Courts to Stem Funding?

UCSB Scientists Fret Over Future of Embryonic Stem Cell Research

Dr. Norbert Reich, a chemist and stem cell researcher at UCSB, received good news in August. He learned that a proposal he had sent in to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for a research grant had garnered excellent scores from a peer review. That means a committee of medical health scientists deemed his project worthy of funding. But it is now almost November and he has not received his funding.

Reich believes that the hold is due to the Sherley v. Sebelius court case in which two plaintiffs, Drs. James Sherley and Theresa Dreisher, are seeking a ban on federal funding for human embryonic stem cell (hESC) research. These two scientists oppose the research on moral grounds, and furthermore argue that funding for it diverts funding from viable research on adult stem cells — exactly the sort of research they are engaged in. Their claim that they are harmed by federal funding policies is what legitimizes their court case.

On August 23, soon after Reich received his score report, Judge Royce C. Lamberth of the District Court for the District of Columbia, sided with the plaintiffs. He ruled that hESC research violates the Dickey-Wicker Amendment, a rider that has been attached to all health appropriations bills since 1996. The amendment prohibits the use of federal funds for “(1) the creation of a human embryo or embryos for research purposes; or (2) research in which a human embryo or embryos are destroyed, discarded, or knowingly subjected to risk of injury or death greater than that allowed for research on fetuses in utero.”

The decision by Lamberth, a Reagan appointee, took scientists by surprise. Michael Witherell, Vice Chancellor for Research at UCSB, said the ruling “sent a shockwave through the scientific community.”

Dennis O. Clegg, co-director of UCSB’s Center for Stem Cell Biology and Engineering, does not have much sympathy for the plaintiffs. “Grants should be based on the merit of the science. I think it’s a weak argument,” he said. Clegg also disagrees with the case on moral grounds. “I feel there is a moral imperative to do this research because there is a tremendous capacity to end the suffering of people with illnesses,” he said. Clegg added that the potential cure to a disease would result in the destruction of only a single embryo.

The U.S. Court of Appeals in Washington, D.C. has since decided to hear the case and, on September 9, lifted the injunction on federal funding for embryonic stem cell research, at least until it makes a decision. The lift allows ongoing research to continue uninterrupted for the time being.

There is no clear evidence that the court case is holding up Reich’s funding, which he said will support the salaries of five or six lab workers. But he still suspects that may be the case. Publicly, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has protested the District Court ruling. In a press conference following the decision, NIH Director Francis Collins said, “Stem-cell research offers true potential for scientific discovery, and hope for families. This decision has just poured sand into that engine of discovery.” Reich agrees that the NIH staff is “as bent out of shape as I am,” about the ruling. Still, he isn’t sure that the lifting of the injunction has persuaded the agency to set new projects in motion.

Reich’s case is unusual because currently, most stem cell research at UCSB is funded by the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM), an entity established in response to President Bush’s 2001 executive order banning federal funding for research on stem cell lines beyond the 60 in existence at the time. California voters approved the establishment of CIRM when they voted to pass Proposition 71 in 2004, making California “a mecca for stem cell research” according to Clegg. Through June 22, 2010, CIRM had provided California institutions with over $1 billion in funding, $8,616,459 of which has been granted to UCSB for training, research and facilities. CIRM is funded by the sale of bonds.

Still, CIRM does not fund a hundred percent of the research on campus and Witherell said that should the Sherley decision be upheld, the university will need to solicit private funds to make up the difference. Moreover, NIH grants, aside from money, provide the intangible resource of prestige.

Sherry Hikita, director of the Lab for Stem Cell Research at UCSB, said that all of her research is funded by CIRM. Nonetheless, she said that the federal court case “may have significant consequences for my future work with human embryonic stem cells.” Hikita also worries that a lack of federal funding—which is acquired through an anonymous process—will hurt younger researchers who can’t yet rely on the weight of their reputation to solicit alternative sources of funding.

On September 20, the University of California filed a motion to intervene in the Sherley v. Sebelius case. An accompanying statement reads, “The University takes this step [to file a motion] in order to directly weigh in with the court regarding the harm to research institutions engaged in this critical research that will result from a suspension or termination of access to federal funds. The University of California believes it is imperative that the scientific community be permitted to move forward with embryonic stem cell research that provides hope to millions of patients and their families.” In addition, Dr. Arnold Kriegstein, MD, PhD, and director of the Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regeneration Medicine and Stem Cell Research at UC San Francisco, filed a declaration in support of the motion.

