E-Voting Made Scary

UCSB's Giovanni Vigna Gives Timely Talk on Why Electronic Voting Is Frighteningly Insecure

With the big ballot showdown on November 4 looming, a few dozen people on the UC Santa Barbara campus spent their Thursday, October 23, lunch hour digesting some pretty frightening news: Electronic voting machines – the officially appointed wave of our democratic future, being touted as safe, sane, and secure – are entirely vulnerable to election-altering attacks, ranging from the highly technical to the surprisingly simple.

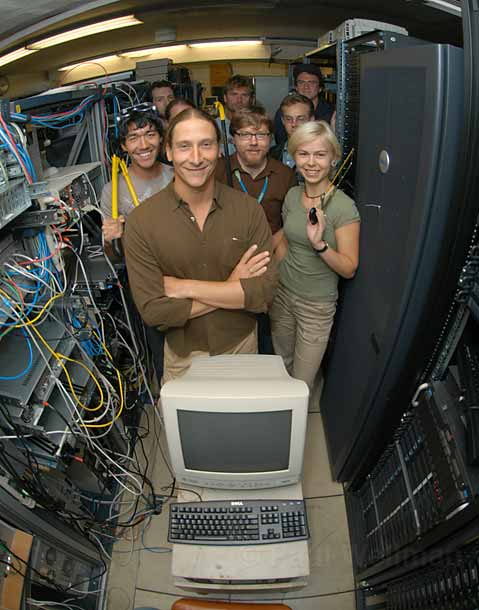

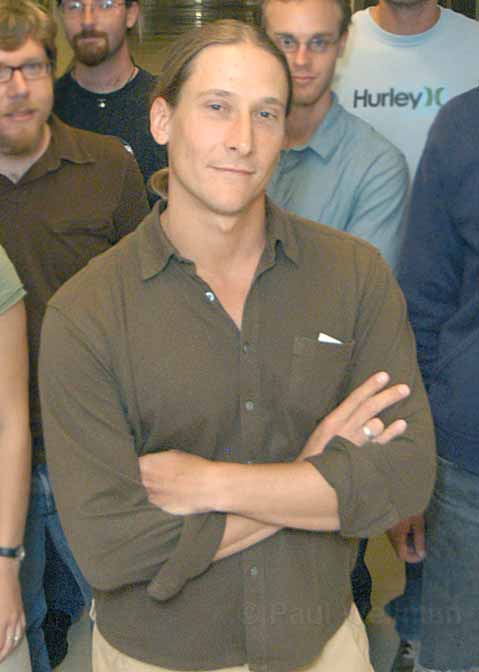

The messenger of doom was Giovanni Vigna, the golden-locked, Italian-born professor who runs UCSB’s Computer Security Group, which is considered one of the best places on the planet to learn about programming and hacking. Vigna, along with his mentor Dick Kemmerer and a team of sharp students, were hired in 2007 by the states of California and Ohio to test the security of electronic voting machines. In both cases, the machines – specifically, made by Sequoia Voting Systems in California and ES&S in Ohio – failed to stand up to even the most basic physical breaches, such as the unlocking of supposedly secure doors by using a screwdriver and a finger. The vulnerabilities witnessed from the computer hacking side were even more startling, showing that just one corrupt voting official or poll worker could, with the right amount of motivation, infect a state’s entire voting system within seconds by introducing a specially crafted computer virus to entirely change an election’s result.

Though the results of 2007’s tests came out last year, Vigna’s work has received a recent boost in buzz, certainly because of the upcoming election, but also due to YouTube videos of the simulated attack methods that went viral. (See those videos here, or just watch them on this page below.) And with reports this week of election machines in two states flipping early voters’ choices for president – Barack Obama votes were being cast for John McCain in West Virginia, with the opposite happening in Tennessee – Vigna’s talk on Thursday was right on time.

“Outsourcing the people who count your votes is not, in my opinion, a good idea,” Vigna told the crowd. “At this point, all bets are off.”

Vigna’s research has not uncovered any record of bias for one party or the other, just negligence. He believes that the machines were made hastily to get under a deadline imposed by the Help America Vote Act of 2002, which sought to improve voting machine reliability after thousands of electronic votes were discounted in the 2000 election. But because they were made so fast, not enough care was taken to ensure complete security, which is why there are so many ways to physically attack the system. “It’s really a problem keeping these things physically secure,” said Vigna, adding that the most important data-holding devices have to pass through many hands, thereby multiplying the chances for someone to act maliciously. As well, Vigna said, oftentimes these machines are housed overnight in the garages of poll workers, which aren’t necessarily the safest places to be.

But more troubling are the security holes in the computer programming, which are somewhat understandable, because cryptography is a very difficult thing to do correctly, admitted Vigna. He explained that the companies did technically encrypt the data, but then put the encryption key adjacent to the lock, which is analogous to having a safe full of money locked with the combination written outside the door on a Post-It note. He said machines also could be switched easily from test to election mode, thereby fooling honest attempts to assure they worked. And with just one slip of a USB drive into a single machine, the entire system can be corrupted, making the task very easy.

“[The presidential candidates] could stop spending money on their campaigns and give $20 million to one dude,” joked Vigna to the anxious laughter of the concerned crowd. “They could buy the election.”

Basically, Vigna believes that the taxpayers got a raw deal because the machines were so hurried. Although the companies were promising Ferraris, Vigna said, “We bought Pintos.”

He much prefers paper voting, because of the recorded history it leaves. “I know it’s expensive, but this is the most important step in the democratic process,” he said. “This country is outsourcing that step to companies whose goal is not necessarily being accurate. Their goal is making money.”

Though he doesn’t think electronic voting can be flawless unless everyone from programmers to poll workers have a degree in computer science, Vigna does believe that nationalizing the electronic voting machines would be better. And paper trails, even though they too can be corrupted, should be mandatory. Vigna realizes such reforms won’t happen by November 4, but said, “Maybe we have enough momentum to make a change four years from now.”