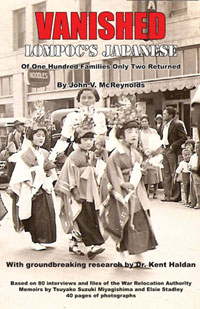

Vanished: Lompoc’s Japanese

Japanese Internment Is Explored in a New Book by S.B. Author John McReynolds

The attack on Pearl Harbor and the outbreak of World War II provided a golden opportunity for unscrupulous farmers throughout coastal California to fan racial fears about Japanese agriculturists, wipe out the competition, and reap the sort of whirlwind profits that only wartime shortages can generate.

In the book Vanished, John McReynolds’s emotionally moving and historically complex examination of how Lompoc’s first- and second-generation Japanese immigrants fared during this period, the bad guy is clearly Tom Parks, a onetime mule driver with a 7th-grade education who arrived in Lompoc in 1928 to plant vegetables.

Crude, shrewd, loyal, and overbearing, Parks was one of the few Caucasian growers to compete directly with the Issei and Nisei for the lucrative vegetable produce market that they largely had pioneered. Even before the war, Parks had distinguished himself with organizations that had lobbied for laws to make it harder for Japanese farmers to even rent land. (They’d been barred from direct ownership since 1913.)

Beginning in 1940, Parks also played a key role in the formation of the local Home Guard within the American Legion, designed to ferret out possible saboteurs and fifth-columnists before they could strike. Initially, Santa Barbara District Attorney Percy Heckendorf, a close confidante of Governor Earl Warren, worried that Parks’s Home Guard had vigilante tendencies and cautioned against “witch hunts and wild goose chases.” But after Pearl Harbor, Heckendorf changed his tune. And when a Japanese sub shelled the Ellwood oil fields a few weeks later, Heckendorf became more insistent the Japanese must be removed from the coast.

Until then, McReynolds writes, Lompoc had enjoyed a 20-year period of racial tolerance and cooperation. One of the strengths of this book is McReynolds’s description of how Japanese immigrants made Lompoc their home. They had their own sports leagues, religious communities, and business associations, but they joined in with those of the greater community, as well.

Eventually, 100 families would be forced out of Lompoc after President Franklin Roosevelt signed the executive order to round up all the Japanese—native born American citizens and immigrants alike—living along the coast and place them in internment camps. Parks and Lompoc’s Home Guard provided the basic blueprint not just for Heckendorf in Santa Barbara County but also for Governor Earl Warren and all the counties in the state. Even after the war, Parks would lobby against the return of the Japanese from the camps.

In places, McReynolds’s writing could be smoother. But he’s brought considerable new research, melded it with files from the War Relocation Authority, and taken full advantage of existing scholarship to create a fresh look at an old human rights controversy that, despite the passage of time and lessons allegedly learned, remains painfully contemporary.