Tragedy of Errors

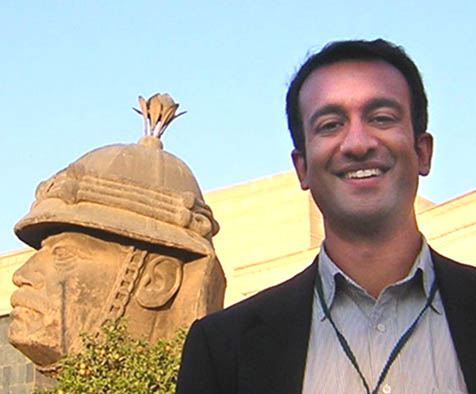

Rajiv Chandrasekaran's Imperial Life in the Emerald City Dissects Postwar Iraq

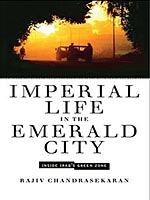

Whether you consider yourself a proud patriot or an ashamed American, go out today and buy a copy of Rajiv Chandrasekaran‘s Imperial Life in the Emerald City. It’s a revealing, engaging portrait of the Bush administration’s sad attempt to rebuild Iraq from within Baghdad’s Americanized and heavily fortified Green Zone.

That ill-fated project continues exploding onto our TV screens every night, and it’s deconstructed vividly in this debut book from California native Chandrasekaran, who spent more time than any American print journalist in Iraq between in 2003 and 2004 as a bureau chief for the Washington Post. Though measured in tone and objective in content, it’s a jaw-dropper that uncovers an astonishing degree of cronyism and cluelessness, leaving you thinking to yourself after each page, “How could this happen?”

I recently asked the same question and others of Chandrasekaran, who spoke over the phone from his office at the Post, where he is now the national editor. He’s coming to UCSB’s Campbell Hall next Monday, October 8. This is the extended version of that interview.

I have a variety of questions, but they all come down to understanding one basic point: How could this happen?

I think that’s a really good question and I would have ventured to answer it at length in the book if I felt like I had a real ironclad answer. But let me give you some theories.

First and foremost, I think the White House and the Pentagon expected a postwar reconstruction would be a fairly simple task. They were diluted by what Iraqi exiles had told them, that the Iraqi infrastructure was fairly modern, that there wasn’t much sectarian conflict, that Iraqis would come together to form a new government. These people lived in exile for 30 to 40 years, and in some cases, the connection to their homeland was very far removed. They looked back on the past with rose-tinted glasses, and figured things would be as harmonious as they remember them

There was also a view to some degree of, “Hey, our army defeated their army in three weeks. We took Baghdad. How hard could it be to run this country? As such, we should send our loyal Republican friends, so they can have their resumes stamped with having served in Baghdad.” That was opposed to having sent the very best and brightest, regardless of party affiliation. There may have also been the view that if things were to go bad, at least let’s have loyalists there so people won’t go home and write kiss-and-tell reports.

When I was first doing my reporting and uncovering these degrees of party loyalty, I was initially in disbelief. But then I put it in a broad context and came to learn how FEMA was staffed during Hurricane Katrina, and I came to:see this as fitting in a larger pattern that was part of the way the administration approached the hiring for important positions.

Where did they learn that hiring tactic?

I don’t think this was something that was invented in Baghdad. I think it was part and parcel of the philosophy that senior levels of the Bush team brought to the government at all levels. Baghdad was just the most shocking example.

Were there any good intentions?

I definitely think there were good intentions. I think a vast majority of the people who went there had good intentions. I don’t subscribe to conspiracy theories about it being all about oil or that we were trying to screw up Iraq because that’s what we wanted.

I think all the people went out there wanting to make Iraq a better place. But like the old saying goes, the road to hell is paved with good intentions. A lot of people who went out there had their heart in the right places-they just didn’t have the right skills up in their head. So we got people who wound up pursuing a bunch of policies that were largely irrelevant to what Iraq really needed:It became a massive exercise in rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

So it wasn’t just intended to fail so that American companies could reap more overpriced contracts?

I don’t believe so. I think what the White House wanted was a successful, peaceful outcome. Did they think that along the way jobs should be handled by private contractors? Yes, clearly, but they didn’t want the outcome to be this. This is not the outcome they wanted, but it’s what happens when you go in without proper preparations.

Your book makes it clear that Iraq never really recovered from the 1991 war. How much of what problems they’re facing now are because of damages sustained then?

