New ‘La Entrada’ Plans Unveiled

It's Back!

The bottom two blocks of lower State Street have been a festering construction site for so long that even city planners assigned to focus on the area can’t remember when it’s been otherwise. Ten years ago, this stretch of real estate seemed destined to become upscale Ritz-Carlton time-share condos known as La Entrada. But that scheme-approved by the City Council and Coastal Commission-burst as developer Bill Levy was forced to declare bankruptcy in 2006. Two weeks ago, the bankers who foreclosed on Levy, Mountain Funding, submitted revised plans for City Hall’s approval. Mountain Funding officials insist the new plans could be built, because unlike Levy’s proposal, they make financial sense even in today’s real estate market: In place of 62 time-share condos would be 114 hotel rooms and seven time-shares.

The bed taxes offered by the hotel rooms make the new deal more lucrative for cash-strapped Santa Barbara. And by building the main parking garage underground, they’ve been able to chop one story off the height of everything but the California Hotel, which will remain at its current 60-foot height. This, they contend, will be kinder to the mountain views than previous plans.

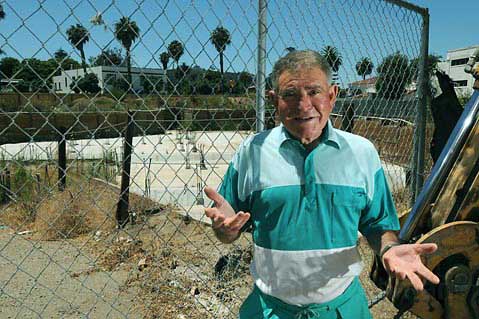

The $120 million question is whether the new plans “substantially conform” to the plans approved by the City Council back in 2001. If not, the project is dead in the water. The authority to make this decision lies with just one man: city planning czar Paul Casey. Already Casey and several city councilmembers have been barraged by a blistering campaign from Tony Romasanta, who owns the adjoining Harbor View Hotel. Romasanta contends City Hall should pull the plug on La Entrada and execute what he calls “a clean kill” on what he terms “a black hole.” Romasanta charged that Casey and the City Council have allowed Levy and Mountain Funding foot-dragging maneuvers under the pretext of securing financing and keeping permits alive past their expiration dates. But financing will never arrive, Romasanta asserted, because the project is so encumbered by debt that it can’t be financially viable. Meanwhile, he complained, one of the most-visited parts of town exists in a state of blight.

(Technically and legally, there is no debt on the project. When Levy declared bankruptcy in 2006 and his lender Mountain Funding took over the project, the bankruptcy judge recognized the $30 million that Levy owed them as Mountain Funding’s “payment.” On the books, that wiped the slate clean. But as a practical matter Mountain Funding has sought to recoup much of that lost $30 million when structuring deals with prospective investors and partners. That “ghost debt” has haunted such negotiations and to date, no deal has been consumated.)

This is not the first time Romasanta has gone on such a rampage, just the most intense. Among other things, he’s now demanding that Casey be fired. By yanking the permits that have kept the project artificially alive, Romasanta projected the value of the hole in the ground by State and Mason streets will plummet. City Hall could buy the land cheaply and create a municipal parking lot big enough to service the train depot for when commuter rail becomes a reality.

Casey said he understands exasperation over the delays, but cautioned that he can’t order banks or investors in the project to bring it to life. Even facing down the wrath of Romasanta, Casey has maintained a sense of humor, refusing to call the excavation site a hole. “I prefer to call it a ‘depression’ of sorts, an ‘excavation,'” he said. Casey declined to discuss Romasanta’s objectives, suggesting both he and City Hall could be sued for what’s known as “inverse condemnation” if he did. Casey acknowledged he probably has the legal grounds to pull the plug on Mountain Funding and withstand any legal challenge. “It’s a discretionary call,” he said. “The real question is ‘What’s good enough?’ And I don’t know.”

For the time being, Mountain Funding -which has yet to demonstrate it’s able to deliver on the latest plans-is hoping that the “guaranteed” promise of a completed parking garage might be enough. Casey is not sure that would be sufficient or how such a guarantee might be enforced. It’s been 10 years since the original La Entrada plans were first approved, so Casey feels comfortable taking time to decide. He plans to submit the revised designs to the Planning Commission in September, then, and after hearing the commissioners’ recommendations, decide.