Typically universities rely on research consortiums with staffs in Washington D.C. (such as the Association of American Universities and the Council on Governmental Relations) to advocate on behalf of the interests of universities. The UC Regents, however, decided tjat as the nation’s largest public university system, the UC should take a stand of its own, said Witherell.

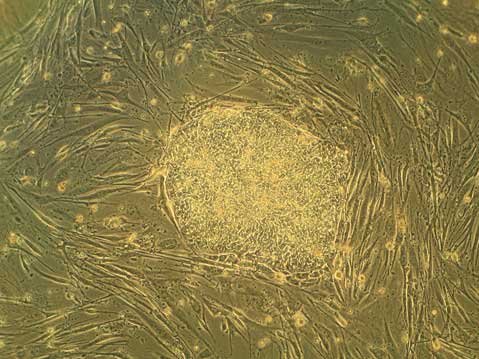

The Ethics: A stem cell line is a batch of stem cells that have successfully replicated over time without forming genetic abnormalities. Millions of cells can be generated from a single line and batches of these cells can be frozen and transported to different laboratories.

Human embryonic stem cell lines are generated with embryos that have been fertilized in in-vitro fertilization clinics. Many people, including pro-lifers and members of some religious organizations, believe that a fertilized embryo constitutes a human life and tampering with one, even if it was never incubated, is tantamount to murder.

On March 9, 2009, President Obama issued an executive order rolling back President Bush’s limits on stem cell research. Judge Lamberth’s decision does not merely return to the Bush-era funding regulations. They are even more stringent: Lamberth wrote in his decision that any stem cell research necessitates the destruction of embryos.

Dr. Erikki Ruoslahti, a cancer researcher at UCSB, said that “ultimately it is the patient who suffers” when hESC funding is prohibited. He believes that the issue will not be resolved until Congress acts.

Robert Lanza of Advanced Cell Technology in Worcester, Massachussetts has pioneered a technique for beginning an embryonic cell line by extracting a single cell from an embryo, leaving the embryo unharmed and intact. He demonstrated this technique with mouse cells and reported his findings to great fanfare in a 2006 issue of Nature. Even if Lanza’s results could be consistently reproduced with hESCs, Ruoslahti believes, research done with the resultant stem cells would still be opposed by right-to-lifers. “The whole idea of them being embryonic has become toxic. [The opposition is] no longer rational.”

The Research: Judge Lamerth conjectured in his ruling that “the harm to individuals who suffer from diseases that one day may be treatable as a result of ESC research is speculative. It is not certain whether ESC research will result in new and successful treatments for diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease.”

While researchers concur that media portrayals of stem cells as a possible miracle cure for an untold number of diseases sometimes run ahead of what responsible scientists can currently claim, they are palpably excited about the possibilities of stem cell therapies.

Before hESCs are applied to therapies, though, scientists still need to figure out exactly how they work. The crucial difference between adult stem cells and hESCs is that the former are more tailored towards specific purposes while the latter readily develop into any adult cell type. (There are over 200 in the human body.) This embryonic process is called differentiation.

This is where Reich’s work plays a role. Reich has designed a technique for demonstrating exactly how hESCs differentiate. He has invented a method of inducing a cell to accept a foreign material by stimulating it with light. The foreign material he wishes to introduce to hESCs is RNA, a close relative to DNA, and a sort of messenger which carries DNA’s instructions to the rest of a cell. Specific genes in a cell can be turned off when RNA is introduced to them. After introducing RNA to an hESC on a gold particle, Reich hits the cell with a laser beam which both releases the RNA from the gold particle and induces the cell to accept it. By turning off specific genes, scientists can discern what role those genes play, if any, in the process of differentiation.

As Reich explains it, stem cells are like parts of a tree and hESCs are the trunk. “The further you go out on the branches, the further committed you are to a specific role. . . How do you delineate,” he asks, “the factors that make one branch go left and another go right?” His goal is to understand that process.

According to Witherell, Reich’s project is slated for an April start date, presuming the funding is in place. Meanwhile, UCSB is planning to add 10,000 square feet of facilities for stem cell research in the Biosciences II building on campus. Whether it can afford enough research to fill the space is another question.