclaims this area to be the Rattlesnake Canyon Wilderness Area. In keeping with this tradition of wildness, mountain bikes have been banned from the park, though you may occasionally see an outlaw rider come flashing by.

THE HIKE

The trail begins just before the entrance to Skofield Park near a delicately-shaped stone bridge. From there, cross the creek and follow a short connector trail to a wider dirt road. For many decades this was a buggy road, running alongside the creek to a point about three-quarters of a mile upstream where a prominent layer of sandstone crosses the creek. This was the location of a stone quarry from which much of the stonework in Montecito was derived.

The old buggy road rises gradually through rolling sage-covered hills and the Sespe Formation, then heads back to the creek and the first of a series of narrows created as the stream eroded through successive layers of Coldwater Sandstone during the Pleistocene mountain-building process.

Numerous side trails lead off the main path through the sages to small oak meadows, and they provide access to waterfalls as well as to the old Mission Dam. Beware of the poison oak though!

After the narrows, the trail crosses the creek and follows a set of switchbacks up a steep hill which opens to a large grass meadow marked by a series of Hobart Skofield’s scattered pines. Above the meadow, the trail switches back and forth several more times to a point about 200 feet above the canyon floor. From there it levels for three-quarters of a mile through chaparral shrubs that form a pleasant corridor.

A short drop down to the creek brings you to a cluster of bigleaf maple which seem to guard the entrance to the second of the Coldwater narrows. The walls are vertical and the sunlight generally indirect, as alder and maple crowns filter the sun’s rays, creating a cool, verdant feeling. This is an enchanting place and a worthy spot for lunch or a few minute’s rest.

The next several hundred yards takes you through the narrows and one of the most beautiful canyon sections in the Santa Barbara foothills. Cascading waterfalls, pools, the canopy of alder above you, and the sound of the rushing water make this very special.

A half mile more walking brings you to a large triangular meadow known as Tin Can Flat, for many years a familiar landmark. There, a small cabin was built by a man named William O’Connor. “The homesteading laws required that a dwelling be erected on each section,” according to Public Historian Gregory King, so “O’Connor went into town, collected empty 5 gallon kerosene cans, flattened them, and had them carried back on a mule to a site he liked. Cutting branches from the nearby chaparral, O’Connor quickly put together a frame constructed from the branches and used the flattened kerosene tins to shingle the roof and tack up walls. The floor was provided by Mother Nature-the ground.”

Years later, adventurous boys used Tin Can Shack as an overnight retreat and it was even mentioned in several of the early-day guide books. But shortly after the 1925 earthquake a forest fire burned through the canyon and destroyed the structure. If you are keen-eyed you may still spot some of the tin scattered out in the meadow.

County records show that a 160-acre section was also homesteaded in the canyon. John Stewart built a rough-hewn adobe on the side of a steep hill where he lived for several years. This changed in the 1920s when New York millionaire Ray Skofield moved to Santa Barbara and began to buy up the property in Rattlesnake Canyon, 456 acres in total, from Las Canoas Road to Tin Can Flat. He then started construction of a mansion overlooking the canyon. The work ceased after the Depression began. Later the villa was developed into the Mt. Calvary Retreat.

From Tin Can Flat, which marks the beginning of the Cozy Dell Shale, you can either follow the trail through the meadow, cross the creek to the east side, and hike three-quarters mile up to Gibraltar Road or you can turn left and follow the connector trail up to its intersection with Tunnel Trail, which provides a full day’s loop.

FOR THE ADVENTURESOME

For those who are adventurous several other options are available. After hiking to the upper end of the meadows, instead of continuing on up to Gibraltar Road, turn upstream. In a short distance you will enter a third set of narrows formed in the most dense of the mountain rock, Matilija Sandstone. The hike isn’t easy, but the effort is rewarding. For a half mile a series of waterfalls and pools cascade down the slender channel one after the other.

Eventually you will find yourself climbing up onto Gibraltar Road near Flores Flats, once the home of the Brotherhood of the Sun, and now a private residence. To return the easy way, walk down Gibraltar Road past the climbing area and then take the connector trail back down into the canyon.

Once you reach the narrow canyon below Tin Can Flats, you can also head straight down the creek rather than taking the trail. This isn’t particularly difficult, though it is slower and involves a lot of scrambling. The reward for your efforts will be a quiet solitude and the exhilaration of boulder hopping, my favorite creekside activity. Take care climbing down the many boulders and, of course, watch out for the poison oak. There is plenty of it.

Eventually you will come upon a trail leading down the east side of Rattlesnake Canyon. It is narrower and not as well maintained, but it is abundantly shaded-more a tunnel through the chaparral than an opening, thus providing a touch of coolness on warm afternoons.