Our Comrade in Cuba

One Educator's Descent into Socialism

I arrived at the Casa de Jorge after a very dark ride through Havana, ending in a pitch black alley close to midnight. Outside my cab was the head of a chicken detached from its body. Jorge called me up from his third story balcony, and I wrestled my luggage up his crumbled and uncomfortably narrow stairwell. He welcomed me into his home, speaking Spanish at a speed I thought was impossible to articulate, let alone understand. It was a humbling experience to be warmly welcomed as a stranger into Jorge’s home, while his mother was fast asleep in the next room. Jorge gave me a brief introduction to La Havana Vieja, and to the rules of casas particulares (Cuban homes available for travelers), and said goodnight to his bedraggled guest. I took the first of many cold Cuban showers, and passed out.

The Forbidden Threshold

It was on a trip back from Costa Rica last summer that I first began to wonder how I might go about gaining legal access into the closest communist hotbed to the United States. My mind began to race as I pondered a country that I was not allowed to visit.

Sorting through all of the political red tape, I found that Americans can actually fly to Cuba legally as long as they book their flight to Havana in a third country (e.g., Canada, Mexico, Jamaica, etc). However, Americans are not allowed to spend money in Cuba. If you do spend money there, you are in violation of the Trading with the Enemy Act. Nice catch. You also are at risk of penalty if you lie to a federal customs agent about your recent travel whereabouts once back in the U.S.

Americans can apply to the U.S. Department of the Treasury for specific licenses to Cuba, but these licenses are rarely granted. My last sliver of hope came from a charter company in New Jersey, Marazul Charters Inc. Through Marazul, I found that I qualified under what is called a general license. I had to show proof that I was a full-time professional, traveling for research related to my field. In my case, I wanted to see how people with special needs were included in families, schools, communities, and the workplace. I became interested in inclusion as a result of seeing the benefits of it with my own students at Kellogg School in Goleta, and in 2003 had joined CalTASH, an organization dedicated to giving equal access to all facets of life for people with significant special needs. Once I sent in my paperwork, I awaited a response with my fingers crossed.

In the interim, I began setting up contacts in Cuba, and came across the Cuban American Alliance Education Fund (CAAEF), and its president, Dr. Delvis Fernandez. Through Fernandez and his Cuban contacts, I was in touch with the Asociaci³n Cubana de Limitados F-sico Motores (ACLIFIM), a grassroots organization that advocates for health, education, community inclusion, and general rights of people with various physical disabilities.

Collecting Commie Cash: I departed from LAX on the night my school let out for winter break. I had the normal pre-travel jitters, but my Cuban destination added a bit more stress to my winter holiday. Since the U.S. dollar (USD) is not accepted, at least not legally, in Cuba, and ATMs and banks do not accept U.S. ATM cards, I had to carry all of my spending cash with me. I also had to exchange my money into Euros in Cancun, and then into Cuban convertibles once I reached Havana. A Cuban convertible (CUC) is one of two currencies in Cuba. CUCs are for tourists, while the Cuban peso (CUP) which is worth close to nothing is for Cubans. Cubans earn about 530 CUP a month, roughly the equivalent of $20 USD.

Rolling Antiques: In the morning, Jorge’s mother prepared for me a breakfast of fried eggs, bread, and strong Cuban coffee. As I finished breakfast and soaked in the view from the balcony, I was in awe at the beauty of the crumbling city before me. Shutters were unhinged or missing, balconies were clinging precariously to buildings, and women were gossiping while hanging their laundry out to dry. It was as if time had stood still since the U.S. Embargo in 1962. I had a stunning view of the Malec³n, Cuba’s most famous sea-swept street, running along the northwest coast of Havana, where old classic cars rumbled along and spewed fumes into the atmosphere. Gazing at the sea beyond the Malec³n, I realized that boats were strangely absent from this quintessential Cuban scene. This was especially strange as I was visiting from the boat-filled seascapes of Santa Barbara. I later learned that Cubans are not allowed to own boats, as they could be used as escape vessels to the U.S.