The ’91 war and the subsequent sanctions really degraded the infrastructure to a massive degree, despite efforts by the Pentagon to avoid harming Iraq’s infrastructure this time. Just the stress of a war and the collateral damage and the fact that the infrastructure was held together with bailing wire and duct tape, it falls apart pretty quickly. We should have planned for a country with an extremely degraded infrastructure. That was largely knowable, and all the arguments made by the administration subsequently that “we didn’t know how bad it was,” that’s a load of bupkis. The UN was in the country before the war, surveying the Iraqi infrastructure and sending reports back to New York. Then, so you ask, why? And the answer that I venture in the book is that having an honest, open discussion in this country about the true costs of rebuilding Iraq would have been a distraction on the warpath to Iraq. And the administration didn’t want any distractions.

Why not an oil-fueled socialism, at least at first?

That’s what a lot of people who spent time in Iraq were thinking was the most appropriate first step. You essentially start with the economic system they had. It was an oil-slicked economy, centrally planned and fundamentally inefficient. Unlike in Eastern Europe, where there was widespread understanding that the economic system was rotten to the core, Iraqis just figured the problem was the political leadership. Instead of just starting with the political change and making incremental changes to the economy, [Louis Paul “Jerry”] Bremer thought economic change had to go hand-in-hand with political changes. The problem was the Iraqi people didn’t buy into that and, to a degree, they still don’t recognize that their economy is fundamentally dysfunctional. That’s won’t come for awhile. It’s a generational thing. But instead of trying to fix it over time, we tried to introduce big bang capitalism right away. That put people out of work, factories were shuddered, and which foreign investors are going to come into a warzone?

Postwar reconstruction must be messy in any situation, but are there any good examples of doing it right?

The best examples of things going right are the individual people showing up there who broke the rules to get things done. I have a chapter entitled “Breaking the Rules,” and it was part of my effort to shine light on people doing good things.

I liked the little vignettes between chapters that described various bizarre Green Zone scenes. Tell me about those.

I felt like, as I was writing the book, I had these great scenes from the Green Zone that I wanted to us. And I also wanted to reorient the reader back in the Green Zone as the narrative unfolded. I wanted the reader to clearly remember what was taking place and I thought that sort of device would be useful or at least effective in accomplishing that.

I hear the book has been optioned for a movie, and that Matt Damon might star.

Well, let’s keep our fingers crossed. Paul Greengrass, who did United 93 and the latest Bourne Ultimatum, is planning to adapt it. It’s not been confirmed yet on Damon though.

Who would play you?

I’m not sure there would be my character. There have been a lot of autobiographical accounts of journalists who spent time there and I came away convinced that people didn’t need to hear about my life there. People needed to know about what was really happening in Iraq and why we were in the mess we were in.

When the book first came in the office, I had no interest in reading yet another Iraq book, then I immediately liked it once I started reading. But do you think Americans are bored with Iraq?

Of course, many people have reached that saturation point, and they feel like they’ve been inundated with Iraq on television and in the newspapers. The net result is that a lot of good accountability journalism gets ignored. People are ready to accept what administration officials say without consuming-and I don’t want to say “alternative” news soures-but I’m talking the New York Times, the Post, CNN, real media sources that provide ground truth. People are so saturated that they’re tuning out. My hope is that the book and other books will break through that Iraq fatigue, and that’s why I tried to write my book in an engaging wat, to spill it out as a compelling narrative instead of making it feel like a compilation of newspaper articles.

You’re of Indian descent. Do you think that your darker skin made it easier for you to travel as a journalist?

It was a great help. I can sort of look like a dark-skinned guy from Basra as long as I kept my mouth shut and wore ill-fitting Iraqi clothes. But I also had a Washington Post press pass and an American passport, so I could go in the Green Zone whenever I wanted. I felt like more than most people I was able to operate in both worlds.

How much do other reporters get out of the Green Zone?

Most reporters are actually based outside of the Green Zone in fortified compounds. The real question is: How much can they get out and about and talk to people?

How are journalists doing in Iraq, in your opinion?

I think they’re doing the best job possible under very difficult circumstances. The right wing likes to accuse journalist in Iraq of hotel room journalism, but the ones I know are incredibly brave and take huge risks. They’re taking far more risks than members of Congress who fly in for a day.

So can America be exported? Can democracy be exported? Will democracy work in the Middle East?

I lived in Iraq for two years-six months before the invasion and 18 months after-and I have no doubt that the Iraqi people want to live in a democratic society. But, and it’s a big but, they want to live in a democracy under Iraqi terms, a democracy that is organic, that they build themselves. Not a democracy that is foisted upon them by outsiders.

4•1•1

Rajiv Chandrasekaran will discuss his book, Imperial Life in the Emerald City: Inside Iraq’s Green Zone, at UCSB’s Campbell Hall on Monday, October 8 at 8 p.m. Call 893-3535 or visit artsandlectures.ucsb.edu.