A Spectator’s Guide to Sacramento’s Latest Budget Mess

Groundhog Day All Over Again

Shortly after midnight on June 7, 1978, Howard Jarvis dropped his pants for the benefit of reporters gathered in his suite at the Biltmore Hotel in Los Angeles.

The prime mover behind the landmark Proposition 13 tax-cut initiative, which Californians had approved in a landslide a few hours before, Jarvis ducked the press throughout an evening of wild celebration before granting an audience in the first moments of a new day. Jarvis began by recounting a recent fall he’d taken at a TV studio. A spud potato of a man, not abstemious by nature, he then stood up to offer graphic evidence, undoing his trousers to expose white boxer shorts as big as a jib and a livid, purple bruise on his stern, roughly the size of Rhode Island.

Talk about your eyewitness to history.

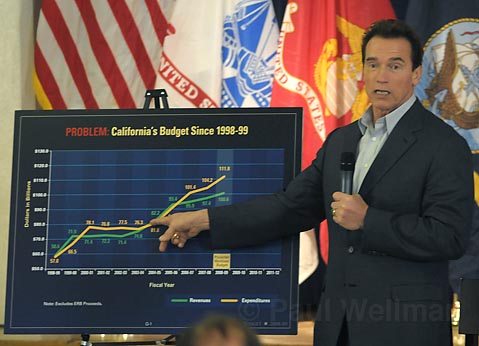

The seared-into-memory sight of Jarvis shooting a moon seemed an apt iconic image this week, as Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger rolled out a 2.0 version of his $100 billion-plus budget for the fiscal year that begins July 1. It was the opening salvo in what Sacramento insiders expect to be yet another summer war of attrition over money for schools and state and local governments, an almost annual exercise since Prop. 13 ushered in California’s modern era of perpetual political procrastination and posturing.

Prop. 13’s passage transformed the landscape of public finance in California, shifting fiscal authority for many programs from local government to Sacramento. Since then, capitol politicians failed in 21 of 30 years-that’s 70 percent-to agree on budgets by the July 1 date. They also totally whiffed in meeting a June 15 deadline allegedly “mandated” by the constitution, often causing fiscal chaos for cities and counties, not to mention people and families who count on the state for food, medicine, shelter, or employment.

In crafting his latest tax and spending plan, the erstwhile Terminator confronted the cruel laws of arithmetic, faced on one side by a threatened revolt from teachers, parents, and school districts over billions in education cuts he proposed earlier and, on the other, a flood of red ink cresting at a $17 billion deficit-$450 for each man, woman, and child in the state. “This is as complicated a set of problems as I’ve ever dealt with,” one veteran backroom budget player told me.

With lawmakers and interest-group advocates still digesting the revised plan Schwarzenegger put out Wednesday, it’s too soon to tell whether the 2008 budget smackdown will match the bitterness of 1992-when the immoveable object of Republican Governor Pete Wilson met the irresistible force of Democratic Speaker Willie Brown, producing the summer spectacle of California paying its bills with IOUs-or of 2002, when the long fight led to the recall of Governor Gray Davis.

Capitol handicappers cite three key political factors that will shape this year’s fight, for better or for worse:

New Leaders: Two new, nonbattle-tested legislative leaders will join the Big Five talks, the closed-door negotiations where the budget deal, if any, goes down among and between the governor and the top dogs from each party in each house. Sworn in this week as the new Speaker of the Assembly is Karen Bass, the first African-American woman to hold the post. Bass (D-L.A.) has a reputation as a pragmatist and will look for a solution that combines tax increases and spending cuts. By contrast, Senate Republican leader Dave Cogdill of Modesto has quickly staked out an ideological line in the sand, telling the Sacramento Bee, raising taxes “makes absolutely no sense.”

Bright Ideas: A centerpiece of Schwarzenegger’s revised budget is a plan to leverage revenue from the California Lottery, both to help ease current fiscal woes and to establish a rainy-day fund to help stabilize state finances. Under the proposal, which requires voter approval, California would raise billions through the sale of securities guaranteed by future lottery ticket sales.

The Bass-Cogdill dynamic reflects the broader partisan pattern of historic budget fights, which often have had the substance and subtlety of those old Miller Lite commercials: “Less cuts!” “No new taxes!” Lawmakers of both parties previewed some of the positions likely to gain attention in the weeks or months to come.

Democrats are eyeing taxes on consumer services, from dry cleaning to Internet downloads, including “adult entertainment.” They also started airing an ad on Sacramento cable TV attacking the GOP for its refusal to close a loophole permitting buyers of expensive yachts to avoid sales tax by docking in Mexico or other foreign ports for 90 days after purchase.

Republicans have focused on economic stimulus plans for the private sector and money saving ideas, like bypassing requirements for union labor in school districts. Cogdill has a controversial proposal to borrow unspent money from special accounts designated specifically for transportation, mental health services, and early childhood education-each an earmarked program previously approved by voters.

Cash shortage: If the budget fight drags on, state taxpayers could pay a premium. With the state likely to run out of cash in late summer, the administration is expected to take a $9 billion line of credit; if California doesn’t have a budget plan in place, the fees and interest costs of borrowing would soar. “This is the worst I’ve seen,” Assemblymember Pedro Nava (D-Santa Barbara) said of the budget mess. “This is nothing that is going to be resolved easily.”

Among the toughest issues in the budget debate is funding for education, with California now ranked 47th among states in money aimed at public schools. “Political leaders all campaign in favor of education,” said S.B. County Schools Superintendent Bill Cirone. “And yet we’re a disgrace in terms of our investment in human capital.” Cirone, among the more outspoken figures in the state challenging the governor on the issue, added, “All we’re talking about is how do we put our finger in the dike,” as the state lurches from one budget fight to the next. What’s needed, he said, is “true structural reform [that] looks at all the sacred cows,” including Proposition 13.

Watch out for Howard Jarvis on that one.