Later that morning I set off in search of the ACLIFIM office. I asked what seemed like a million people for directions, but received no pushes in the right direction. Feeling a bit anxious about not meeting up with my contact at ACLIFIM, I set out on foot to explore Havana to see if I could check out some schools, or connect with people plugged into the disability community. I was immediately distracted by the plethora of antiques on wheels all around me. Being in Havana was like walking through a living museum.

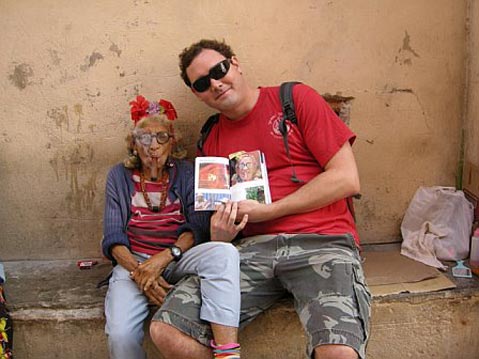

As I wandered down the weathered, forbidden streets, I came across historic churches, Cubans hawking authentic Cohiba cigars, and La Bodeguita del Medio, a bar Ernest Hemingway made famous and where he allegedly invented the mojito. Hemingway traveled to Cuba in 1928, and again in 1932, staying there until 1960, writing some of his most famous books there. I also noticed a very high number of people with physical disabilities using wheelchairs on the cobbled streets. Though people with physical impairments seemed to have access to wheelchairs, I saw a lot of debris on the streets, missing manhole covers, and a lack of curb cuts at intersections. From my observations, this made navigating Havana, for a person with disabilities, quite treacherous.

After sampling some spirits with the locals, on the Malec³n during an unforgettable sunset, I set out to find my way back to my casa particular. Along the way I ran into Cira, a Cuban woman I met randomly on the street, who happened to be a special education teacher in Havana Vieja. She teaches at an escuela especial, for students with emotional and behavioral disabilities. She said her students used to attend typical schools, but were placed in a special school because their behaviors were too disruptive in their former setting. It was easy for me to pass judgment on the Cuban schools system for sweeping the students with disabilities out of sight, but this type of restrictive and segregated school placement is not abnormal practice in the United States either. For every depressed facet of Cuban life I witnessed, there seemed to be a comparable American counterpart (think Flint, Michigan, in the tropics). The more of Cuba I experienced, the more parallels I found to my own country. Seeing so many challenging aspects of daily Cuban life made me choose to view Cuba as a place of opportunity and growth.

Good People and Good Rum: Along my journey through Cuba, one thing consistently amazed me: The people are always friendly. Once I became used to asking Cubans to speak slowly, I found most of them eager to talk about Obama, about the embargo, and how they have hope for a different and free Cuba. Only once was a negative word uttered about the Castro brothers. The young couple I was speaking with explained that all criticisms of the totalitarian Castro regime had to be discussed alone, and outdoors, or one was at risk of being turned in for personal gain by an eavesdropping neighbor.

Even though the people were amazingly open and warm to me everywhere I went, there was still something just under the surface I knew I was not privy to. There was a sadness to them that was overwhelming. I was lucky enough to have met a family in Santiago de Cuba who invited me into their home for Christmas Eve dinner. The night was nothing short of amazing even though they had very little to offer in terms of amenities in their home (concrete slab, bare walls, propane tank stove, no running water). We had fried fish, a local beer, a mixture of wine and rum, a smorgasbord of tasty local appetizers, and an amazing set of Cuban music. I learned that Auntie Sonia was a teacher at a special school for children with hearing impairment and deafness, and she said she would be interested in collaborating with me, and in learning more about inclusion. I departed from my Cuban hosts with a camera full of rum-fuzzed photographs, squeezed my fat noggin into a motorcycle helmet, and caught a ride home from Aunt Sonia’s boyfriend in the sidecar of his motorcycle.

Higher Learning: What I witnessed in the schools I visited was quite different than what I expected from a country that appears to be overwhelmingly destitute upon first glance. The schools I visited throughout Cuba were crumbling just like a majority of the buildings in the country, but they were far from eroded on the inside. The halls were full of clean, uniformed, and vibrant students. There was a definite air of authority and strictness in the schools. Though in major need of a facelift, the Cuban schools are attuned to produce a 99.8% adult literacy rate compared to the 92.4% adult literacy rate produced by the United States. (What Cubans are allowed to do with their literacy is a completely separate issue.)

In any case, this Cuban literacy statistic and my experiences developing inclusive practices in California contributed to my hopeful feeling that there are things Cuba and the United States can learn from one another. I saw a huge number of escuelas especiales where kids with a multitude of disabilities were educated. I came across schools for people with blindness, deafness, autism, emotional and behavioral challenges, and schools for people with physical impairments. While this is not an inclusive model of education, I was pleasantly surprised that students with disabilities were expected to attend school, and eventually work in their communities once they reach adulthood. This is a far cry from other developing countries I have visited, in the Middle East and South East Asia, where people with special needs are not always expected to contribute to society in ways they can.

Although I gathered enough information about the educational and medical care provided for Cubans with disabilities through casual conversation, I felt it necessary to speak with a professional. For this, I called the only Cuban I knew who spoke English fluently, Dr. Delvis Fernandez.

Seeing Beyond the Rubble: Dr. Fernandez was born in 1940 in Santa Clara, Cuba, a city which would later come to be known, starting in 1958, as the place where Che Guevara coordinated a fatal blow to the Batista regime, and made revolutionary history. Fernandez was one of eleven students to graduate in 1957 from the only public high school in Santa Clara, out of a class of more than 600 students, in the midst of bombings, riots, and strikes. After graduating he caught a flight from Havana to Key West for $11, on the tab of a rich uncle, in order to pursue a better life in the U.S. Once in Florida, he caught a bus to Utah with the $50 he’d saved in Santa Clara and kept in his pocket.

After hearing about his impressive accumulation of degrees and accomplishments, I noticed that Dr. Fernandez did not mention Cubans with disabilities. When asked how he came to be involved with the disability movement in Cuba, he told me the story of his ailing sister in Cuba, and how he was not allowed to visit her when she was ill in 1994. This prompted him to bring the human side of the Cuban-American embargo to the halls of Washington D.C. Dr. Fernandez put a face to people in Cuba suffering with disabilities. He brought Cubans with special needs to meet President Clinton, and to speak in the Pentagon, the Senate, and in Geneva at a human rights commission regarding lives upset by Cuban-American regulations. When asked about any other personal experience with disability in Cuba, Dr. Fernandez explained the impact his father’s leg amputation, and cousin’s disability from a bus accident, had on his family. These experiences in Cuba, coupled with the illness of his sister, ultimately led him to work closely with ACLIFIM starting in 1996.

Through ACLIFIM, Dr. Fernandez was able to work among Cuban families who had loved ones with disabilities. In Cuba, he witnessed a rehabilitation program for preschool-aged children with disabilities, and found that parent participation was an integral and involved aspect of the program. Not only are parents engaged in these types of support services, but extended family, friends, and neighbors often gather together to support the loved one in the home setting.

I asked Dr. Fernandez if this type of collective support extended to people with disabilities in the workplace, and he said it was not uncommon for people with disabilities to organize and run programs while managing their “neurotypical” counterparts. We went on to speak about the crumbling buildings and deteriorating streets throughout Cuba, and how there is a huge lack of accessibility to public venues throughout the country. This lack of community accessibility is one of the biggest focuses of ACLIFIM advocacy in Cuba.

Our Enemies: While in Cuba, I was often in awe at the hospitality of the people, and the beauty of the country. I was intoxicated by the music, culture, and vibe of the country. I was inspired by the unapologetic means by which the Cuban people scraped by with what little they had. I was also deeply saddened by an unhappiness that seemed to rest just beneath the surface of the Cubans I met. Many expressed to me that they felt trapped in a country they loved. They were proud of their culture and education, but yearned to share it with the rest of the world. I learned a tremendous amount about Cuban life in the short time I was there, from citizens of a country that is close in proximity, but worlds apart. When I landed in Cuba I was sure of the knowledge and experience I could impart to the people involved with disability there. What I actually learned from them is that we have much to realize in the United States about how we view and support people with special needs. Perhaps a country labeled “communist” has more to offer the world than a label.